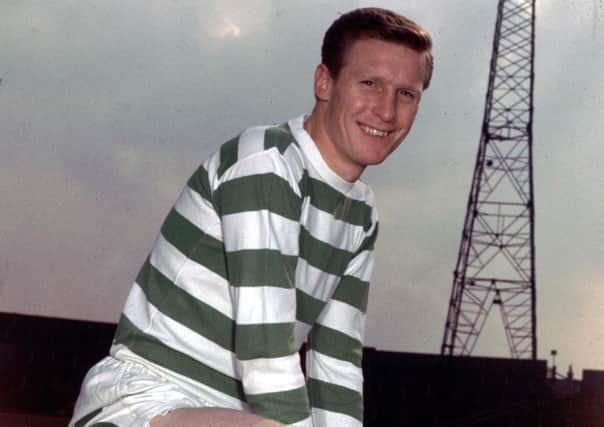

Obituary: William ‘Billy’ McNeill, Celtic footballing legend, leader of the Lisbon Lions, Scottish internationalist

A bad year for Scottish football got worse on Tuesday, with the news that Billy McNeill, the greatest Celtic player and a true legend of the game, had lost his long and public battle with dementia.

The image of McNeill, standing on the balcony in Lisbon’s National Stadium, holding aloft the newly minted European Cup is one of the iconic football ones. It has been replicated in bronze in front of Celtic Park, capturing as it does the greatest moment in the near 150-year history of Scotland and the Beautiful Game.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcNeill’s club career is the stuff of legend. Born in Bellshill, the son of an Army PTO, he – apart from a short spell in England, where he went to a rugby-playing school – was a commanding centre half throughout his six years at Motherwell’s Our Lady’s High School.

He won Scotland Under-18 schoolboy honours, and his performance in a 3-0 win over England at Celtic Park in 1957, according to legend, forced the watching Jock Stein to tell Chairman Sir Robert Kelly: “We must get that boy to the club.”

McNeill needed little persuading. He left school, worked briefly for Lanarkshire County Council, then for Stenhouse, the insurance brokers, but, still a part-timer, he made his first-team debut against Clyde in August 1958. Celtic won.

He had to wait for his turn, since Bobby Evans was the incumbent Celtic and Scotland centre-half. However, Evans’ transfer to Chelsea in 1960 saw McNeill take over. He was still a part-timer, as he would continue to be until, after a successful apprenticeship via the Under-23 and Scottish League teams, he made his Scotland debut, in the notorious 9-3 Wembley loss to England in 1961.

McNeill emerged from that disaster with some credit, but, in what was to be a feature of his career, he never replicated at international level the success he would enjoy at his club. He only won 29 caps over an 11-year period, only led Scotland eight times, and was never the automatic choice for his country he was at club level.

Certainly, some injuries restricted his international appearances, but, at a time when the central defensive partnership of McNeill and John Clark at Celtic was recognised as just about the best in the business, they were only ever picked together once, in a 2-0 defeat to USSR in 1967.

The Celtic team which McNeill broke into was long on promise, short on silverware, and it was not until Stein was brought back as manager in February, 1965, that the club’s fortunes turned. This was a fortuitous move for McNeill, who, disappointed at the way the club was stagnating, was contemplaing asking for a transfer.

Stein’s return altered the Scottish football landscape totally and it was a towering McNeill header which secured a 3-2 Scottish Cup final victory over Dunfermline in 1965, ending the club’s near eight year trophy drought and signalling the start of something special.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA League and League Cup double in 1966 demonstrated how the Stein revolution had changed things, but, Scottish football had not seen anything yet. In 1967 Celtic won every competition they entered, their season capped with that iconic image of McNeill holding aloft the European Cup, after holders Inter Milan had been totally crushed. The result might have been 2-1, the reality was, Celtic won by a mile. The legend of the Lisbon Lions was born.

The following years brought fantastic success, nine league wins in a row, other cup successes. In all, McNeill would go on – before he quit at the top – his last act as a footballer was to lift the Scottish Cup following victory over Airdrie in 1975 – to lift a then record 23 trophies as Celtic captain.

He retired, after 789 games for the club, all those trophies and medals, a Footballer of the Year award and an MBE for his services to the game.

He took a break for some 18 months, concentrating on a burgeoning business portfolio, but Clyde persuaded him to return to the game as manager and a record of four wins and three draws in eight games as a manager, saw him lured to Aberdeen in 1977 to follow Ally MacLeod, who had become the Scotland manager.

At Pittodrie, he won the League Cup, and gave Jock Wallace’s treble-winning side a terrific run for their money. He had proved himself a more than competent manager, so, when the strained relationship between Stein and the Four Families who ran Celtic finally snapped and Stein was eased out of the door, the board turned to McNeill to continue his mentor’s great work at the club.

Stein had survived 13 years of the machinations of the families, McNeill stood it for five. He turned also-rans into champions in one season, then won the Scottish Cup, then back-to-back league titles, before, in 1983, failing by one point to make it three titles in a row.

By then, however, McNeill had had enough of the board and, when the men upstairs offloaded Charlie Nicholas to Arsenal, McNeill too quit for England, and Manchester City.

City back then were the very-poor relations in Mancunian football, languishing in England’s second tier. It took him two seasons, but McNeill got them back into the top flight, but, as at Celtic, he faced boardroom interference, and quit to join Aston Villa in 1986. This was not perhaps Billy’s best move, since, at the end of that season, he had the unique distinction of having managed two of the relegated sides, as Villa and City both went down.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPeter Swales, his chairman at Manchester City, perhaps best summed-up the situation McNeill found himself in England, when he said: “If ever a man was made for one club, it was Billy McNeill and Celtic; his heart was always at Parkhead.”

To Celtic he returned. His successor, Davie Hay, had also had a difficult relationship with the men at the top of the club and when, in 1987, Celtic failed to defend the league title they had won so-memorably on the final day of the previous season, Hay was out and McNeill returned for a second spell at the club he loved.

He presided over a Centenary Year league and cup double in 1988, but, in addition to his travails with the four families on the board, McNeill also had his battles with chief executive Terry Cassidy before, in 1991, he walked away from the Celtic job.

He concentrated on his growing family and his business interests. McNeill’s, his south-side pub was a place of pilgrimage to Celtic fans. He wrote a trenchant newspaper column, had a brief spell as director of football and caretaker manager at Hibs, but his rapprochment with Celtic was healed by the arrival of Fergus McCann.

McNeill and the Lisbon Lions were given their due place in Celtic history, the captain took on a Club Ambassador’s role in 2009 and everything seemed set fair for his old age.

Then came the devastating news: dementia, that dreadful disease which seems to feast off former footballers, had taken Billy McNeill. His illness became public knowledge in 2015.

Celtic had to act. A statue of McNeill, in that legendary pose, holding aloft the European Cup, was commissioned and sited at Parkhead. The Celtic family, and the wider football community held its breath, Billy fought with all his amazing courage, but, on Tuesday morning came the news everyone had dreaded – he had lost his battle.

Wife Liz – they were one of football’s most-gilded and loved couples – daughters Susan, twins Carol and Libby, Paula and son Martyn, have lost a loving and devoted father. Billy’s grand-children have lost a doting and much-loved Papa.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe surviving Lions have lost the leader of their pride, the Celtic family has lost one of its icons. In his early days at the club, because he was one of the few players who owned a car, McNeill was dubbed “Cesar” by his team mates. The name came from actor Cesar Romero, who had played the getaway driver in the original version of Ocean’s Eleven.

After seeing him with the European Cup in Lisbon, Bertie Auld decided: henceforth Billy would be Cesar, because he looked like a Roman God as he held aloft the giant cup.

As we prepare to bury Cesar, we should praise him. Billy McNeill MBE, with his honorary Doctorate from Glasgow University and his place in the Scottish Football Hall of Fame, was not just the greatest Celt, he was one of the all-time greats of Scottish football.

MATTHEW VALLANCE