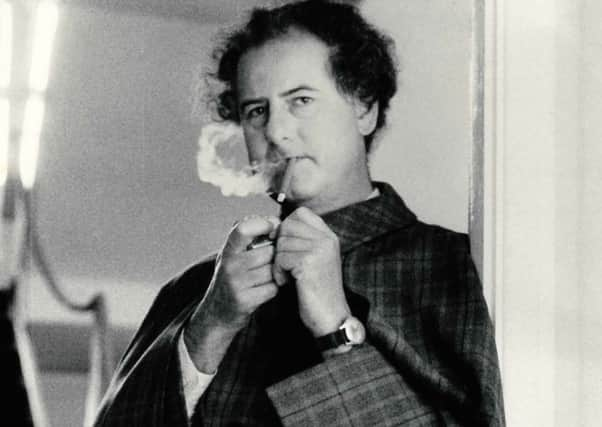

Obituary: Peter Owen, OBE, publisher

Peter Owen was an independent publisher with bewilderingly eclectic taste, who remained true to his philosophy over 60 years, publishing the exciting, the difficult, the foreign, the unpopular and, occasionally, the downright weird, including a fistful of Nobel Prize winners, Yoko Ono’s bland ‘Grapefruit’ and Salvador Dalí’s only novel. All this was achieved while other publishers were falling by the wayside, due to costs, or pandering to the bulk publishing of the latest Sebastian Faulks or another mutation of Katie Price’s autobiography.

Owen’s great skill in backing authors of enduring appeal underlies much of the company’s success. He was a pioneer of quality world literature in translation, counter-cultural writing and specialist non-fiction. He went on to publish a host of brilliant writers, including Hermann Hesse, Shusaku Endō, Jean Cocteau, Yukio Mishima and Tarjei Vesaas, into the English language. Throughout his career, Owen was far more interested in bringing out writers of quality, rather than those who would simply rake in the cash.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFounded in 1951, as Owen’s publishing house grew, he took on staff with the first being fabled Scottish author Muriel Spark, later Dame, author of ‘The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie’, who was his first editor, and wrote a novel partly based on her experience of working in Owen’s office, ‘A Far Cry from Kensington’. Owen went on to publish a number of her novels. Elizabeth Berridge, another novelist, was employed as second editor.

Owen did much of the packing, sales and distribution himself, recalling, “You have to be willing to work like a dog for at least five years to make a go of it as an independent publisher. An amateur must not touch it. Only someone who knows the trade stands a chance.”

Born Peter Offenstadt in Nuremburg, Bavaria, in 1927, he was the only son of an Anglo-German Jewish couple, who ran and owned a leather factory. With Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Peter, who later recalled “vivid and chilling” memories of the Nazis as Nuremburg rallies had been conducted there since 1923, was sent to live his grand-parents in north-west London and learn English. Reluctantly, with the situation in Germany changing, his parents joined soon after and changed the family name.

Upon completing his National Service with the RAF, Owen trained as a journalist but was attracted to publishing. Aged 21, helped out by a service paper quota allotted to him, he went into business with Neville Armstrong. In 1951 Armstrong bought him out for £500 and with £350, promised by his mother, Owen set-up his own publishing house, Peter Owen.

Owen’s first list of publications included Henry Miller’s ‘The Books In My Life’, an anthology of Russian literature that included Ezra Pound and the then almost unknown author Boris Pasternak, who would go on to pen ‘Dr Zhivago’ and turn down the Nobel Prize. Owen’s first major triumph was snapping-up Hermann Hesse’s cult classic ‘Siddhartha’ - the book that arguably kicked off the 60s counterculture - for a £25 advance. He eventually secured the biggest royalty deal ever struck for a paperback with Pan, and the novel did more than any other to prevent Owen’s firm from collapsing

Although Hesse had won the Nobel Prize for literature, virtually no one at that time outside his native Germany had ever heard of him. This early coup meant business was set to boom in the 60s and 70s. Later he almost lost Hesse for daring to ask his widow if the title of his 1930 classic, ‘Narcissus and Goldmund’, might be changed.

Spark’s literary taste and judgment urged Owen to sign another future Nobel Prize winner, Samuel Beckett, but Owen did not. “Beckett was getting on for 50, had never made it (before ‘Waiting for Godot’),” he recalled. “We had a choice between Beckett and the Japanese Osamu Dazai. Muriel said, can’t we do both? I said we can’t afford both, and chose Dazai.”

He pioneered bringing Japanese literature to Britain. In 1960 he published Mishima’s semi-autobiographical ‘Confessions of a Mask’, which made his reputation, but the success of that book meant that Mishima moved on to a bigger house for more money.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe counted Francis Bacon among his friends and thrice visited the Spanish home of Dalí to gain the English language rights, illustrations and signatures for the arch-surrealist’s only novel, ‘Hidden Faces’. He also met and published Anaïs Nin, Anna Kavan, Paul Bowles, William Donaldson (Henry Root) among many others.

Within the publishing world Owen was known for his careful accounting; he paid minimal advances, negotiated subsidies for translations and his prices were higher than the norm, but he paid his staff well and only took a small wage himself; he also typed out his authors’ royalty statements with two fingers on an old typewriter. Wherever translations were concerned, he bought them cheaply from the author’s American publishers. He was also a supreme seller of foreign rights.

Owen married twice, firstly, in 1953, to Wendy Demoulins, who wrote novels as Wendy Owen, and then in 1987 to Jan Treacy, a former actress; both marriages were dissolved. He is survived by two daughters and a son.