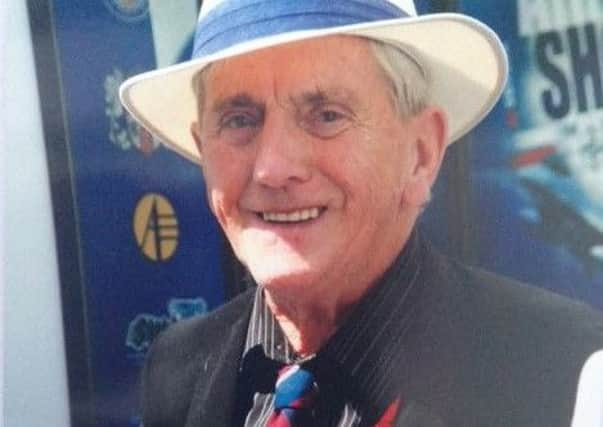

Obituary: David Lambert, slater, plasterer and RAF veteran

Long before they reached the besieged city of Warsaw, the crew of the Handley Page Halifax could see the glow on the horizon. The Polish capital was fiercely ablaze.

Its inhabitants, who had endured five years of brutal Nazi rule, had finally risen up against their oppressors and a loyal underground army had begun to attack and capture strategic installations. In retaliation, Heinrich Himmler, leader of the SS and Gestapo, had ordered the killing of all citizens and the razing of the capital.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe job of the RAF’s 148 Squadron, Special Operations Executive, that summer of 1944 was to deliver vital supplies to the beleaguered Polish forces and an Allied airdrop had been under way for several days by the time David Lambert and his fellow airmen were ordered to take off from Brindisi, on the southern Adriatic coast of Italy.

It was one of the longest and most hazardous journeys they would make, nearly 15 hours non-stop, almost all of the route over enemy territory. Over the previous two days the squadron had lost four aircraft on such missions and understandably they were apprehensive.

“It was rather terrifying to think of the length of time we were going to be flying, which was longer than any flight we had ever done before,” a candid Lambert later recalled.

They left at 7:30pm on 14 August and as they approached the target, just before 1am the following morning, the destruction ahead was evident. Pilot Larry Toft hugged the course of the Vistula River at just 300ft, quickly attracting an incessant barrage of anti-aircraft fire. The plane took a hit and, though not disabled, filled with smoke and the stench of burning.

Despite the sea of flashes and flames surrounding them, Lambert, the dispatcher, was unable to see the battle ensuing outside. Buried deep in the centre of the aircraft he was desperately watching for the green light from a panel by a hole in the floor – the signal to launch the cargo of aid packages earthwards.

The crew was well-versed in similar operations as their previous special duties had included dropping supplies and agents to the French Resistance. On those occasions their target would be marked by partisans holding torches at four corners of the drop site. They were to expect the same torchlight method to identify the location, Napoleon Square (now known as Uprising Square) where they were to deposit the supplies. Girls, positioned on the roofs of buildings, would hold the torches.

But that night the bravery of the young women was met with rifle fire from the Germans who shot them off the roof, only for another girl to immediately take the place of the victim. Thanks to their heroism and the skill and courage of the aircrew, Lambert and his fellow airmen made a successful and accurate drop. They all returned safely to base at 10.20am.

The crew completed two further and equally hazardous missions to Warsaw on 16 and 18 August.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTragically the uprising was defeated after 63 days and the cost was horrendous, with thousands of fighters killed or sent, along with 55,000 civilians, to concentration camps, 200,000 inhabitants dead and more than 10,000 buildings destroyed. The Allies lost an estimated 360 airmen and 41 planes.

Their missions had been hampered by being prevented from using Soviet airfields, meaning they had to operate from distant European bases which reduced the payload and the number of sorties, making it impossible to drop enough supplies to support the rebellion.

However their valiant efforts were repeatedly recognised down the years by the Polish people – Lambert returned to Warsaw to receive medals from the presidents of both Warsaw and Poland and, at home in Scotland, was presented with the 70th anniversary commemorative medal by the Polish consul on behalf of the Association of Warsaw Uprising Insurgents.

He was also reunited for the first time in seven decades with two of his Halifax crewmates, Larry Toft and Jim McKenzie-Leith, when they took part two years ago in a Polish television documentary, Warsaw 44: The Uprising, alongside a restored Handley Page Halifax.

But that vital aid mission, which he brushed off as “only doing what they were told”, was not the only defining chapter in his war: nine months before the uprising his aircraft had crashed into the North Sea as he returned from operations over Stuttgart. It was November 1943 and their Halifax was hit by flak, rendering their port outer engine useless. On the home run they overshot Thorney Island twice and ditched in the water. Young Lambert, then only 19, had survived in the bitterly cold waves by using his emergency dinghy, a feat that earned him membership of the Goldfish Club, an exclusive organisation for those who cheated death after “coming down in the drink”.

The club was the idea of chief draughtsman of the rubber company P B Cow which was often visited by wartime crewmen who owed their lives to the “Mae Wests” – life vests – and rubber dinghies the firm produced. Named to reflect the value of life (gold) and the sea (fish), its badge features a winged goldfish flying above two blue waves. Word of the club spread as far as Prisoner of War camps from where eligible aircrew are said to have claimed membership.

Lambert, a former Dunfermline High School pupil, who had enlisted as an 18-year-old with the RAF Volunteer Reserve, flew mostly in Halifaxes with 420 and then 624 Squadrons.

After training in parachuting he became a dispatcher involved with Special Duties operations over France. He was later posted to North Africa and then Italy where he joined 148 Squadron and was involved in the missions over Warsaw and Yugolsavia, Albania and Greece, dropping agents and supplies behind enemy lines.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter the war he served as an inspector of recruiting for the RAF in Dundee and Edinburgh until 1947 when he returned to the family slating and plastering business in Inverkeithing where he worked until retiring at 65. During the 1960s he also found time to become a special constable.

A past president of Dalgety Bay Probus Club, a keen curler and golfer, he was a founding member of Pitreavie Castle Curling Club and played at Aberdour Golf Club for more than 50 years.

Predeceased by his wife Myrtle, whom he married in 1948, he is survived by their son Stephen and daughter Pamela, four grandchildren and three great grandchildren.

ALISON SHAW