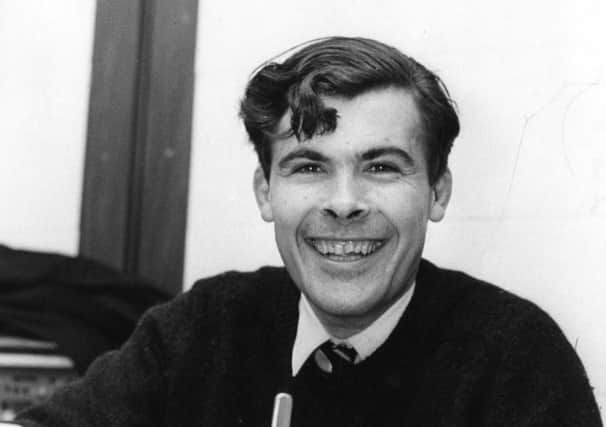

Obituary: Philip Howard, journalist

The distinguished and erudite journalist, Philip Howard, was for more than 50 years a central figure at The Times. He joined in the days when the paper was known as The Thunderer under William Haley and its articles and leaders were hugely influential. In his career, Howard was a leader writer and the literary editor while also contributing informed columns as philology, grammar, house style, manners and etiquette.

In the official History of The Times Howard commands a special place. He was described as, “a Times man of the choicest vintage”. He was remembered by colleagues with much affection for his style, exuberance and sense of humour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHoward did spend much of his career in the south but he had close connections with Scotland. He did his national service with the Black Watch (1956-58) and was motor transport officer – not an entirely suitable position as Howard did not drive. He loved army life and was a popular figure in the Black Watch – he remained proud of his connection with the regiment and the friends he made there.

He often attended regimental dinners, despite his dinner suit being somewhat old and scruffy. It caused some annual amusement to the Queen Mother, the regiment’s Colonel-in-Chief, who would invariably raise an eyebrow at the state of his tie.

In 1968 he published his first book, Black Watch, a subject close to his heart.

His Scottish connection went further. His first job as a journalist was with The Glasgow Herald in 1959. Howard was put on a year’s trial as a general reporter. “I was given the accidents – going round in a car at night looking for crashes. I was never very good at that. At my first crash I saw a man decapitated and threw up, much to the delight of the Glasgow journalists, who are very tough.”

He remained in Glasgow until 1964 and acted in a wide variety of capacities – from being the paper’s political diarist and literary editor to a sports journalist covering women’s lacrosse.

Philip Nicholas Charles Howard was the son of an English international rugby player who was capped eight times in the early 1930. His mother, Doris Metaxa, won the Ladies’ doubles at Wimbledon in 1932.

Howard attended Eton, where he was a King’s Scholar and read classics at Trinity College, Oxford, gaining a first in Classics. In 1959 he married Myrtle Houldsworth, the daughter of Sir Reginald Houldsworth, a baronet who resided near Maybole in Ayrshire.

Howard joined The Times in 1964 and soon proved himself an exceptional wordsmith who could cover numerous subjects. He delighted in describing himself modestly as a “simple hack” but Howard was a consummate and professional journalist throughout his career.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was recognised as one of the characters in the newsroom and had an ability to lighten the atmosphere, even on the most frantic days, with his glorious guffaw. One of his editors, Sir Peter Stothard, described Howard as “part Bohemian man of letters, part Scots puritan gent”.

Many Times readers will recall the pleasure his column, Lost Words, which livened up many a Saturday breakfast with its explanations of esoteric and obscure words.

Howard loved the English language but was no purist. He welcomed new definitions and usages of words or phrases. “Language,” Howard wrote, “is the only absolutely true democracy. It’s not what professors of linguistics say, but what people do. If children in the playground start using ‘wicked’ to mean terrific then that has a big effect.”

Howard wrote more than 20 books including collections of his Lost Words. He had written on manners and advised on etiquette for many years. Howard was asked if it was proper to thank someone by e-mail for a Christmas present. “In modern manners, for those who don’t have good handwriting, it’s OK to thank for your presents by e-mail – provided you do it by Boxing Day with warmth and, if possible, a joke.”

Other publications included The British Monarchy, The Royal Palaces and Weasel Words.

Howard retained his wife’s connection with Ayrshire by maintaining a cottage in the area and much enjoyed walking the Scottish countryside all his life. He was a keen member of the Garrick Club and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He also listed his recreations as, “Jack Russells and the Stand at Twickenham”.

His wife died earlier this year and he is survived by their two sons and a daughter.

ALASDAIR STEVEN