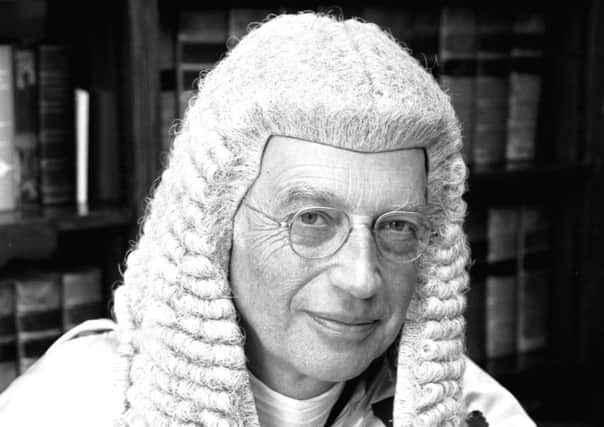

Obituary: Lord Ronald King Murray, politician and lawyer

Ronald King Murray, who has died aged 94, was at the forefront of Scottish public life for decades as politician and eminent lawyer, latterly Judge in the Court of Session and High Court of Justiciary. He was strongly identified with the anti nuclear weapons movement, which he championed through a number of avenues including the World Court Project.

Between 1970 and 1979 he was Labour MP for Leith, Lord Advocate in the Wilson and Callaghan governments from 1974-79 and Senator of the College of Justice, Judge, between 1979 and 1995.Thereafter he resumed his active support for the anti-nuclear cause, until shortly before his death.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe stood unsuccessfully as Parliamentary candidate in a number of elections prior to securing his Leith seat.The first was in 1959 in Caithness and Sutherland, while the following year he stood in Edinburgh North. During that campaign, he stated in a speech: ”The time has come for us to put an end to the UK’s independent deterrent should the summit talks on disarmament fail.” His Conservative opponent Lord Dalkeith’s supporters accused Murray of “mud slinging” in reference to Dalkeith’s aristocratic status, a claim strongly denied.

Four years later he stood twice in Roxburgh, Selkirk and Peeblesshire, latterly against David Steel, but it was not until 1970 that he tasted electoral success, in Leith, and he became a hardworking MP. Simultaneously his legal career continued apace. Admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1953, he initially enjoyed a mixed civil and criminal defence practice before being appointed Advocate Depute, prosecutor in the High Court, in 1964.

In 1967 he became Queen’s Counsel. On entering Parliament he initially acted as shadow spokesperson on Scottish legal affairs. He opposed Edward Heath’s Industrial Relations Bill as an attack on white collar trade unionism and also opposed his Bill to take the country into the Common Market, stating it was “constitutionally wanting”. Following re-election in 1974, he was appointed Lord Advocate by the Wilson government, a role he fulfilled with distinction until 1979.

During that period he had to deal with a number of complex and sensitive issues. Peter Hain and the Young Liberals sought to have him impeached in Parliament over the controversial Paddy Meehan case.Meehan had been convicted of murder in Ayr in 1969 but following a campaign to have the conviction overturned, Murray lent his support to seeking a Royal Pardon, which was granted. Another man, Ian Waddell, was tried but acquitted, leading to criticism from the original trial judge Lord Robertson. Liberal leader Steel refused to table the motion for impeachment.

Years later, Murray said that while the idea of impeaching him was “misconceived, “it was technically possible to do so to a Law Officer”.

He also played an important part in the repeal of Scotland’s criminal law against homosexuality, his assurance that acts in private between consenting adults would not be prosecuted paving the way for progress of the legislation.

Tam Dalyell recalled Murray did endless amounts of hard work piloting Scottish legislation through Parliament and was considered a very safe pair of hands. He was a real workhorse – and I mean that in the most affectionate way. Many colleagues and I had cause to be grateful to him for the legal advice on constituents’ problems he dispensed freely and courteously to us.”

Elevated to the Bench in 1979, he carried out his judicial duties very ably and enjoyed a well-earned reputation for overriding fairness, imperturbability and consistent courtesy to all with whom he dealt. Blessed with an enquiring mind, he relentlessly pursued the answer to complex legal problems. Whether intentionally or not, he could also provide lighter moments against a backcloth of dark deeds. One observer recalls that during a trial in the High Court for attempted murder, the principal prosecution witness described how just before he went to cross the road to buy a fish supper late one evening, he stood in shock as he saw a fracas taking place involving a stabbing. He gave considerable detail to the prosecutor before Murray, about to invite the defence to cross examine, asked him, ”And did you get your fish supper?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMurray’s stance against nuclear weapons had its roots in his war service. Tam Dalyell recalled that while Murray was a Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers officer in South East Asia Command, “he was appalled by the potential disaster the servicemen in the Far East saw unveiled at Hiroshima and Nagasaki”.

He was a staunch supporter of the World Court Project, an alliance of peace campaigners, lawyers and doctors, who obtained an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice in 1996 suggesting the illegality of nuclear weapons. Aged 84, along with other lobbyists – including the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland – he was refused access to Aldermaston Atomic Weapons Establishment by armed police.They had intended to investigate nuclear weapon production.

The son of an electrical engineer and nephew of judge Lord Birnam, Ronald King Murray attended George Watson’s College, Edinburgh.After war service he obtained a 1st class honours degree at Edinburgh University in philosophy before undertaking a law degree there while teaching moral philosophy.

Therafter he studied at Jesus College, Oxford, where later he was made Honorary Fellow. In 1950 he married Sheila Gamlin at Stoke Bishop, Bristol, whom he had met in Edinburgh. He had interest in a wide range of subjects including astronomy and science and enjoyed sailing. He is affectionately remembered by many and recognised for the important contribution he made to Scottish public life.

He is survived by daughter Nicola, son Diarmid and three grandchildren.

JACK DAVIDSON