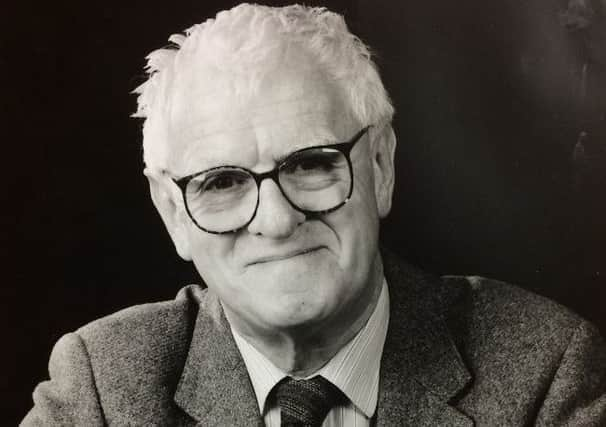

Obituary: Prof Archie Duncan, eminent Scottish historian

Professor Archie Duncan FBA FRSE, who has died at the age of 91, was one of the foremost Scottish historians in the modern era.

He was one of the last of a generation of pioneers who established Scottish history as a subject of academic research in all its aspects. He was also a scholar ahead of his time, whose restless questioning of his own and others’ assumptions and practices made him one of the most intellectually interesting and complex medieval historians of the 20th century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe chronological range of his specialist knowledge, stretching across the entire millennium of medieval history, is unlikely ever to be repeated. He achieved ground-breaking work in analysing charters, chronicles, formularies and parliamentary records, translated Barbour’s celebrated Scots poetic narrative of Robert Bruce’s career and provided new insights into fundamental aspects of medieval Scottish kingship, government, law, and the economy.

Archibald Alexander McBeth Duncan was born in Pitlochry on 17 October 1926. His paternal grandfather had a shoe shop there, and his maternal grandfather was a gamekeeper at Errol.

Most of his childhood was spent in Edinburgh, where his father was a bookbinder. He was educated at George Heriot’s School, Edinburgh, the University of Edinburgh, and Balliol College, Oxford, where he became a tutor. He was appointed in 1951 to a lectureship in History and Palaeography at Queen’s University, Belfast, before joining the Scottish History Department at the University of Edinburgh in 1953.

In that year he published the first significant work on the government of a medieval Scottish king based on a detailed study of 367 documents issued in the name of Robert Bruce. He continued work on this project for most of his career, culminating in his monumental Acts of Robert I, King of Scots, 1306–1329, published in 1988. Not only had he identified more than 200 further documents, but the volume included the equivalent of a monograph on Robert Bruce’s government and administration, transforming our understanding of the mechanisms and practices that underpinned his rule.

As a lecturer at Queen’s University, Belfast, he had also established himself as a pioneer in Scottish social and economic history, particularly through his work on burghs. Although his research and publications gravitated towards the Middle Ages, he maintained a lively interest in all aspects of Scottish history. One of his earliest articles was on an aspect of trade between the Clyde and the Baltic in the 1730s and 1740s, published in 1950.

In 1962, still only 35, he was appointed Professor of Scottish History and Literature at the University of Glasgow–a chair established in 1913 and occupied exclusively by historians, despite its title. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1979 and a fellow of the British Academy in 1985.

He retired in 1993, setting a record unlikely ever to be beaten as the longest serving holder of a chair in Scottish History. He played a leading role in the life of the University of Glasgow, being elected Dean of the Faculty of Arts and, in 1978, Clerk of Senate. During his spell as a university administrator he established a new department (Scottish Literature) and faculty (Social Science). By the time he retired he had expanded the Department of Scottish History to seven members of staff, the largest in any university.

He was, above all, a scholar and teacher, and an inspiration for generations of historians. As a teacher he was passionately committed to opening up Scottish history to anyone who would take a lively interest in it, urging schoolchildren, students and the informed public to follow him in taking nothing for granted.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was a pioneer in the 1980s in teaching early medieval history in an interdisciplinary and comparative course he shared with follow University of Glasgow colleagues Leslie Alcock, a pioneering archaeologist of early medieval Britain, and Patrick Wormald, a medieval historian who redefined the history of Anglo-Saxon England.

Archie Duncan made a wealth of fundamental sources accessible for the first time – especially royal documents, legal collections, and burgh records. For more than 60 years he performed the essential and forbidding task of publishing and analysing texts that could only be made intelligible through a deep understanding and complete technical command of the material.

One of his most remarkable books was Scotland: the Making of the Kingdom, published in 1975, a wide-ranging exploration of Scotland’s development as a kingdom and society up to the 1290s in more than 600 pages. Other history books written on this scale are based on a well-populated field of research. However, there was no such body of work for him to draw on. For large parts of the book he had to start from the raw medieval sources themselves.

Another exceptional book was The Kingship of the Scots. Succession and Independence 842–1292, published in 2002. Most books published long after retirement represent the culmination of views developed decades earlier. For Archie Duncan, in contrast, retirement gave him the opportunity to rethink the subject from scratch, resulting in a panoply of new insights.

His restless intellect was his most inspiring quality, leading to a sometimes shocking capacity to question and undermine long-cherished views of the past. In an age when scholars usually aimed to find enduring certainties, he instinctively saw history as a ceaseless dynamic of fresh insights and discoveries, and expected his own work to be caught up in this process – a process he typically led.

Professor Duncan’s wife Ann predeceased him. He is survived by children Beatrice, Alastair and Ewen, and six grandchildren.

Dauvit Broun