Obituary: Ron Hall, investigative journalist

RON Hall virtually invented the art of investigative journalism in Britain, when, as one of a trio of young reporters in the 1960s, he created the Insight team on the Sunday Times.

He and his partners, Jeremy Wallington and Clive Irving, had been recruited by Sir Denis Hamilton, then the paper’s editor, with the brief to come up, every Sunday, with a digest of the week’s news, adding some analysis at the end.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut shortly after they arrived at the paper, the scandal of the Profumo affair broke, and they began to produce, week after week, a detailed account of what had happened, digging ever deeper into the background of the story.

Hall was the intellectual driving force behind the concept. He would suggest an atmospheric opening paragraph, leading into a story full of colour and detail, which would add context and background to what had already appeared in the daily press.

Shortly after that, Hall’s contacts with a famous property developer of the day, Benny Gray, put him on to another exposure, this time of a property racket in London.

Peter Rachman, who owned numerous flats in Paddington, was using ruthless and bullying tactics to drive out tenants so that he could sell on to more lucrative clients. Insight broke the story, named the guilty man, and Rachmanism, a term coined by Hall, entered the English vocabulary.

His definition of good journalism was simple: “You can’t write a story if you don’t understand it.”

In the course of his 20 years on the paper, he was associated with some of its most important investigative stories, including the Philby spy scandal, thalidomide, and the remarkable disclosure that the yachtsman Donald Crowhurst, who had taken part in a round-the-world race, had faked his journey, pretending to have circumnavigated the globe, when in reality he had never even rounded the Horn. He wrote a book about it with a colleague, Nicholas Tomalin. Hall had earlier turned the Profumo affair into a book, called Scandal 63.

The Insight style became much copied, and occasionally caricatured. A typical intro would run: “At 11.30 precisely, a steel-grey Mercedes 150 SL screeched to a halt outside the MI6 building in central London, and a small, squat figure emerged, a Havana cigar clenched between his teeth…” Hall himself was among the first to mock it, but at the time it was groundbreaking.

He was also a good manager of other journalists; recruiting promising young talent and nurturing their careers. The feature writer and author, Lynn Barber, said later: “I owe him my career.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRonald Hall was born and brought up in Sheffield, the son of a builder from whom he inherited a lifelong love of craftsmanship, becoming, himself, a skilled carpenter.

He went to the local grammar school, Dronfield, where he was head boy and his first wife Ruth was head girl. Hall went on to Pembroke College at Cambridge University, where he studied mathematics and statistics. His career took shape on the Daily Mirror, where he was one of the “Old Codgers” on the paper’s letters column. He left to found a weekly news magazine called Topic with Wallington and Irving, joining the Sunday Times in 1962 when the magazine folded.

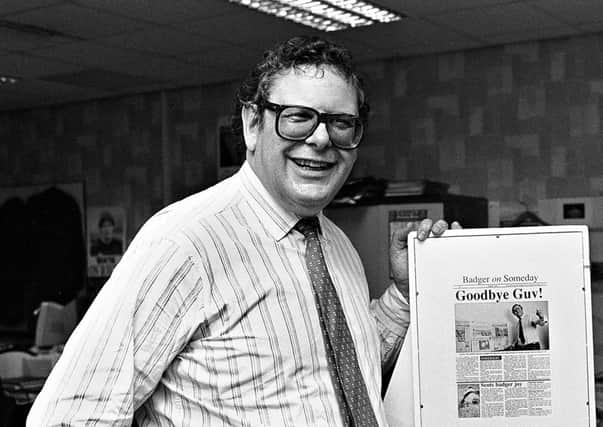

At the paper, he not only became a guiding influence, but a legend in his own time, a grumpy but companionable presence, awarded the title “Badger Hall” by Private Eye, possibly because he used to work through the night.

His comments became legendary. He would describe any run-of-the-mill story as “Beta Minus.” On being asked by his editor Harry Evans (later Sir Harold) if he had read a particular manuscript, he would limit himself to: “I’ve looked at it.”

A worthy tome, coming into the office, would be given “the two-page test,” and, when accused of running a particularly lengthy piece unlikely to attract many readers, he commented: “Never underestimate the value of unread copy.”

He and Ruth bought a coach house at the back of a mansion in Hampstead, employing the then-little known architect Norman Foster to design a state-of-the-art modern dwelling. Hall built much of it himself and did all the carpentry. Ruth was a talented pianist and Hall developed a passion for classical music. He became friends with many leading musicians, who were regular visitors to the house, which he equipped with the latest sound technology.

Hall’s tenure at the Sunday Times, where he was, successively, features editor, magazine editor, and deputy editor, came to an end in 1982 after the paper was bought by Rupert Murdoch.

He joined the Sunday Express, where he edited the magazine, then was recruited to be associate editor of the short-lived London Daily News, where he designed the paper.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter working as a consultant editor on Scotland on Sunday, he was invited by his old colleague Clive Irving to be London editor of Condé Nast’s Traveler magazine, where he memorably compiled a 13,000-word report on 50 Greek islands, collecting sand samples from each. It is still described as the most successful issue of the magazine, and sold out all over the world.

In 1981, Ruth died after a short illness at the age of 48, and a year later Hall married Christine Walker, who had been his secretary at the Sunday Times and was later its travel editor. The marriage was dissolved in 2002 and he began a relationship with Pat Glossop, a research editor on Traveler. They married in 2008.

An inveterate traveller himself, keen tennis player (he once boasted that he had taken a set off Roger Taylor) and lover of fine wine, he had a wide circle of friends.

His former editor Sir Harold Evans says that he “drew the warm affection and admiration of an eclectic range of friends, a magical circle who shared his taste for wine and gossip as well as his passion for journalism that mattered.”

The last ten years of his life were blighted, however, by Parkinson’s Disease, which developed into the more serious Parkinson’s Lewy bodies – protein build-up in nerve cells.

He died of pneumonia in London’s Royal Free Hospital, attended by his last two wives. He did not have any children.