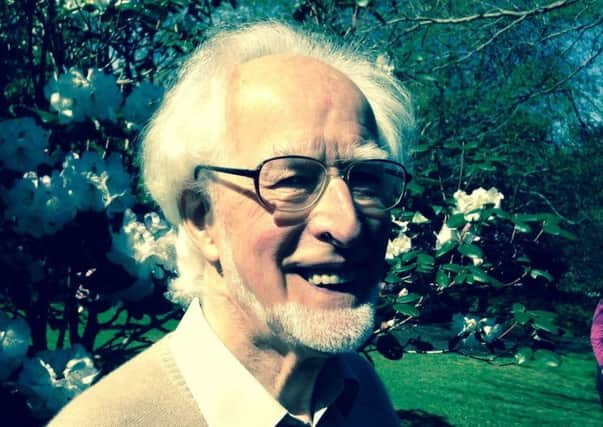

Obituary: Rev Andrew Morton, minister and teacher

The Rev Andrew Morton was an outstanding leader of his generation of Church of Scotland ministers, a passionate socialist and internationalist who worked tirelessly throughout his life for the causes of social justice, democracy, human rights and church unity, but also made time – alongside his late wife Marion Morton, a former deputy lord provost of Edinburgh – for an exceptionally rich and fulfilling family life, and for many profound life-long friendships, both in Scotland, and far beyond.

Andrew Reyburn Morton was born in Kilmarnock in 1928, the son of a clerk at the local engineering works who suffered from ill health after serving in the trenches during the First World War, and of a former seamstress who – after her husband’s untimely death in 1932 – took in lodgers to make ends meet. Despite the loss of his father, Andrew Morton had a happy childhood, presided over by his mother, his grandparents, his older sister, Nan, and his brother, Tom, 13 years his senior. Both Andrew and Tom – later the minister of Stonelaw Parish Church in Glasgow – were regarded as exceptionally bright scholars from an early age.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAndrew won the rare accolade of being literary dux of Kilmarnock Academy in both 1944 and 1945, and went to Glasgow University to study Greek and philosophy, a subject he loved – but he was already strongly involved in the radical Christian movements of the time, and with organisations including the recently-founded Iona Community, and the Student Christian Movement.

After he graduated, he moved on to study theology at New College in Edinburgh, graduating in 1952, and also winning a World Council of Churches scholarship to study abroad for a year. It was in Germany that summer that Andrew first met Marion Chadwin, whose aunt, Euphemia Abbott, was running Church of Scotland canteens for the British Army on the Rhine. After working together for several years for the SCM in Glasgow, the couple eventually married in 1958, when Andrew had become a parish minister in East Kilbride.

Between 1960 and 1966 the couple had four children, Maddy, Mike, Chris and Julie. In 1964 Andrew was delighted to be invited – despite his relative youth – to become Chaplain at Edinburgh University. The family took up residence in the chaplaincy at 21 George Square, where Andrew and Marion cleared out the basement to create 21 Down, a kind of always-open coffee lounge for any student who wanted to drop in and talk about ideas or religion or politics. Their daughter Maddy remembers a strong Sixties atmosphere of international debate, openness to new and radical ideas, music, poetry, and late-night discussion.

In 1974, after a period at Wolfson Hall, Glasgow University, the Mortons moved to London, where Andrew became Secretary for Social Responsibility at the British Council of Churches. Andrew and Marion were always staunch members of the Labour Party, and Andrew stood for election to Lambeth Council – on the strict understanding that he would probably lose.

In 1981, the call came for Andrew to return to his beloved Edinburgh, and to the Church of Scotland offices at 121 George Street, to begin the job that would take him through to formal retirement age, as the church’s Secretary for Ecumenical and European Affairs.

These were momentous years in international politics and in the politics of religion, as the grip of communism on Eastern Europe began to weaken, and countries like China began to open up to the West; and Andrew’s combination of intellectual openness, strong emotional empathy, and unfailing commitment to the cause of human dignity and equality made him an outstanding figure in the civic politics of the time, both internationally and in Scotland.

In the 1980s, he was part of the first-ever delegation of international churchmen to visit communist China; and his passionate concern for the future of the peoples of Europe led not only to a period of intense travel and negotiation across the Continent, but also to his increasing involvement in UK movements such as Charter 88, which used the model of East European civic campaigning to work for constitutional reform in Britain, including Scottish home rule.

After his retirement from the Church of Scotland in 1993, he became associate director of the Centre for Theology and Public Issues at Edinburgh University, and was able to give more support to his wife Marion in her political life – she was elected an Edinburgh councillor in 1994, and served as deputy lord provost from 1999 to 2003. It wasn’t until 2011, when he was already well over 80, that Andrew Morton finally retired from his last university role, as New College’s alumni officer.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAndrew’s last years were shadowed by the loss of Marion, who died in September 2013; but even after he received his own terminal diagnosis last year, he remained – in the words of his friend, the Rev Hugh Davidson, at his funeral service in St Giles’ Cathedral – the same Andrew Morton: gracious, cheerful, positive, hospitable, curious, interested in his friends, and concerned about the wider world.

As his daughter Maddy said in her funeral address, he was a man of great faith and great democratic intellect, whose mind was always “as broad and open as a northern sky”. Yet he was also a man of great heart and happiness, survived by his four much-loved children, and seven grandchildren; and by a huge network of friends, colleagues and fellow campaigners whose lives were changed by his breadth of vision, his sympathetic sharpness of perception, and his gentle insistence that to work tirelessly for the freedom and dignity of others is not only an obligation, but a source of joy, and of the sense of a life well lived, to the end.