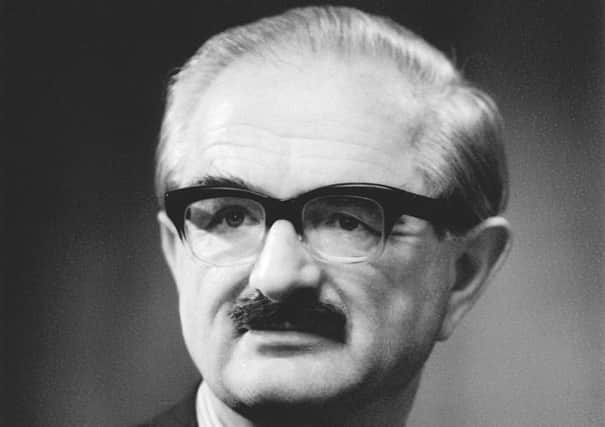

Obituary: Sir Arthur Bonsall, codebreaker and civil servant

Sir Arthur Bonsall spent almost 40 years operating in the shadows, working at the secretive Bletchley Park during the Second World War deciphering German Luftwaffe movements, and later headed four of the most important divisions of the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) at a critical time in the 1950s and 1960s, during the Cold War and a succession of world crises, including Suez, the Soviet invasion of Hungary and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Bonsall was then appointed head of GCHQ in 1973.

During the war, Bonsall was heavily involved in intercepting and decoding the Luftwaffe’s activities, positions and tactics, which helped the RAF enormously during the Battle of Britain, the Blitz, Allied strategic bombing raids on Germany from 1942 onwards and D-Day in 1944.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike many of his colleagues, Bonsall had been indoctrinated to believe that signing the Official Secrets Act was for life, and subsequently he never spoke about his war-time work, not even to family. This, however, changed when GCHQ moved to its new building on the outskirts of Cheltenham and an era of increased “openness” was ushered in. A man of utmost discretion, Bonsall acknowledged that he found it “contradictory and shocking to see buses with the four-letter acronym” emblazoned on them.

He recalled the necessity for absolute security and the importance of discretion even within Bletchley itself: “Do not talk at meals. Do not talk in the transport. Do not talk travelling. Do not talk in the billet. Do not talk by your own fireside. Be careful even in your Hut…”

He added: “Grandchildren now had authority to ask me what I was doing, so I began to have to try to remember what I did do during the war. That was quite a big change.” Some colleagues, however, remained silent and took their work to the grave.

Born in Middlesbrough in 1917, Arthur Wilfred “Bill” Bonsall was the son of Wilfred and Sarah. When he was six, the family moved south to Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire. He attended Bishop’s Stortford College before reading Russian, French and German at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge. Upon graduation in the summer of 1939, Bonsall was assessed as unfit for military service.

While at Cambridge, he was talent-spotted for sensitive linguistic work by the proctor of St John’s College, Martin Charlesworth. Called for interview with another student in October 1939 at Charlesworth’s rooms, with Alastair Denniston, head of the Government Code & Cypher School (GC&CS, Bletchley) and cryptanalyst John Tiltman, the two young men were asked if they were interested in “confidential war work”. They replied “Yes”.

Weeks later, Bonsall received a letter instructing him to travel on New Year’s Eve to Bletchley Junction where he would be met. He recalled he had been told to tell “nobody, not even my parents, where I was going”. He arrived and, after being taken to the Mansion and signing the Official Secrets Act, began work the next day. He was initially assigned to a hut to work on German Luftwaffe traffic, in particular their low level tactical codes and radio traffic. “Within minutes,” he said, “he was seated at a trestle table copying out coded messages onto large sheets of paper.” He tracked German bombers and those planes flying from France to attack targets in Britain and their subsequent return routes.

Thanks to this work, Bonsall’s reports highlighted the Luftwaffe’s objectives and were invaluable to the RAF. Further work contributed to the breaking of other German codes. He also first proposed the use of aircraft equipped with radios to fly over German territory monitoring the Luftwaffe air defence communications. Such “spy planes” played a key role in the Cold War, and continue to do so today.

As the war drew to its conclusion, in late 1944, Bonsall transferred to an ultra-secret MI6/Bletchley Park team which was breaking Soviet codes and ciphers in an innocuous central London house.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWithin, the teams intercepted the internal teleprinter systems of leading Soviet military and Communist Party officials; it was so secret that it was kept under the control of MI6 and, until 1948, completely separate from GCHQ, who then took over its running.

Post-war, Bonsall moved swiftly up the hierarchy and, between 1952 and 1962, directed, in turn, the four major divisions at GCHQ, being responsible for station operations, intelligence production and policy. He oversaw the intercepting of Soviet communications with Warsaw Pact countries and the 1956 invasion of Hungry, before covering the Middle East following the Suez Crisis.

He then spent a year at the Imperial Defence College before returning to GCHQ as a superintending director of intelligence and member of the board. In 1973 he became the sixth director of GCHQ. “In those days one didn’t apply for a promotion, one hoped for a recommendation,” Bonsall said. “I was recommended by my predecessor Joe Hooper. In a sense it was what I had been hoping for some time.”

However, one of his first tasks was to fly to Washington to smooth diplomatic relations between the two countries, following prime minister Edward Heath’s refusal to allow US president Richard Nixon’s administration to use GCHQ’s listening station and air base in Cyprus during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Henry Kissinger, the national security adviser, ordered the US National Security Agency (NSA) to suspend intelligence co-operation with GCHQ. Fortunately, NSA officials informed Kissinger that intelligence exchanges were bound by law and a then secret legal agreement forbidding any curtailment.

During his tenure as director, Bonsall was responsible for rationalising GCHQ’s collection sites. He also oversaw the continued monitoring of Communist Moscow and its satellite states, as well as the increasing tensions in the Middle East and the threat of terrorism from the IRA.

Upon leaving GCHQ in 1978, Bonsall served as a tax commissioner for a while, before retiring completely. Thereafter, he became more interested in speaking about the work of Bletchley Park; he eventually produced two monographs on the work of the Air Section. He was appointed CBE in 1957 and KCMG in 1977.

In 1940 he met Joan Wingfield, recruited in 1937 to Bletchley’s Italian Naval Section. They married in 1941. She died in 1990. He is survived by their four sons and three daughters.