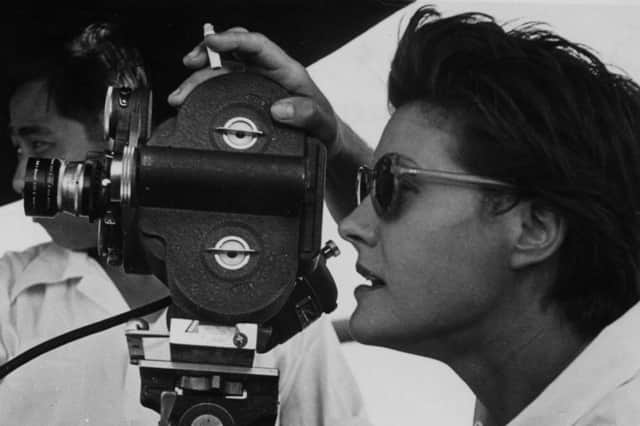

Obituary: Kay Mander, documentary film-maker

In recent times Kay Mander lived in quiet, anonymous retirement in a council house and latterly a nursing home in the Kirkcudbrightshire town of Castle Douglas. And few knew that the frail, grey-haired, old woman with the walking stick had been one of Britain’s pioneering women film directors and the one-time lover of Hollywood superstar Kirk Douglas.

Mander started off in the film industry as a translator, publicist and production assistant in the 1930s, but she got the chance to direct documentaries during the Second World War when so many experienced male colleagues were in the armed forces.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHer directorial debut was a seven-minute short instructing apprentices on how to file metal, but she was always looking for new ways in which to bring worthy, but potentially dry, subjects to life. And when she made a film about malaria she used “microphotography” to film a mosquito biting her and filling up with her blood in close-up.

Commissioned to make a film about a pilot health scheme in the Highlands and Islands, she decided against a straightforward documentary approach, recording doctors and nurses going about their work, and instead wrote her own storyline about a medical emergency and recruited actors to play it out.

Highland Doctor helped pioneer the whole idea of drama-documentary. It was shot on location on Lewis, Harris, North Uist and in the West Highlands and it came out in 1943 as momentum was gathering behind the idea of a National Health Service.

The prevailing wisdom of the times was that documentary-makers should remain dispassionate and keep their distance from their subjects. But Mander was a deeply committed and outspoken member of the Communist Party and she made no attempt to hide it in her work.

In the 1945 film Homes for the People, she had ordinary, working-class women speak bluntly about housing as they went about their daily chores – kitchen-sink drama in the most literal sense. One woman complains that her kitchen must have been designed by a man because it was so badly planned.

However, it is only fairly recently that film critics and historians have acknowledged Mander’s importance, both as a pioneering woman director and simply as an innovative documentary maker. She was the subject of a documentary, One Continuous Take, in 2001 and a boxed set of her films was released in 2010. Russell Cowe, who runs Panamint Cinema, a company that specialises in old documentaries, said at the time: “She developed new techniques in film-making and she led the way on social issues.”

Mander found it tough getting commissions after the Second World War when experienced male directors returned to the industry. She took work as a “continuity girl”, the person charged with making sure, for instance, that cigarettes get shorter rather than longer over the course of a scene.

She was “continuity girl” on dozens of films from the 1950s to the 1980s and worked into her seventies. Films on which she was continuity girl include From Russia with Love, which continued her association with Scotland, a country she grew to love, and the Second World War adventure The Heroes of Telemark, during which she got to know Kirk Douglas.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI interviewed her many years later, at her home in Castle Douglas. She was approaching 90 at the time. Her eyes moistened as she recalled the relationship. “Kirk Douglas was my passion,” she said.

“He had this awful reputation,” she told me. “He flew his ladies in first-class, kept them there for a long weekend, and sent them back tourist.” But she thought he was “wonderful” and she took the initiative in their relationship. “I made approaches to Kirk that I wouldn’t have done to another actor,” she said. Both were married and in their late forties at the time.

Her only regret about the affair was the hurt it caused her husband, the film-maker Rod Neilson Baxter, whom she married in 1940. “I never wanted to get involved with anybody except my husband,” she said. They remained married until his death in 1978.

An only child, she was born Kathleen Mander in Hull, Yorkshire, in 1915. She grew up partly in France and Germany. Her father worked for a company that made radiators. She had hoped to go to Oxford University, but her father lost his job and she was forced to look for work.

While living in Berlin, which was about to host an international film festival, she offered her services as a translator and receptionist and made important contacts. Back in England she worked as a translator on Conquest of the Air (1936), which had a German cameraman and starred a young Laurence Olivier.

In those days women were largely restricted to a few posts such as publicity, continuity, wardrobe and make-up, and Mander ended up with a job as a publicist with Alexander Korda’s London Films.

But the upheaval of the Second World War provided her with the opportunity to direct. After the war she and her husband lived and worked in Asia for a while. She subsequently wrote and directed one feature, The Kid from Canada (1957), a film about a young Canadian boy in Scotland that was made for the Children’s Film Foundation.

Mander had no great ambition to go on making films for children. Despite her left-wing politics and track record as a serious documentary film-maker, she seemed to enjoy working on big-budget Hollywood movies – even with the relatively menial task of continuity – and the chance to meet such glamorous stars such as Douglas, Sean Connery, Julie Christie and Sophia Loren.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the 1970s she did continuity on the film of the Who rock opera Tommy and the television series The Professionals. She moved to Scotland shortly after her husband’s death in 1978 with the intention of making a film about barnacle geese.

She never made the film, but stayed on, living in a chalet on a farm outside Dumfries, and then latterly a bungalow and nursing home in Castle Douglas.

One of her last jobs was as script supervisor on Timothy Neat’s 1989 film Play Me Something, which took her back to the Hebrides.

She never had children.