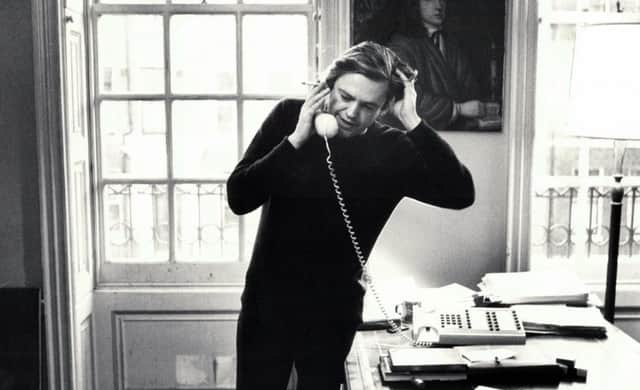

Obituary: Alexander Chancellor, editor who rejuvenated The Spectator and steadied The Oldie

A sad crowd of veteran journalists gathered this weekend in Northamptonshire for the funeral of Alexander Chancellor, who earned his reputation as ‘the editors’ editor’ when rejuvenating The Spectator in the seventies, launching The Independent Magazine in the nineties and steering The Oldie from crisis to calm in the last two years of his life.

Alexander Chancellor was born and brought up in England but his heredity was Scottish. Chancellors had been lairds of Shieldhill in Lanarkshire for centuries. Today the house is a hotel with a ‘Chancellor’ honeymoon suite, once slept in by Nelson Mandela. The family moved south when his grandfather pursued a military and colonial career, eventually high commissioner for the British mandate of Palestine and Transjordan. Chancellor, who delighted in absurdity, was amused to discover his grandfather’s attempt to quell a rebellion, by an aerial drop of propaganda leaflets, backfired when the wind blew in a counter-productive direction.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChancellor’s journalistic respect and dedication came from his father, Sir Christopher, a double-first in history at Cambridge, who ended his career as chairman of Reuters worldwide. Despite spending his adult life in the Far East and England, Sir Christopher insisted on being buried at Shieldhill. Humour Chancellor inherited from his mother Sylvia Paget, who met her husband at Cambridge when one of the earliest female undergraduates. She was a daughter of the physicist and baronet, Sir Richard Paget. In old age she founded the Prisoners’ Wives Association.

Chancellor was the youngest of four children, all of whom achieved significance in the arts. In his infancy a German bomb struck the house his parents had optimistically rented in St Paul’s churchyard. He slept throughout, to his mother’s pride; a sign perhaps of the social ease and sangfroid to come. Chancellor followed his father to Eton, where he was the school’s star pianist. A musical career beckoned, but for someone so amused by the world it was never a serious option. It was typical of his modesty that he played classical pieces in private, preferring to entertain his friends with such music hall songs as ‘Joshua, Joshua, sweeter than lemon squash you are’.

After Cambridge, where fun took precedence, he joined Reuters. He married Susanna Debenham in 1964 and soon ran the Reuters office in Rome and Paris. In Rome their house was a virtual hotel for visiting friends; in Paris they were hardly disturbed. This reflected their own preference. Chancellor spoke flawless Italian. A Tuscan farmhouse was bought and remained a favourite refuge of his family, now including two daughters, Eliza and Cecilia, In his sixties he fathered another daughter, Freya, with the writer Emily Bearn.

He was back in London at a career cross-roads when a friend Henry Keswick, whose father had been Sir Christopher’s best man, bought The Spectator and offered Chancellor the editorship because he was the only journalist he knew. Keswick, taipan of the famous Scottish Hong-Kong based trading house of Jardine Matheson, was the ideal, unquestioningly patrician, proprietor. The magazine’s admirably defiant obsession with British independence of Europe had led to declining sales. Chancellor made it eclectic, contrary, surprising, ‘above all,’ as Stephen Glover wrote, ‘fun’.

He had no editorial experience, literary ambition or political opinion beyond a gentle liberalism, but modesty proved a key editorial attribute. He took colleagues’ advice and acted upon it. He was recklessly generous: problems were solved over convivial lunches when he automatically did the honours with or without expenses. He had a native suspicion of compliments, delivered or received, but always respected others’ amour proper: copy was sacrosanct and went un-subbed; proprietors’ balance sheets were secondary to journalists’ needs. It was appropriate the last column of his life was a defence of press freedom; for this reason his award of the CBE for services to journalism gave him undisguised pleasure –‘It’s silly I know…’.

His jokes were invariably at his expense. Who else would have written at length about his wedding trousers collapsing round his ankles as he shook hands with the bride? He employed friends like Auberon Waugh, whose musical and literary son Alexander married Eliza (Cecilia became the international model) but gave first breaks to the young: Timothy Garton Ash, reporting on the discontent of the Soviet Eastern Bloc; the 19-year-old caricaturist John Springs. The weekly Spectator lunch, cooked by the future tv ‘Fat Lady’ Jennifer Patterson, became legendary (Jennifer: ‘Don’t you like bunny, dear?’ Kingsley Amis: ‘No I do not like bunny.’).

Today’s Spectator is a commercial success but the glamour, the danger, has gone.

To launch The Independent Magazine Chancellor heeded Patrick Marnham ‘no gardening, travel, fashion or cookery’ and the photographer and picture editor, Bruce Bernard, ‘no colour’. The success of the reactionary black-and-white result defied the odds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis only book, Some Times in America, is an essential warning for anyone rashly pursuing the American dream. He left The Oldie , now to be edited by Harry Mount (b. 1971), son of his friend Ferdinand Mount, with a rising circulation and tidier design. His death deprives journalism of a champion of freedom and fun.

John McEwan