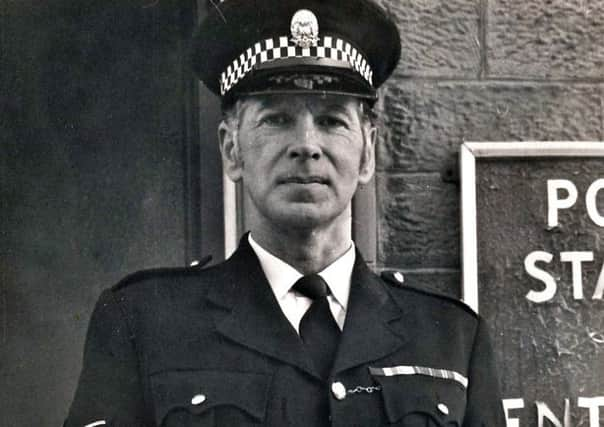

Obituary: Duncan Cormack, policeman and war veteran

Duncan Cormack’s first mission to the beaches of Normandy, before dawn on D-Day, was a quiet affair: the 19-year-old landing craft coxswain transported 25 Navy frogmen to within 50 yards of Gold Beach an hour before the historic attack was launched.

The divers were to clear the beaches of mines and bombs before the arrival of thousands of troops. Setting off from his depot ship, the SS Empire Rapier, at 4:30am on 6 June 1944, Cormack guided the vessel through the blackness towards the coast, lowered the ramp and the frogmen slipped silently into the water, swimming to shore. He never saw or spoke to them. The only sound was the wind.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen, halfway back to the Empire Rapier, hellfire erupted – every gun on every battleship began targeting the beach, scores of rockets soared overhead and occasionally one would lose momentum and cascade down towards the landing craft, necessitating a swift change of course. As soon as the Germans began replying to the barrage, casualties were inevitable.

Cormack completed eight trips that momentous day and on each mission two or three troops immediately perished in the surf: “They just collapsed, shot, machined gunned… there was nothing we could do for them – just reverse because another landing craft was behind me. And so it went on like that, like buses, back and fore, back and fore.”

“We couldn’t go and get them but the very idea that we put them there… we didn’t like it. We put them to their deaths in a way,” he told his local paper almost 70 years later, “but there was no point in judging that, in thinking about it. We just stopped thinking about it but we shed a tear just the same, we couldn’t help it.”

Cormack was a boy of 15 living in Wick when he experienced the reality of war for the first time – watching awestruck as a crippled Heinkel bomber came down in the town. Seventy-five years later, having survived the conflict and all its bloody consequences, he was decorated with the Legion d’Honneur, France’s highest award, for his part in releasing the country from Nazi rule.

Born at the Old Police House, Reay in Caithness, where his father Donald was a sergeant, the family later moved to Wick and he had just left high school when a stricken enemy plane was forced to land. Its crew were held at the local police station where his father, who was on duty, later entertained his son with tales of the Prisoners of War.

Young Cormack was already working at the local aerodrome’s NAAFI stores and was called up for active service in 1942. Looking for excitement and intrigued by the opportunity of commando training, he opted to join the Royal Marines. He trained in Devon and Wales before being introduced to landing assault craft at South Queensferry on the Firth of Forth. From there he went to Invergordon on exercises and, after gaining his coxswain’s qualification, joined the Empire Rapier which sailed to Southampton.

In the run-up to D-Day the marines trained along the Dorset and Cornish coasts in preparation for the ambitious assault flotilla which they were utterly determined would succeed. The mission had been scheduled for 5 June but bad weather delayed the plan and when Cormack set off on Operation Neptune the following day it was still choppy, leading to seasickness among the troops.

During the day the ferrying of troops was constant, as was the smoke, fire and death all around. “We said ‘Oh hell, we keep going and that’s it …when we got to the beach it was a case of down ramp and troops off,” recalled Cormack.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBack on the Empire Rapier he and the other exhausted marines gathered in the mess room to reflect on the comrades who were never coming home. “We couldn’t do anything for them, they were gone. That was it.”

Next day the operation began again, shipping another 500 troops from Southampton, but this time there was no rifle or machine gun fire. Their courage and faith in the mission was paying off. In all he made 30 trips in the following weeks, then sailed to Holland and Belgium. After the German surrender he spent VE Day in port in Southampton before heading to the Channel Islands, to take German POWs back to Southampton, and then on to Cornwall where the landing craft were left.

But the war with Japan was not yet over and Cormack was soon on board the infantry ship HMS Glengyle to Ceylon, then on to Bombay before hearing of the Japanese surrender. After being seconded to the Australian Navy he helped take troops to the port of Kure in Japan, near Hiroshima, where he witnessed the devastating legacy of the atomic bombs that had brought Japan to its knees.

Demobbed in 1946, Cormack returned home and gave barely a second thought to his war service – until retirement. By that time he had followed his father into the police, joining Caithness-shire Constabulary, later to become Northern Constabulary, and spending 30 years in the force. Posted to Wick, Castletown and Thurso, he retired as a sergeant in 1977 before working for a further decade as a driving instructor.

But there was one event during the Second World War that had blighted the whole community of Wick and in retirement he and his wife Elsie, whom he had met through her work in fiscal’s office, ensured it was never forgotten. The town had been mainland Britain’s first victim of a daylight enemy raid when a Junkers 88 aircraft emerged from low cloud, on July 1, 1940, to drop its deadly load on the civilian population. It was late afternoon and youngsters were out playing in the densely populated Bank Row. Two bombs killed 15 people, ten of them aged between five and 16. Among them were Elsie’s little sisters, Amy, nine, and Bertha, five. Three months later two more children and a woman were killed in a Nazi raid on RAF Wick’s aerodrome.

Cormack, whose father was on patrol in the Bank Row area at the time and suffered shrapnel wounds, became a director of the charity Second World War Air Raid Victims – Wick formed by relatives of the dead. Elsie served on the organising committee of its initiative to create a memorial garden on the site which was opened in 2010, 70 years after the tragedies.

In 2016 Cormack, who had attended ceremonies in Arromanches to mark the 50th anniversary of D-Day and who was also a Burma Star veteran, saw his own courage during the conflict recognised with the award of the insignia of Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur, presented to him in Aberdeen.

Predeceased by Elsie, who died in 2013, he is survived by their three sons, two daughters and seven grandchildren.

ALISON SHAW