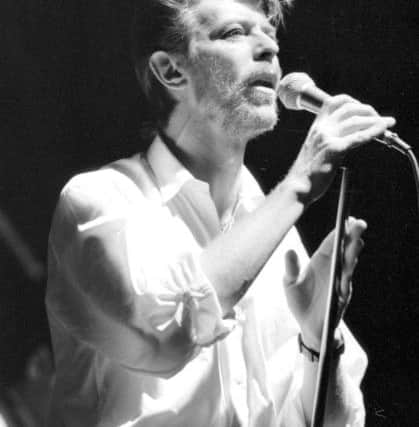

Obituary: David Bowie, musician, actor, cultural icon

Across the world and generations, many millions of us loved David Bowie for the music he made, the person he was and the clarity with which he showed us that being who you want to be is often just a simple question of focus and confidence. He was one of history’s beautiful outsiders, a self-made figurehead for those whose tastes and sexuality lay beyond the orthodoxy of the late 20th century mainstream. Many imitated him, but Bowie’s acute self-knowledge in terms of image, musical style and the razor-sharp emotional content of his work marked him out as an all-too-rare original.

In years to come, many of those fans might see even the circumstances of his death as the last act in a perfectly-synchronised body of work. Diagnosed with cancer 18 months before his death, a fact which wasn’t made public until the after-the-fact announcement, he set to work recording his final album, Blackstar. A towering, typically unique and in places unnerving record, it was scheduled for release on Bowie’s 69th birthday, on 8t January 2016; two days after it came out, he died, and the record’s true purpose as his own oblique epitaph was revealed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat endured about Bowie in comparison to contemporaries of similarly huge significance wasn’t just that he recorded a huge amount of iconic and enduring music in the early years of his success, but that his semi-regular comebacks would try to advance his sound and image, moulding trends in popular culture around him.

In the late 1960s, his career came slowly to life through modish pop and psychedelia, first with his band Davy Jones & the Lower Third, and then the 1967 hit The Laughing Gnome (which was subsequently airbrushed from history on compilations and so on), before achieving an otherworldly hit with Space Oddity in 1969, buoyed by its thematic links to the recent moon landing. Despite this, the immediately following years weren’t an unqualified success. The 1969 Space Oddity album and its follow-up the next year, The Man Who Sold the World ,sold middling amounts, and 1971’s Hunky Dory was only successful in the UK; its now-iconic single Changes didn’t chart.

It was 1972’s concept album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars which recast Bowie as the otherworldly glam rock star Ziggy and broke him as a truly iconic figure, not least for a still-remembered performance of Starman on Top of the Pops which broke perceived boundaries of sexuality for the time thanks to Bowie and guitarist Mick Ronson’s flirtatious body language.

The rest of the 1970s belonged to Bowie in the UK, and he eventually broke the United States too. The albums Aladdin Sane, Pin-Ups (both 1973) and Diamond Dogs (1974) were all British number ones, spawning iconic hits like The Jean Genie, Life On Mars? and Rebel Rebel, while Fame from 1975’s soul-influenced Young Americans record was not just his only significant US single hit of the decade, but his first number one in the country.

In the latter half of the decade, Bowie’s style altered radically with a move to the artistic melting pot of West Berlin, in an attempt to get clean from the prodigious levels of cocaine abuse and addiction he had fallen into as a resident of Los Angeles. He worked with fellow émigré Iggy Pop on the latter’s albums The Idiot and Lust for Life, and with producer Tony Visconti (with contributions from Brian Eno) created the Berlin Trilogy of Low, Heroes (both 1977) and Lodger (1979). The former album is seen by many critics as his masterpiece; the middle is titled after one of his most enduring and affecting songs.

It was an odd period for Bowie, during which his commercial success faltered even as critical respect for him soared. Back home in London, punk was in full swing, a genre his music completely bypassed, and yet he was the only already-established star most of its instigators had respect for.

In 1980 Scary Monsters & Super Creeps launched him back into the mainstream, bearing the significant hits Ashes to Ashes and Fashion, and 1983’s Let’s Dance was his commercial high water mark.

Using a sleek disco sound akin to producer Nile Rodgers’ former band Chic (Rodgers also produced for Duran Duran and Madonna at the time), the record was seen as an unwelcome step into the mainstream by Bowie’s more devoted fans, even as the wider public were thrilled by it. In retrospect Let’s Dance (his second and final US number one), China Girl and Modern Lovers were as sublime and mature pop songs as any he wrote. The accompanying Serious Moonlight tour took him into stadiums for the first time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the 1980s he collaborated with Queen (Under Pressure, 1981), Bing Crosby (Peace On Earth/Little Drummer Boy, 1982), Tina Turner (Tonight, 1984) and Mick Jagger (Dancing in the Street, 1985), and then hit his first critical bump with the poorly-received rock group Tin Machine. In his last two decades, any new album was still an event release, notably the 1996 drum ‘n’ bass experiment Earthling (Britpop was another ignored fad) and particularly 2013’s acclaimed comeback after a decade away, The Next Day.

Born in Brixton to parents Margaret and Haywood, David Robert Jones was raised in Bromley, Kent, where he first heard rock ‘n’ roll like Little Richard’s Tutti Frutti and later developed an interest in jazz. Such was his diversity as an artist, that his acting career alone was significant. Perfectly cast by director Nicolas Roeg as the alien Thomas Jerome Newton in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), he worked for the famed directors Tony Scott (The Hunger, 1983), Martin Scorsese (The Last Temptation of Christ, 1988), David Lynch (Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, 1992) and Christopher Nolan (The Prestige, 2006). He starred in iconic children’s fantasy Labyrinth (1986) and made send-up appearances as himself in Zoolander (2001) and Ricky Gervais’ Extras (2006).

In his life, David Bowie was given two Grammys, three Brits, an Ivor Novello award, Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame and Science Fiction & Fantasy Hall of Fame inductions, and an honour from the French government, although he turned down an OBE and a knighthood. Of the many potential and now much-shared lyrical eulogies he wrote for himself, “My death waits to allow my friends / a few good times before it ends / so let’s think of that and the passing time” from the Ziggy era’s My Death is only one of the most appropriate. He is survived by his second wife, the model Iman, and his children Duncan and Alexandria.