Obituary: Nelson Mandela, former South African president

Mandela achieved a cult status of almost mythic proportions, comparable to the Pope, Pele and a reincarnated Elvis Presley rolled into one. He became a symbol of hope for human relations and reconciliation worldwide. His singular commitment to personal and national redemption lent him the aura of a saint, a Messiah figure, something he himself scoffed at. “One issue that deeply worried me in prison was the false image I unwittingly projected to the outside world of being regarded as a saint,” he wrote in one book. “I never was one, even on the basis of an earthly definition of a saint as a sinner who keeps trying.”

However, the fact that he also had real human frailties and shortcomings, on his own admissions, made him a greater man than was grasped by hagiographers and those who believed only the legend and could not see through the fog of adulation. His first two marriages failed spectacularly, but he seemed to achieve happiness when, at the age of 80, he married his third wife, Graça. All in all, Mandela’s iconography projects an ordinary man with ordinary weaknesses who was nevertheless capable of magnificent courage, compassionate generosity and, at certain critical points in history, imaginative and virtuous acts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen he became State President he rubbed shoulders with and took big donations from some very dubious statesmen, including Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, Cuba’s Fidel Castro and Indonesia’s President Suharto. It was Suharto who gave Mandela the first of the loose and colourful tunic-like shirts that became the South African’s own unique fashion statement.

The Mandela story might have ended abruptly, and with less acclaim, in 1964. In early June of that year Mandela, then aged 45 scribbled some brief notes in his cell as he prepared to be hanged by the neck after being convicted of sabotage and planning guerrilla warfare against South Africa’s apartheid state - offences that carried the death penalty under the 1962 Sabotage Bill. His jottings, which were preserved, outlined a defiant statement he planned to make in Pretoria’s Palace of Justice before he was taken to Death Row.

Mandela was unable, decades later, to decipher everything on that scrap of paper, but he said those parts he could read made clear that he had no intention of appealing to the presiding Judge, Quartus de Wet, for mercy. One scrawled sentence reads: “I meant everything I said” - a reference to his closing statement from the dock just a few weeks earlier. That speech, lasting more than four hours on 20 April 1964, was the most effective of Mandela’s whole political career. It identified him clearly as the leader not just of the ANC (African National Congress), the main African movement resisting the injustice of apartheid, but of the entire multi-racial opposition to racial separation and discrimination. His words reverberated around the world, providing a manifesto for anti-apartheid campaigners everywhere.

From the dock Mandela had explained to the scarlet-robed Judge de Wet his political ideals and admitted he was the leader of Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), the infant guerrilla wing of the outlawed ANC. Mandela said that in the half century before Umkhonto was born the ANC had been committed to non-violence in the struggle for black freedom. But, he said: “The hard facts were that fifty years of non-violence had brought the African people nothing but more repressive legislation, and fewer and fewer rights.”

Mandela, accused by state prosecutor Percy Yutar of being a communist, denied it. “From my reading of Marxist literature, I have gained the impression that communists regard the parliamentary system of the West as undemocratic and reactionary,” he said. “But, on the contrary, I am an admirer of such a system ... I regard the British Parliament as the most democratic institution in the world, and the independence and impartiality of its judiciary never fail to arouse my admiration.”

During the trial, Mandela recalled that one remand prison guard taunted him as the lights went out at night: “Mandela, you don’t have to worry about sleep. You are going to sleep for a long, long time.”

However, in November 2012, when Mandela was past his 94th birthday and his intellectual powers were declining fast, private papers from archives at the University of Cape Town showed thatMandela joined the South African Communist Party at about the time of the Sharpeville Massacre on 21 March 1960 when South African police shot dead 69 people at a demonstration protesting against the pass laws that were one of the fundamental building blocks of legislation enforcing racial segregation. The discovery by Stephen Ellis, Desmond Tutu Professor of Social Sciences at the Universities of Amsterdam and Leiden and former editor of Africa Confidential, confirmed numerous historical assertions by leading members of the South African Communist Party and by party minutes that Mandela, despite, his denials, had long been one of their number.

The editor of the South African History project at Johannesburg’s University of the Witwatersrand argued that the revelation that Mandela was a prominent Communist Party member does not detract from his historic stature, but went on: “It does, however, mean that the version of history propagated by the ANC, which has governed South Africa since 1994, is seriously flawed.” That mirrored an earlier observation by one of South Africa’s most penetrating analysts, the late Frederik van Zyl Slabbert, who said: “One thing the ‘old’ [apartheid] South Africa and the ‘new’ [post-apartheid] South Africa have in common is a passion for inventing history.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough Mandela appears to have joined the Communist Party more for its political connections than its ideas, his membership could have damaged his standing in the West had it been disclosed. Africa was a Cold War proxy battleground until the end of the 1980s, and international support for his cause drew partly on his image as a compromise figure loyal neither to East nor West.

Mandela, in his April 1964 speech from the dock, also said Africans only wanted security, a stake in South African society and equal political rights. “It is a struggle for the right to live. I know this sounds revolutionary to the whites in this country, because the majority of voters will be Africans. This makes the white man fear democracy.”

Mandela’s rough private notes, as he anticipated the gallows, said: “If I must die, let me declare for all to know that I will meet my fate like a man.” They reflected the final sentences he had uttered in his statement from the dock, words which were banned from publication under apartheid law but which nevertheless became renowned:

During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this

struggle of the African people. I have fought against white

domination, and I have fought against black domination. I

have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society

in which all persons live together in harmony and with

equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for

and achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am

prepared to die.

When Mandela completed his statement from the dock, Judge de Wet adjourned for three weeks to consider his verdict. On return, he pronounced Mandela guilty but said he would take more time to reflect on whether or not the prisoner would hang. Twenty-four hours later Judge de Wet said that, since Mandela’s sabotage campaign had not progressed beyond the planning stage, he had decided to show leniency. Mandela would not be executed. He would go to prison for life.

Even so, Mandela’s career and his subsequent ascent to eminence might have ended there and then. For most of his prison years he was more or less a non-person as far as the outside world was concerned. He could not be quoted in South Africa and his picture could not be shown. There was nothing to guarantee he would become a legend in his own lifetime, perhaps the last major iconic figure in a world increasingly distrustful of political ambition. Little was heard of Mandela for many years as he broke rocks, his hands becoming calloused from pick and shovel work, as he broke rocks on his Robben Island prison in cold waters five miles off the Cape coast. He was allowed only 30 minute visits – once every six months. When his mother died in 1968 and his eldest son, Thembekile, was killed a year later in a car crash, his jailers refused him permission to attend their funerals. These refusals might have been enough to bury him in bitterness for ever. Yet, in time, he transcended most of his resentments.

* * *

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born on 18 July 1918 as the First World War ended and the Bolshevik Revolution was being consolidated. His mother, Nosekeni Fanny, was the third of four wives of Gadla Henry Mandela, a chief deposed for insubordination by British administrators who confiscated most of his income, cattle and land. Gadla was an illiterate but intelligent man, a leading custodian of the oral history of the Xhosa people, South Africa’s biggest tribe, and a senior adviser to the king of the Tembu clan of the Xhosas. Through Nosekeni, titled the Right Hand wife, and Gadla’s three other wives - the Great Wife, the Left Hand wife and the Iqadi (or support house) wife - Nelson had eight sisters and four brothers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGadla died in 1927 when Nelson was aged nine. His mother took him to the Tembu royal palace where he was subsequently brought up by David Dalindyebo, Regent to the infant Tembu king, Sabata. The palace, known as the Great Place, was, in fact, a modest affair - two Western-style, tin-roofed houses surrounded by small thatched roof rondavels. But to the young Mandela it seemed like the very centre of the world, compared to the humble huts of home. He was awestruck by the Regent’s enormous motor car, a majestic Ford V8, at a time when few Africans owned vehicles.

The Regent sent Nelson to a succession of mission schools run by British Methodists. He never became a committed Christian, but admits that the strict discipline and mental training permeated his thinking for life. The mission experience wrung the young Mandela between two contradictory aspects of the British colonial presence in South Africa: the brutal military subjugation of the Xhosas, in a series of frontier wars between 1811 and 1877, and the enlightened influence of liberal British education.

The paradox persisted after he won a place at the “South African Native College” at Fort Hare, a tiny university founded by Scottish missionaries which was the only one for blacks in the entire southern African region. When Mandela arrived in 1938 there were only 150 students. At Fort Hare he wore pyjamas and used a toothbrush and toothpaste for the first time, and was fascinated by his first sight of a flush toilet. He admired the principal, Dr Alexander Kerr, an austere Scot and Edinburgh University graduate, who was dedicated to black academic advancement. Dr Kerr exhorted Mandela to obey God and be grateful for the educational opportunities offered by kirk and government. But much as Mandela respected Dr Kerr, his real idol was Victor Sylvester, the world champion of ballroom dancing, which became the young African’s favourite hobby.

Mandela’s Fort Hare progress was halted by his natural streak of obstinacy and rebelliousness. He led a student strike to protest about the poor quality of student food. Dr Kerr warned Mandelasympathetically that he would be expelled if he continued with the protest. Mandela refused to compromise and was thrown out.

Back at the Great Place the Regent ordered Mandela to marry the daughter of the local Tembu priest. Mandela, who had a lifelong eye for pretty women, was horrified: the girl was fat and far from being his dream bride. When the Regent insisted, Mandela packed a single battered suitcase and hitch-hiked 800 miles to Johannesburg, called Egoli, the City of Gold, by Africans.

He arrived in Johannesburg in April 1941, one of thousands of rural blacks who came to Africa’s greatest city each year hoping to find jobs as gold miners, servants or labourers. His first job was as a night watchman in a black miners’ hostel, where he was amused by a notice at the entrance which read, BEWARE: NATIVES CROSSING HERE.

Mandela was befriended by a young estate agent, Walter Sisulu, whose mother was a Xhosa and his father a white judge, Victor Dickinson, who abandoned his black lover and offspring. Sisulu got Mandela a job as an articled clerk with a liberal Jewish lawyer, Lazar Sidelsky, who gave his new recruit a suit. Mandela embarked upon lengthy law studies and met Sisulu’s young cousin, Evelyn Mase, who had arrived from the Transkei to become a trainee nurse. Some 50 years later Evelyn described to a foreign journalist how Nelson had seduced her. Asked what he was like, she sighed: “He was beautiful.”

Nelson and Evelyn married. They moved into a small “matchbox house”, with no electricity or inside lavatory, in Soweto, a township for blacks 15 miles outside Johannesburg. Evelyn in due course bore four children by Nelson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile studying law, Mandela became involved with the ANC, then a staid, disorganised body founded in 1912 to campaign for rights for Africans. With Sisulu and a young Xhosa student, Oliver Tambo, Mandela founded the ANC Youth League with the aim of radicalising the parent organisation. In 1948 Mandela realised just how urgent this had become when the hardline Afrikaner National Party unexpectedly won a whites-only general election victory over Jan Smuts’ less extreme United Party. The Nationalists consolidated existing racial legislation and began extending it under the leading apostle of apartheid, Bantu Affairs Minister Hendrik Verwoerd. Looking back on the National Party’s accession to power, Mandela reflected: “History bequeathed to us two nationalisms (Afrikaner and African) that dominate twentieth-century South Africa. Because both nationalisms laid claim to the same piece of earth - our common home, South Africa - the contest between the two was bound to be brutal.”

In 1952 Mandela opened a legal firm with Tambo, became a snazzy dresser, bought a big Oldsmobile and socialised with great township musicians such as Todd Matshikiza, the composer of the musical King Kong, the singer Miriam Makeba, the trumpeter Hugh Masekela and the close harmony group The Manhattan Brothers. He also began organising resistance campaigns. “Some Indians said he was like Gandhi,” said his close Indian friend Fatima Meer. “I told them, ‘No. Gandhi took off his clothes, Nelson loves clothes’.”

By 1958 Verwoerd had become Prime Minister and embarked upon a truly draconian social engineering programme to implement apartheid. This included mass removals of blacks from areas designated whites-only. Mandela concluded that violent resistance had become necessary.

Meanwhile, Evelyn left him and sued for divorce because of his philandery. Nelson courted and married a beautiful, 22-year-old social worker, Winifred Nomzamo Zanyiwe Madikizela. Winnie, as she was known, was to become Delilah to Nelson’s tragic Sampson, what his friends termed his “major moral blind spot:” But the downward slide in their relationship began only afterMandela had joined the Communist Party, launched Umkhonto we Sizwe, sent clandestine delegations to Moscow and Beijing to secure arms, been arrested and tried, and sent to Robben Island for life. Mandela disappeared from public sight and by the 1970s Western governments and analysts had virtually written off the ANC as an effective force. It was on Robben Island thatMandela faced his greatest test of character as prisoner number 466/64. It was on The Island that he came to believe that reconciliation not revolution was the key to saving both the black majority and the white minority from the horrors of an otherwise inevitable conflagration. Despite all the cruelties of apartheid, he never learned to hate white Dutch-speaking Afrikaners and concluded: “When an Afrikaner changes he changes completely and becomes a true friend.”

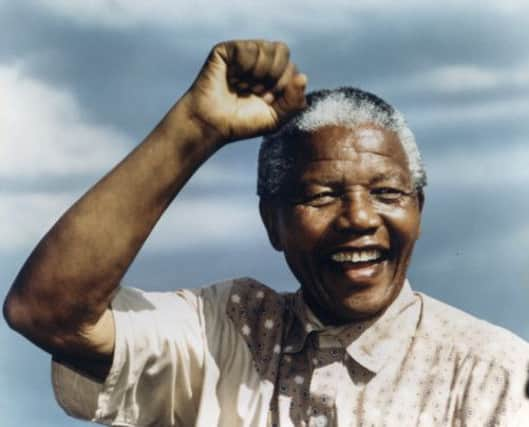

Nelson Mandela finally made a sweet walk to freedom on 11 February 1990, holding hands with Winnie, watched live by hundreds of millions of TV viewers in the biggest human-interest news story the world had known. Mandela’s 27 years in jail had protected him from criticism and earned him credentials few dared question. With the ANC’s 30-year-old ban lifted by a reformist white State President, F.W. de Klerk, Mandela demonstrated his own greatness by resisting any temptation to call upon blacks to rise up violently against their white minority rulers. After three decades in prison, effectively for refusing to abandon his conviction that all people deserve equal rights and justice, Mandela must have known that one carefully honed rabid call by him for revenge could have turned South Africa into the bloodiest of battlegrounds.

As he arrived in Soweto on 13 February1990 after an absence of three decades, the temptation to light the fuse of conflict must have existed. He was heralded by a fleet of low-flying helicopters, looking like gunships out of a Vietnam war movie but actually carrying cameramen from the world’s major TV networks. That he resisted temptation and embarked on a long negotiation to achieve political reform peacefully was the mark of his stature. Who knows what might have happened without Mandela’s moral authority, integrity and commitment to reconciliation?

At the same time, he had to cope with a wayward Winnie who cuckolded him by having an affair with a young lawyer, among several others, and refused to sleep with him after he left prison. This must have been agony for a man who had written to her from prison: “At my age, I would have expected all the urges of youth to have faded away. The mere sight of you [through glass during prison visits], even the thought about you, kindles a thousand fires inside me.”

Despite his private humiliation, Nelson stood by Winnie loyally, but probably unwisely, when she and members of her notorious vigilante group, the Mandela United Football Club, were tried for the torture and kidnap of 14-year-old Stompie Moeketsi, found stabbed to death on wasteland near her Soweto home. Allegations were made in 1997 at South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation hearings that Winnie herself had stabbed Stompie to death next to the open-air jacuzzi behind her Soweto house.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe disaster of his love match with Winnie gave his entire story the dimensions of an epic novel. When he finally divorced her in 1996, Mandela told the judge: “I was the loneliest man during the period I stayed with her. If the entire universe persuaded me to reconcile I would not. I am determined to get rid of this marriage.”

Nelson Mandela was elected the first black President of South Africa in April 1994 and the ANC became the government with 63 percent of the vote in the country’s first all-race election. He retired as State President in 1999, but campaigned on behalf of his designated successor, Thabo Mbeki, even though he had expressed a preference for Cyril Ramaphosa. During the campaignMandela denounced his most effective opponent, Democratic Party leader Tony Leon, a white, as a “Mickey Mouse” politician. But when, shortly after Mbeki’s election, Leon underwent a triple bypass heart operation Mandela demonstrated his fundamental humanity, sense of mischief and self-deprecating humour. Leon, lying in his hospital bed, heard a voice beyond the bed curtain saying: “Hallo Mickey Mouse, this is Goofy.” Through the curtain stepped Leon’s visitor, Mandela.

In 1993 Mandela had been jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize with F.W. de Klerk, for their work in ending apartheid. De Klerk became deputy president in a government of national unity under Mandela, a post he kept until 1996.

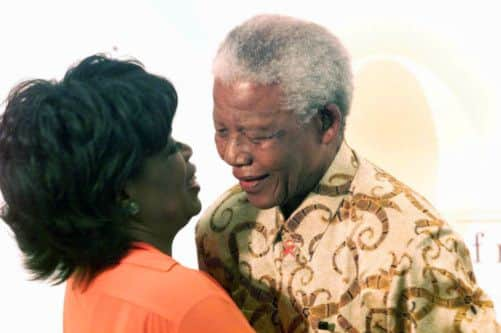

Shortly after retiring from the Presidency, Mandela married Graça Machel, widow of the former President of Mozambique, Samora Machel. In retirement Mandela divided his time between Graça’s white marble-lined house overlooking the Indian Ocean in Maputu, the Mozambique capital, his own home in the former whites-only suburb of Houghton in northern Johannesburg, and a modern house he had built for himself in the Transkei village of his boyhood.

Although Mandela showed all signs of deep contentment in his marriage to Graça, the story surfaced late in the life of this passionate man of how he could have taken a close friend of Indian-origin as his third wife. He had a deep and affectionate relationship with Amina Cachalia, widow of the veteran ANC activist Yusuf Cachalia. After Yusuf died in 1995 and before the marriage to Graça, Nelson declared his ardent love for Amina and asked her to be his wife. In her autobiography, When Hope and History Rhyme, published in February 2013, the month she died aged 83, Amina wrote: “I was not ‘in love’ with Nelson. I loved him dearly and yet I could not bring myself to want him as I did Yusuf, even in our old age.” Mrs Cachalia said Mandela was deeply upset by her rejection of his marriage proposal.

Towards the end, as he declined physically and mentally, his hair turned white, leaning heavily on a stick and unable to remember that close friends had died, Mandela began spending all his time at his Transkei home and from 2010 onwards he ceased making public appearances. From 2011 onwards he lived at his house in Houghton, a millionaires’ suburb in northern Johannesburg, where his health could be monitored daily. Before he died, he was in and out of hospital regularly when his breathing difficulties escalated into pneumonia.

It was part of Mandela’s charm, allied with guts, that he could be humble without a hint of false modesty, someone who insisted he was just an ordinary man who became a leader because of extraordinary circumstances. The fingerprints of this “ordinary” man were firmly impressed upon the final decade of the twentieth century. His was an epic story of great passion and perseverance over many decades. He is survived by Graça, by his former wife Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, and by three daughters – Makaziwe, by his first wife Evelyn, and Zeni and Zindzi by his second wife, Winnie. Three children, two sons and a daughter, predeceased him. He is also survived by 17 grandchildren,12 great-grandchildren and four step-children through his marriage to Graça Machel.