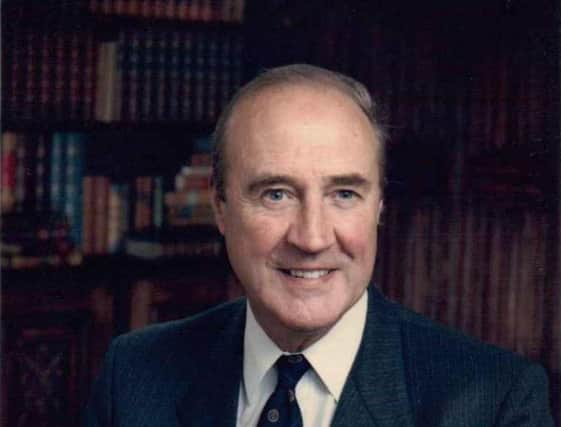

Obituary: William Mutch OBE FRSE FICFor, forestry expert and author

Bill Mutch may have been born in England’s industrial heartland but his greatest love was the wild countryside, its forests and the beauty of the natural environment, be it Africa, Austria or the rural expanses of Scotland.

His lifelong interest and expertise in trees and the role they play defined him as a leading academic in the field of forestry, sought out by governments from China to Costa Rica and highly respected at home for his work as head of Edinburgh University’s forestry and natural resources department.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdContinually driven by a desire to educate others about the importance to the world of forestry, he wrote widely on the subject and latterly, despite a debilitating lung condition, was still coming up with ideas for new projects.

It was a quest that he had pursued over a career spanning more than half a century and, heartened to see a television piece about forestry just days before he died, he finally conceded: “At last I am beginning to get the message over.”

His mission began in Nigeria in 1946 with his first job after leaving university in Edinburgh. Although born in Salford where his father Wilfred, a professional artist, had his own business designing advertisements, he was baptised and schooled in the Scots capital where his grandfather had been session clerk and precentor at Cramond Church.

His mother Helen who, as a young woman, had looked after industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie’s children in New York, had two sisters still living in the family home at Davidson’s Mains and, after prep school, young Mutch was sent to Scotland to be cared for by them while he attended the nearby Royal High School of Edinburgh.

At one time the youngster had considered a career in geology but his headmaster, a classicist, had insisted he take Greek and Latin and as a result he left school with no science qualification. By the time he had done a crash course in science he had settled on a future in forestry and ecology.

An accident at school, when he was impaled in the neck during an exercise with the Officer Training Corps, left him unfit to serve during the Second World War but that meant that he was able to undertake and complete his studies, a BSc and PhD in forestry.

He went on to serve in the Colonial Forest Service as a district forest officer in Benin, Nigeria from 1946 to 1952, overseeing a staff of 25. These were the some of the happiest years of his life, enhanced in 1950 by marriage to childhood friend Margo, who joined him in Africa.

However, their time there was brought to an end when he was invalided home, suffering from dengue fever and amoebic dysentery. He spent several months recovering in hospital in Edinburgh before taking a research post at Oxford University.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy 1953 he had returned to Scotland to take up an appointment as a lecturer to Edinburgh University’s forestry department. In the late 1950s and early 1960s he edited the publication Scottish Forestry and was promoted to senior lecturer in 1963, publishing his survey Public Recreation in National Forests a few years later.

During the 1970s he became involved in looking at the economics of land use, particularly during a long research project on red deer management in the north-west Highlands, and in 1981 he was appointed to head the Edinburgh University department that had by then become forestry and natural resources.

By now he had established an international reputation and the next two decades saw him involved in myriad organisations. He was president of the Institute of Chartered Foresters (ICF) from 1982-84, steering it to Royal charter status, was awarded the OBE for services to forestry in 1985 and the ICF’s gold medal the following year.

Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1987, he went on to become director of Central Scotland Woodlands Ltd and a member of the Countryside Commission for Scotland and the Nature Conservancy Council. He was also Scottish Natural Heritage’s first regional chairman for south-east Scotland.

The last ten years of his career saw him working as a forestry and land use consultant. He advised the governments of India, China, Costa Rica and Sudan on forestry policy and forestry education and led two parties, including foresters, planning officers and heads of timber-related industries, to demonstrate a wide range of differing woodlands in the Netherlands and Germany.

Meanwhile, he continued to produce academic papers and publications, including the books Farm Woodland Management and Tall Trees and Small Woods. In retirement he also turned his hand to fiction, becoming a thriller writer, drawing on his both own knowledge and a real life Second World War incident in Nigeria.

His first thriller, Steal Me A Duchess, was based on an episode involving some of his former colleagues in the Colonial Forest Service, and there is a possibility it could be made into a film.

His second, Eskdale Shoot, is set in the Scottish Borders and features some of the same characters. It was to be part of a trilogy, the Melrose Mysteries. The next in the series is completed but unpublished and the final one was a work in progress.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was perhaps inevitable that he would continue to write: he was known for his fluency with words and his impressive command of the English language – he could lecture seamlessly without notes for precisely an hour, timed to perfection – and was an absolute stickler for the correct use of language and grammar.

An immensely practical man, he also loved skills, such as cabinet-making and carving, that entailed using his hands: he could restore old porcelain; create furniture or build a stone fireplace; design and sew clothes or loose covers, cook and garden. But his two greatest pleasures were painting and working with wood.

Having travelled widely, he was particularly fond of Germany and Austria, whose scenes he captured in sketches or paintings, including a series of botanical watercolours of wild flowers he had seen in the alpine meadows. His greatest creation, however, was a harpsichord that he built from scratch, following the specifications and plans of an 18th-century French instrument held in Edinburgh University’s Russell Collection of old keyboard instruments.

It was a real labour of love that took years to complete but was a perfect example of his patience, attention to detail and determination to get things right.

Mutch, who was also passionate about history and one of the founders of Edinburgh’s Cramond Heritage Trust, was interred in the kirkyard of Cramond Church, which he had served as an elder for 45 years.

Widowed in 2010, he lived latterly in Newton Stewart, among the thickly forested hills of Galloway, with his daughter Sheila, who survives him.