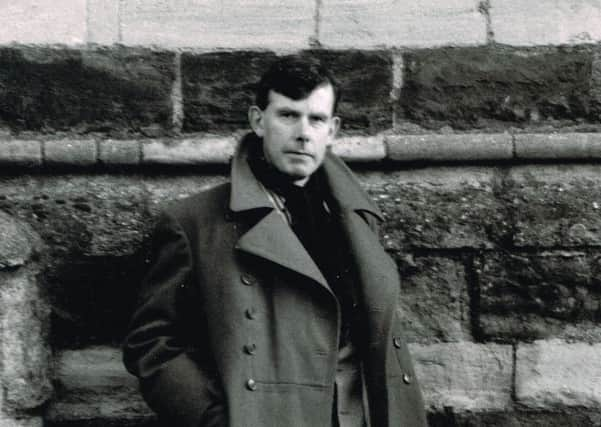

Obituary: Professor Gavin Stamp, Private Eye's Piloti and a tireless campaigner for preserving historic buildings

Erudite, entertaining, elegant, an outspoken maverick – Gavin Stamp was all of those and more: one of the original Young Fogeys, he was dauntless in preserving the past and defended architectural heritage with unwavering and utter conviction.

Having been proud to sport tweeds, a waistcoat and fob watch, he was not afraid to champion the unfashionable, resided at one time in the red light King’s Cross area of London and revived interest in the neglected Scottish architect Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA distinguished academic, historian, writer, conservationist and broadcaster he was born in Bromley but gravitated to Glasgow where he lectured at the Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow School of Art, living in a restored classical house designed by Thomson.

He had first visited the city in 1968, to see the world-renowned buildings created by Thomson and the architect, designer and artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh. He was not disappointed, he said, but he was dismayed by Glasgow seeming to “wipe itself out” through a programme of comprehensive redevelopment and road building: Mackintosh buildings were endangered and Thomson’s were tumbling.

He later declared: “It seems to me that Scotland is a country that has lost its way,” and confessed he had become a “romantic English Scottish Nationalist” arguing that if other small countries with “wild landscapes and awful weather, like Norway and Finland, can make a success of going it alone, why not Scotland?”

Stamp, who left Scotland to return to Cambridge where he had read history and then history of art at Gonville and Caius College, was educated at Dulwich College and joined the Victorian Society as a teenager, in response to the threat to London’s St Pancras Station.

For most of his career he was a freelance writer on the history of architecture and an independent scholar, a hugely respected voice on the architectural scene.

He wrote for Private Eye for decades penning, under the pseudonym Piloti, (correct) the Nooks and Corners column, founded by John Betjeman. He was also the author of an extensive bibliography, on topics from London’s Victorian buildings to phone boxes, the English house, Greek Thomson and Edwin Lutyens.

His tenure at Glasgow School of Art spanned more than a dozen years, from lecturer in 1990 to senior lecturer until 2003 when he left to take up the Mellon Fellowship research post at Cambridge.

His departure shocked conservationists in Glasgow where he had led the revival in Thomson and was founder and chairman of the Alexander Thomson Society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was an honorary professor at both Glasgow and Cambridge, which paid tribute saying: “He made an invaluable contribution to our MPhil programme over many years, as well as enlivening our community with his wit, erudition and research. We remember him with great affection and respect.”

Stamp was also chairman of the Twentieth Century (formerly Thirties) Society, had a particular interest in 19th and 20th century British architecture and a long-standing interest in the work of the Scott dynasty of Sir Gilbert Scott, the English Gothic revival architect and his descendants.

Since 2004 he had written more than 150 columns for Apollo, the international art magazine, and his 2013 book Anti-Ugly: Excursions in English Architecture and Design, contained many of his Apollo articles. They reflected his love of churches, ancient and modern, his passion for Victorian architecture and other subjects including railways – “still the most civilised and enjoyable form of transport” – and war memorials. He also wrote for Country Life, among many others.

Though he fought for the preservation of countless historic buildings, railing against the redevelopment of much of the country’s urban fabric, he did not necessarily dislike modern architecture – he just detested poor architecture and his lifelong mission was to champion the good.

He is survived by his second wife Rosemary Hill and two daughters from his first marriage to Alexandra Artley, Agnes and Cecilia.

ALISON SHAW