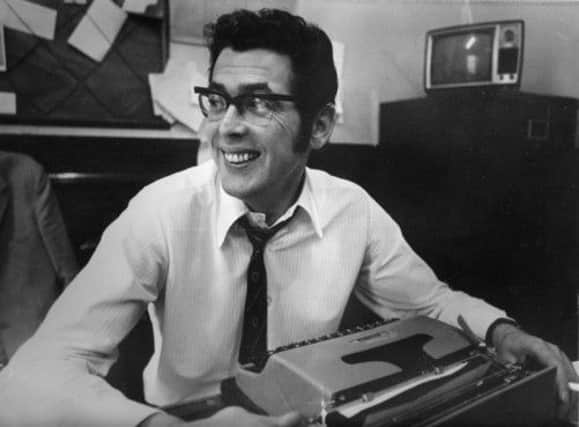

Obituary: Ted Kidd, journalist

Ted Kidd, the doyen of the press corps in Aberdeen, was a journalist of the old school; he described his job as giving him “a ringside view of life”.

Long-time staffer on the Daily Record, he was the only journalist to cover every day of Lord Cullen’s marathon 180-day inquiry into the causes of the Piper Alpha disaster.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe reported on major stories such as the mystery of the loss of the Aberdeen trawler Blue Crusader; the 1964 typhoid epidemic when Aberdeen became a closed city; the killer collapse of the eight-storey partially built Aberdeen University zoology building; the breakouts of safeblower Johnny Ramensky from supposedly escape-proof Peterhead Prison; the double loss of lifeboats from Longhope in 1969, and Fraserburgh eight months later; and the execution of Henry Burnett 50 years ago this month, when, on 15 August, 1963, Burnett was the last person to be hanged in Scotland.

Kidd was outside Craiginches Prison that day, having earlier gained an inside track on preparations for the execution from one of his numerous contacts.

It was Peterhead Prison which provided the backdrop to one of his more memorable exploits, when, in 1976, Paddy Meehan, the safecracker wrongly convicted of the murder of 72-year-old Rachel Ross in Ayr seven years before, was granted a Royal Pardon.

The Record bought up Meehan’s story before his release from the grim North-east jail, and as he took his first steps from the prison gate, he was roared off to freedom by Aberdeen lawyer David Burnside.

Kidd’s job was to fend off pursuing cars from rival papers – and in an incident worthy of a stock-car stadium, he was rammed from behind by rival Ian Rennie from the Scottish Daily Express. But Kidd’s driving dexterity won out, and the chasing pack were held at bay long enough for Meehan to vanish to the secret Record hide-out.

Those were days before mobile phones, when releases from Peterhead caused the hacks to race south towards Aberdeen to secure use of the first telephone box near the village of Stirlinghill to phone the story over.

An apocryphal tale is that Kidd had a contact who worked for Post Office Telephones, and who quietly gave him a special key, explaining that behind each phone kiosk was a lock with which the phone could be turned off.

So prior to the next Peterhead incident, Kidd stopped at the box, and switched it off with his master key. He arrived back at the box to find it surrounded by angry hacks, about to press south to find the next working phone kiosk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKidd quietly waited until they departed, slipped round the back, and turned on the phone line again.

Edward Kidd was born the son of a farm servant in a cottar hoose in the heartland of Buchan, and had his early education at the long-vanished school at Auchiries, near Cruden Bay.

National Service with the RAF brought his unwavering memory to the fore when as the only clerk in the motor pool of RAF Nicosia, he maintained complete track of 314 vehicles and their registration numbers.

Back home in 1956 and entertaining notions of a career as a novelist, Kidd discovered newspapers. This was a time when every major newspaper in the land existed in Aberdeen – Scottish Daily Express, Scottish Daily Mail, Daily Record, The Scotsman, The Glasgow Herald, and the Daily Herald, forerunner of The Sun – plus freelances, stringers, BBC Radio, two television stations and all the national Sunday newspapers.

Kidd’s break came through DC Thomson, working from its Exchange Street office by the Tivoli Theatre, and covering for a range of daily, evening, weekly and Sunday outlets.

In cutting his teeth as “county man” with the long-dead weekly The People’s Journal, he quartered the counties of Aberdeen, Banff and Kincardine, finding offbeat and human interest stories, and filling a nascent contacts book.

When in 1968, five years after Kidd had joined the Daily Record team working out of large premises fronting Union Street, his talents saw him “minding” Trudy Birse, a vital witness in the sensational murder trial of Sheila Garvie and her lover Brian Tevendale of the playboy “flying farmer” Maxwell Garvie.

There was world coverage of the trial in Aberdeen, the public queued from early hours to secure places in the public gallery and newspaper sales soared.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis proved to be a golden era of journalism, when resources were plentiful, news desks threw money at a good story, and plain old-fashioned initiative was the basic ingredient in delivering that story.

Self-effacing and a born raconteur, Ted’s secret as a successful journalist wasn’t complicated – a gentle smile and an ability to forge a connection with whomever he spoke adeptly drew out essential facts from the most reluctant of sources. Or as he himself would say: “I am but a winged messenger of the truth.”

Ted served news and newspapers for an astonishing 55 years, latterly covering local government. His outstanding service to journalism in the Granite City was recognised in 2011 when Lord Provost Peter Stephen organised a reception in his honour, an event crowded out by representatives of Aberdeen’s hack pack.

In true press fashion, behind the deservedly fine tributes honouring a genuine gentleman of journalism lay the reality that before council meetings, Ted would fortify himself with two Aiberdeen butteries liberally pasted together with marmalade.

Mr Kidd died peacefully at home after a short illness, and is survived by his partner Chris, and by his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.