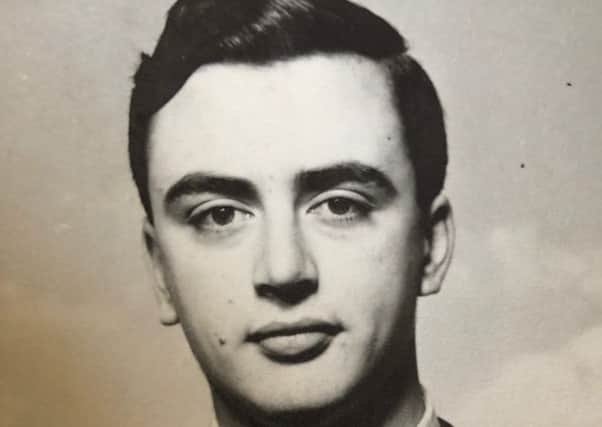

Obituary: Paul Addison, internationally-noted historian and biographer of Winston Churchill

Paul Addison, who died on 21 January after a long illness bravely endured, was without doubt one of the finest historians of his generation. His immense body of published work commands international respect and his studies on the impact of the Second World War, as well the role of Winston Churchill, remain unsurpassed for their insight and sheer readability.

Paul was born in 1943 in Wittington, Staffordshire. He never knew his father, an American soldier stationed locally, but he was baptised in the chapel of a US army camp nearby. He was brought up by his mother, Pauline, with help from her parents, and educated in the village school in Wittington, before going on to King Edward the Sixth Grammar School and Pembroke College in Oxford.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe took a First there in 1964 and from 1965 to 1967 he was a research student at Nuffield College, helping Randolph Churchill prepare the papers of his father Winston for publication. Two other fine scholars worked with Paul on this project, Martin Gilbert and Cameron Hazlehurst.

AJP Taylor was one of Paul’s teachers and his eccentric brilliance in the seminar room and on paper had a profound influence. Taylor believed that history should reach the widest possible audience and this was a view from which Paul never departed in his own writing and teaching. In 1967 he took up an appointment at Edinburgh University where the superb quality of his teaching is still remembered. In 1975, his first and groundbreaking book, The Road to 1945, came out. This obituarist was short of cash at the time and sold a suit to Armstrong’s, now trading in the Grassmarket, to raise the £6/10- the book cost. It was worth every penny and has never been out of print since, setting a new standard for the analysis of the social, cultural and political forces behind Labour’s great 1945 election victory.

Many more books and articles followed, for once Paul started writing he seemed able to make the words flow like a burn. One of his books, Churchill on the Home Front (1992), concentrated on a figure who had begun to fascinate him, but he also saw the need for informed and open debate rather than hagiography – Paul had no time for some of the simplistic vilification of Churchill that crept into this debate. He saw Churchill as someone of volcanic energy and true courage, though unable to shake off the prejudices of the era which had formed him.

In 2005, he wrote what is perhaps the best short biography of Churchill, an enlargement of a 30,000 word entry he had written for the new Dictionary of National Biography. Paul’s final words in this book were that “Churchill is no longer the hero that he used to be, but in the end the recognition of his frailties and flaws has worked in his favour. It has brought him up to date by making him into the kind of hero our disenchanted culture can accept and admire: a hero with feet of clay”.

By then Paul had left Edinburgh University’s History School – in 1996 he had been made director of its Centre of Second World War Studies. He worked productively there with his younger colleague and friend Dr Jeremy Crang and some notable conferences and related materials were among the results.

In retirement, Paul’s output continued, much of it in collaboration with Jeremy on the key role of propaganda, information and the state’s monitoring of civilian morale during the war. Their expertise was drawn upon by the makers of a recent and very fine television documentary series on the Blitz. Their latest book, The Spirit of the Blitz, will come out later this year.

Paul wore his scholarship lightly. In company he was as unassuming as he was genial and amusing. He had an infectious laugh and could readily make others laugh. He once said that inside most of us there is a Ken Dodd struggling to get out. With Paul he frequently did.

This was evident at Open University summer schools, which Paul loved joining as a hugely popular guest lecturer. He enjoyed an easy camaraderie with a student body of a wide and varied social mix. He later became a much-loved president of the Open University History Society, now the Open History Society, which meets regularly in Edinburgh. He chaired many of its meetings and Christmas lunches with erudition and affectionate bonhomie.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis was a full life but there was always abundant room in it for Rosy, whom he married in 1979. Paul was quietly proud of her and their sons James and Michael. They were all there with him at the end.

Paul’s was a life well lived, one of well-earned academic distinction but also defined by his capacity for friendship, his warmth and his decency. There are all too many of us who will miss him deeply – a short tribute from former student the Rt Hon Gordon Brown will be read at his funeral – but we can still raise a parting glass to him.

Ian S Wood