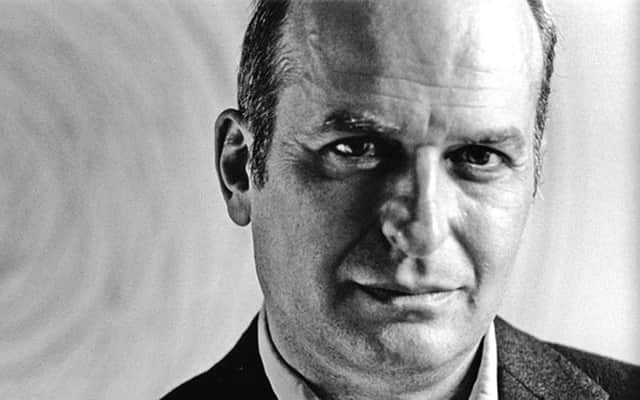

Obituary: Jonathan Woolf, architect and professor

Jonathan Woolf was one of the UK’s outstanding modernist architects of his generation, who designed austerely elegant private homes and who also had an innate ability to impart his passion, enthusiasm and sharp critical intellect to the students he taught throughout Europe and the UK, including the Scott Sutherland School of Architecture at the Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen and the University of Bath.

In parallel with practice, Woolf was a prolific educator, teaching at two of Europe’s most prestigious schools, the Architectural Association in London and the Accademia di Architettura in Mendrisio, Switzerland, before his appointment as Professor of Architecture at Aberdeen, where for a number of years he brought together practitioners from across Europe, helping to inspire a new generation.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWoolf first came to the attention of the architectural and larger world in 2003 with the completion of his RIBA award-winning building Brick Leaf House in Hampstead, which became the first private house to reach the mid-list of the UK Stirling Prize. Fellow architect Jonathan Sergison noted that it made a difference to what the world understands as “London architecture”.

Chosen from a RIBA shortlist in 1998, Woolf was commissioned by two Kenyan-born brothers who wanted a modern white building in the style of Luis Barragan, though Woolf convinced them to have brick, because it was “a material that would age gracefully in the way that the mature elements of the plot – the trees – had done without the need for maintenance”. Also, brick was the palette of the area, Hampstead Garden Suburb.

Influenced by the German-American architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe who designed villas in 1930s Germany, Woolf wanted to use the topography of the plot to create an urban feel, “where a brick building abuts hard up against a stone road, very much like the hill towns of Italy and Spain”.

Described as “an understated building”, Brick Leaf House, situated on the edge of London’s Hampstead Heath, did not fit easily into any ideological category, but it announced its purpose with simplicity and clarity. This extended to the brickwork which, treated consistently throughout, played a key role in this new take on the grand house tradition of north London.

With its hand-made mauve-colour brickwork and mortar, Brick Leaf House sits at the top of a steep, granite-cobbled drive from street level and has two self-contained but interconnected homes, linked by a shared inspirational, cave-like underground swimming pool. The house and its elevations are similar in scale to the trees, a mature English oak and a giant copper beach, and are set between them as a linking element defining the lower and upper garden and maintaining an intimate relationship to the landscape.

Although Woolf did not leave a large body of work, it is perceived to be “one of real originality which will assert a considerable influence in the years to come”.

Born in Golders Green, north London, in 1961, Jonathan Woolf was brought up a short distance away in Hampstead Garden Suburb. The son of an electronics engineer and a social worker, he was educated at Christ’s College, Finchley, before studying architecture at Kingston Polytechnic (now University, from which he received an honorary doctorate in July this year). He demonstrated talent as a student with the university establishing a portfolio prize to recognise his degree project, a housing competition in Venice.

Upon graduation, Woolf worked in Rome and then in London with Munkenbeck and Marshall, where he was given the opportunity to be project architect for the house of art collector Charles Saatchi, which paved the way to the series of exemplary private houses, which came to define his career.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter winning two international competitions, one for an urban regeneration project in Dublin and another for a new office furniture system, which demonstrated an early mastery across a breadth of scale and the role of the house in the city, Woolf founded his own London practice, Jonathan Woolf Architects, in 1990.

He was fortunate enough to have contemporaries such as David Adjaye, Stephen Bates, Adam Caruso and Tony Fretton and Jonathan Sergison, who shared his desire to break with the architectural convention of the time – post-modern classicism and high-tech.

Woolf’s remarkable ability to synthesise ideas of the room, the city and the landscape, history and modernity or the monumental and the ordinary into a singular, refined and comprehensible work of architecture was expressed clearly in his 2007 shortlisted competition entry for the extension to the Stockholm Library, which was viewed by many as by far the most eloquent response to Gunnar Asplund’s 1928 masterpiece.

Also in 2007, Woolf designed Monkey Puzzle Pavilion, erected in the Castlegate as the central hub for Aberdeen’s Six Cities Design Festival, Scotland’s first nationwide celebration of design. It became a great talking point.

Originally inspired by a fragment of a famous building in the Swiss mountains of Graubünden, the Pavilion, which had no floor and rested on the existing granite stones of the square, was made entirely out of sustainable wood and was an unusual shape, taking the form of a cross which was partly in reference to the old Mercat Cross at the Castlegate. Each arm of the cross was a different size of space with either a window or doorway at the end of each of the arms. An exciting glass topped opening in the centre of the space framed views of the sky.

Woolf’s 2010 project, Painted House, comprehensively transformed two 1920s north London semi-detached houses into one extraordinary family dwelling for two brothers and their parents. He had been interested for some time in the way that UK construction methods rely on materials that are becoming thinner and thinner while at the same time striving to retain their surface material qualities.

With an exterior described as “on the severe side”, due its cladding of faux brick tiles, the interior was a revelation with an expansive array of simple, generous, white-walled, light-filled rooms.

The fact that the Painted House struggled with planning permission suggests that conformity had the upper hand, but the virtues of the completed house are its openness to change and the freedom it offers to inhabit it in many different ways.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRenowned Swiss architect Valerio Olgiati pronounced Brick Leaf House and Painted House as “two very beautiful buildings” that are “rooted in the urban traditions of elegant and calm English architecture.”

Woolf’s last built project was the Lost Villa (2014), commissioned by the younger of the brothers for whom he had designed Brick Leaf House. His client secured a plot on the edge of the Karura Forest in Nairobi, where he wanted a house for his family and parents.

The Lost Villa was an exploration of topography and materiality; the walls are of rough-chiselled sandstone rising towards an over-sailing concrete roof that follows the slope of the ground, an arrangement Woolf described dryly as “a ruin under a flyover”.

Woolf’s practice worked on projects both throughout Europe and Africa and went on to complete more than 35 projects, including apartments, houses, studios, offices and hotels.

Ellis Woodman, director of the Architecture Foundation, believed Woolf’s work was “distinguished by a combination of qualities that is exceptionally rare in contemporary architecture. On the one hand it is the product of a profound engagement with history; on the other it remains strikingly free of eclecticism. Above all, its concern lies with the enrichment of space whether through a poetic response to the topography of a site or the artful distribution of a sequence of rooms.”

Woolf died of cancer and is survived by his wife, Siobhan, and their two daughters.