Alf Young: Apple takes a bite out of SNP plans

An engaged community talking about what kind of Scotland its people want to see emerge from our current constitutional preoccupations. We were still on the A81, avoiding a road closure, to reach Callander, when we began to notice a string of vintage sports cars, open-topped even in the weak, rain-threatening sun, heading in the opposite direction. I’m no expert on four-wheel marques, but I ventured to Carol: “I think they’re all Austin Healeys.”

Perhaps it was that old joke from my childhood. “What’s green and comes out of the ground at 100 miles an hour?” Answer: “An Austin Healey Sprout.” But later we discovered the rally was based a few miles away at Crieff Hydro. And, checking online, I found they were indeed Austin Healeys, some even Sprites. Crieff was the base for the week-long, fourth European Healey meeting, which ends today. Clubs from Switzerland, the Netherlands and Sweden, as well as the UK, have been involved in organising the meeting’s mix of road drives through scenic Scotland, a Rest and be Thankful hill climb, even a track session at Knockhill.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe event brought 500 people to Crieff, a group of enthusiasts united by their love of a stable of cars last produced in 1971. These days, they appear to change hands for as much as £70,000. It’s the kind of bond that binds many of us who use the digital devices on which I searched for details of that Healey meeting and on which I am currently writing this column.

Yes, for many, many years, I have been a devoted Apple user.

You won’t find me queuing outside an Apple store at midnight, anticipating its latest product launch. I don’t possess an iPad, although my wife does. My iPhone is an ancient 3GS. But, like any Austin Healey enthusiast, I am sold on Apple’s approach to engineering and design, wired to its operating system and its cloud.

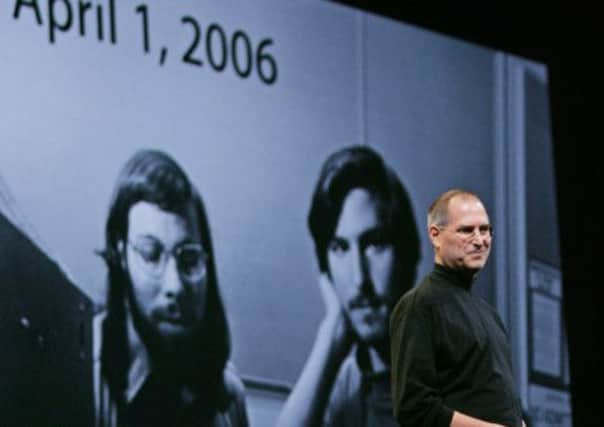

I love all the stories of how Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak started, in the mid-Seventies, to collaborate on building Apple’s earliest devices through the Homebrew Computer Club. How the infant Apple exploited the full potential of the graphical interface they first saw demonstrated at the Xerox Corporation’s Palo Alto research centre. “They were copier heads who had no clue about what a computer could do,” Jobs said later, of a Xerox management that couldn’t see the sheer scale of the breakthrough their researchers were sitting on. “They just grabbed defeat from the greatest victory in the computer industry.” Apple capitalised mightily on the work of others.

However, this devoted Apple user is appalled by what has emerged in recent weeks about the convoluted lengths that the company has gone to to pay as little tax as possible on its profits, earned on selling Apple products and services outwith the Americas. A top rate of just 2 per cent on sales of $74 billion (£49bn) over the past three years, according to recent senate hearings in Washington. Even Apple’s surviving co-founder, Wozniak, has condemned the revelation. He created the Apple computer, he says now, “to empower the little guy”.

But the tax system is set up to benefit large transnational corporations, not the little guy.

Wozniak was speaking at a business conference in Derry. At the other end of the island of Ireland, in Cork, lies the site of all this tax alchemy. Apple opened its European headquarters there in the early 1980s. Once upon a time, it assembled a range of Apple components and products in Ireland. But these days are long gone.

Wooed originally by a decade or more in which it was exempted from any tax on its Irish profits, Apple nowadays employs some 4,000 people there on multilingual customer support and other service functions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Cork complex is also, according to the US senate investigation, the hub for Apple Operations International (AOI), a key holding company that processes the proceeds of sales of Apple products and services throughout many markets in Europe, the Middle East and Africa and perhaps even further afield. It is controlled, according to a Guardian investigation this week, by a 49-year-old Irish accountant, Cathy Kearney. She is the only European director of AOI, but has attended only one of its board meetings in California in person. Most of the time she’s on the end of a phone.

AOI, which accounted for sales of $22bn in 2011 – two-thirds of Apple’s entire profits – is an unlimited company, accountable for tax on those profits in no known tax jurisdiction on the planet. So, it doesn’t pay any – certainly not to the government of the Irish Republic. As the US senate inquiry made clear, in this case “i” stands not for a pod or a pad or a phone, but for a corporate entity that is imaginary or invisible.

Politicians in Dublin are distressed at being branded in Washington a tax haven. From the Taoiseach Enda Kenny down, they have been firing off diplomatic ripostes across the Atlantic, disputing any such charge. But while the Irish tax authorities may indeed charge that state’s 12.5 per cent corporation tax rate on Apple profits generated within the Irish market, the vast bulk of the Apple profits funnelled through Cork appear not to be taxed by any jurisdiction.

They contribute hugely to a $145bn Apple cash pile invested who knows where that the company refuses to repatriate to the United States, where it would currently incur a tax charge of 35 per cent. But this is where the Irish approach to undercutting everyone else on corporate taxation has ended up. As Fintan O’Toole put it in the Irish Times this week: “We have put all our eggs in one flimsy basket; the idea that our place in the world is as a conduit for corporate tax avoidance.”

Irish GDP, O’Toole continues, is now “largely a fictional construct”. Now even GNP, the more credible measure of national economic virility, is polluted “by vast ‘profits’ of brass-plate companies” nailed to doorways in Dublin, but contributing next to nothing to the Irish economy. In the name of tax equity, there is a crying need for nation states around the western world to get their act together and find ways of curbing the most venal aspects of transnational corporate tax avoidance.

But here in Scotland, an aspirant nation state, all we hear is a desire to get in on the corporate tax cutting act. The SNP leadership says it wants an independent Scotland to undercut the prevailing rest of the UK rate on corporate profits by three percentage points. Assuming Chancellor George Osborne delivers on his promise of a main UK rate of 20 per cent, that means an independent Scotland rate of 17 per cent.

That won’t impress the like of Apple’s Cathy Kearney in Cork. One wonders whether the “modelling” Alex Salmond claims his officials have done on their proposed cuts impact on jobs and growth included the possibility of unlimited, tax-jurisdiction-free corporate entities setting up in Scotland and paying no tax to anyone. Or has the First Minister’s promise of a tougher collection regime already figured out how, single-handedly, it will combat that growing menace?