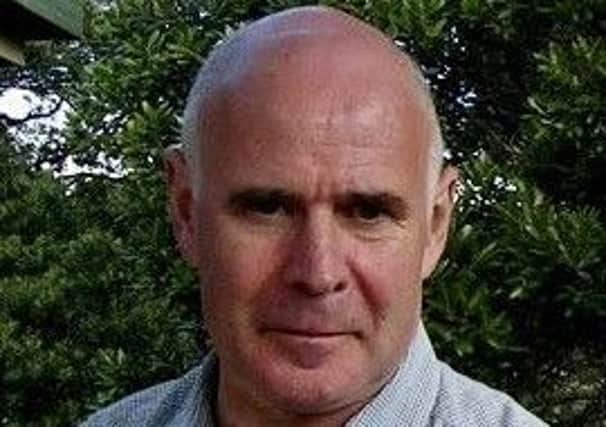

Obituary: Gordon Kirk OBE, educationalist

Gordon Kirk was one of the movers and shakers in Scottish education from the 1970s until the early 21st century, and thereafter advised government on education across the whole United Kingdom .

Born the son of a plumber, he showed academic brilliance and rose to be a long-serving and notable Principal of the teacher training college Moray House; Vice-Convener of the General Teaching Council for Scotland; and Vice-Principal of Edinburgh University.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlways concerned about the social aspects of education, he helped redesign the Scottish secondary school curriculum; served on many national bodies; and in 2003 drew the wrath of some in the Scottish Tory party with ground-breaking ideas to broaden undergraduate admissions to Edinburgh University.

A man of commanding presence, Kirk stood his ground: “We are not lowering our requirements for certain groups of people,” he explained. “We are asking everyone to meet a certain threshold, and only then looking at other relevant factors.” There was little new in the idea, he contended: potential medical students, for example, “have to show they can stand the sight of blood”, and as for potential teachers, “We all know there are perfectly able students who would not survive a fortnight in the classroom.”

He sought, he said, an admissions system that could identify qualities such as commitment and resourcefulness.

Kirk brought to the debate many years of experience serving on the Council for National Academic Awards (CNAA); and from the 1980s until 2002 on the General Teaching Council for Scotland, of which he was Vice-Convener from 1992 until 2001. He was one of the first educational leaders to be consulted by MSPs in committee after the birth of the new Scottish Parliament in 1999. He was appointed OBE in 2003.

In recent years, after his retirement, he expressed disquiet about the state of education in Scotland.

Kirk was, in the 1970s, one of those credited with maintaining Scotland’s high reputation for educational excellence as a member of the Munn committee, set up by Scottish Secretary Bruce Millan and led by the former Indian Civil Servant Sir James Munn, which considered the curriculum that should be taught in Scottish secondary schools, reporting in 1977.

Much later Kirk, as Academic Secretary to the UK-wide Universities’ Council on the Education of Teachers, was to write an influential response to the Blair government’s 2003 initiative Every Child Matters, drawn up after the death in 2000, at the hands of her guardians, of eight-year-old Victoria Climbie. Kirk favoured the initiative’s expressed aspiration to have “joined-up” educational services, and his comments are quoted in at least one recently published book.

Kirk is remembered in particular for his fine stewardship of the 150-year-old Moray House in Edinburgh through what had been troubled times for teacher training in the 1980s, when a number of colleges were closed. As Moray House’s Principal from 1982, he was, it is recalled, “a breath of fresh air”, preserving the institution’s independence, and having its courses validated to a national standard by the CNAA. On the CNAA’s dissolution in 1993, Kirk oversaw a validation arrangement with Heriot-Watt University; but when Moray House staff sought to keep their own ideas on some courses, he negotiated, from 1998, a relationship with Edinburgh University that proved more comfortable. Moray House became the University’s Faculty of Education. Kirk was Dean of the Faculty until 2002, when he became the University’s Vice-principal, and chaired a committee on admissions policy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGordon Kirk, tall, athletic – he had gained a Full Blue and competed at football for Scottish universities while studying at Glasgow – and a highly skilled bridge player, never neglected the question of morale.

He is remembered for delightful Burns Nights held at Moray House, and could put over a funny story – colleagues recall as hilarious his telling of how, when stopped by police while driving in the United States, he had protested that he had not been speeding, but merely following the car in front. “That”, the officer solemnly told him, “is an undercover car.”

Kirk was educated at Camphill Secondary School, Paisley, and went on to Glasgow University, where he studied English Language and Literature and French, and graduated MA.

He worked as a secondary school teacher in Glasgow while studying for a Masters in Education under Professor Stanley Nisbet. In 1965 he took a post as lecturer in education at Aberdeen University, working with Nisbet’s brother, Professor John Nisbet. In 1974 Kirk became head of the education department at Jordanhill College of Education, Glasgow, staying until his move to Moray House.

He had met, at Glasgow University, Jane Murdoch, a fellow teacher, and they married in 1967, living in Aberdeen and later at Milngavie.They would have a daughter, Heather, and a son, Graham. All three, with his only sibling, Linda, survive him. The family later lived at Gullane, East Lothian, where he played golf.

He and Jane, who specialised in teaching those with learning difficulties, thrived on arguing out educational questions together. A love of music, shared with his wife and children, drew him to join the Scottish Episcopal Church.

He completed, at the age of 60, a PhD on educational policy, and was author or editor of many publications, including Scottish Education looks Ahead (1969); and Teacher Education: The Policy Debate (2015).

Kirk’s habit of thoughtful note-keeping throughout his career revealed, however, his Achilles heel: the only subject, friends acknowledge, in which top marks eluded him was handwriting.

ANNE KELENEY