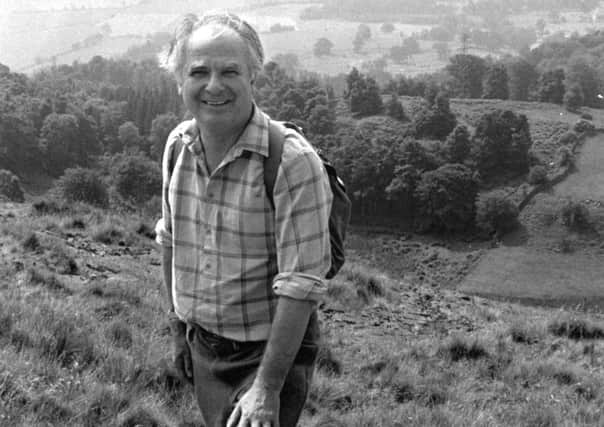

Obituary: Rennie McOwan, journalist and outdoorsman whose campaigning helped enshrine the right to roam

Rennie McOwan was an esteemed outdoorsman, journalist, writer and broadcaster who was steeped in the history, folklore and culture of his native Scotland. He was a man of conviction who was not afraid to push against the tide if he felt the cause was right. Brought up in a respectable Presbyterian family, he converted to Catholicism in his twenties, campaigned for an independent Scotland long before it became popular and for more than 15 years played a key role in persuading authorities to make freedom to roam in Scotland a legal right.

As a young boy, his parents gave him complete freedom to roam the Ochil Hills around the village of Menstrie near Stirling, where he was born in 1933. The hills, mountains, burns and braes became his playground, and fishing, birdwatching and swimming were second nature to him and his siblings. His great grandfather, Donald Ross, was a legendary chief stalker on the Duke of Portland’s estate in Caithness. The folk tales he would tell were handed down to the young Rennie, piquing his interest in his Gaelic heritage. His parents instilled in him the virtues not only of self-reliance but also egalitarianism. It was as a small boy that he first encountered a recalcitrant landowner who, on denying him access to his land, was met with the question “why can’t we go this way?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe used his journalistic skill later in life to campaign for responsible freedom to roam. He began as a trainee reporter on the now defunct Stirling Journal in 1953 after two years of National Service with the RAF in England. In 1956, he progressed to The Scotsman in Edinburgh, soon becoming Scottish Desk editor. Despite being a country lad, he relished life in the capital city with its jazz clubs and concerts at the Usher Hall. In 1957 he founded the Scotsman Mountaineering Club (now the Ptarmigan club) with Sir John Hunt, of Everest fame, as president.

It was in Edinburgh that a friend introduced him to his wife-to-be Agnes, a firm Catholic who impressed him with her conviction and the way she defended her faith. Agnes was a firm advocate of civil rights at a time when Catholics were discriminated against in such matters as housing and employment. The words “no Catholics need apply” were not uncommon in employment notices. At about the same time, he became friends with Fr Lawrence Glancy, an Oxford graduate and linguist who would remain a mentor for much of his life. They would meet regularly at St Peter’s Catholic Church in Morningside and engage in rigorous theological debate. Glancy sensed a vocation in his friend. In 1958 McOwan was received into the Catholic Church. He decided that Catholic journalism was to be his way forward.

In 1962, at the age of 29, he gained his first editorship, of the Scottish Catholic Observer, and succeeded in making it the voice of secular, modern Catholicism. One national daily declared his tenure as “a period of editorial brilliance”. The circulation grew rapidly, though McOwan put this down to its new sports section under former Scotland defender Willie Toner, whose brief had been “not just Celtic”.

He left the Observer for a four-year spell in Liverpool, editing The Universe. In 1968 McOwan beat more than 300 other applicants to become the first Communications Director for the Catholic Church in Scotland. He made the office a magnet for all media enquiries. The job was not without its challenges. In Rome, while handling the elevation of Archbishop Gordon Gray to Cardinal, the first Scottish Cardinal for 400 years, he discovered to his horror that all the Vatican press releases were written in Latin. A hasty summoning of a translator was required to subdue the English-speaking press corps.

On the same assignment, Pope Paul VI granted him an audience and was intrigued by a convert achieving this important position. During his tenure, McOwan forged closer links with other churches, and stressed the importance of dealing with the media to several organisations, including an assembly of the entire Catholic hierarchies of the UK countries.

Yet, he disagreed with the Vatican’s stance on birth control, and with sadness left the press office to join, first, the National Trust for Scotland, then, in 1978, the Edinburgh Evening News as senior features writer. But it was his decision to go freelance in 1982 that enabled him to write freely on issues about which he felt most passionate, such as Scottish Nationalism and the freedom to roam. The latter was an ancient de facto right which was in danger of being lost by default and therefore needed codifying.The issue had arisen again because of the surge in popularity of outdoor pursuits. It started as a lonely struggle for McOwan and other campaigners since many of the countryside organisations were wary about criticising the landowning fraternity with whom they had long-standing connections.

Gradually, his well-reasoned rationale and historical and cultural knowledge that he expounded in his newspaper columns and on TV helped the campaign turn the tide. His contribution to the access debate was recognised when, in 1996, he was invited to address the Landowners Federation on behalf of all Scotland’s outdoor groups at the launch of the Access Concordat. His address was described by the chair, Magnus Magnusson, as “statesman-like”. In 2003, The Land Reform Act (Scotland) enshrined freedom to roam in law.

McOwan was awarded the Outdoor Writers Guild Golden Eagle Award for access campaigning and contributions to Scottish culture and an honorary doctorate from Stirling University, also for his contributions to Scottish culture.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe would go on to become a regular writer and broadcaster on a variety of topics. He wrote the outline script for The Prince of Wales’s ITV Wilderness documentary and penned more than 15 books, many of them for children.

The last ten years of his life were ones of gradual declining health due to Parkinson’s disease.

Broadcaster Cameron McNeish said: “I have always been indebted to Rennie for so willingly and generously sharing his immense knowledge of Scottish mountaineering, history, folklore and culture.”

Archbishop Leo Cushley of St Andrews & Edinburgh added: “Many people knew and admired Rennie as a distinguished writer, broadcaster and outdoorsman, but he was also a great trailblazer in attempting to use modern communications at the service of the Church, both as Editor of the Scottish Catholic Observer and as the first Communications Director for the Catholic Church in Scotland.

Rennie McOwan is survived by Agnes, a daughter, three sons and five grandchildren.

bob CHAUNDY