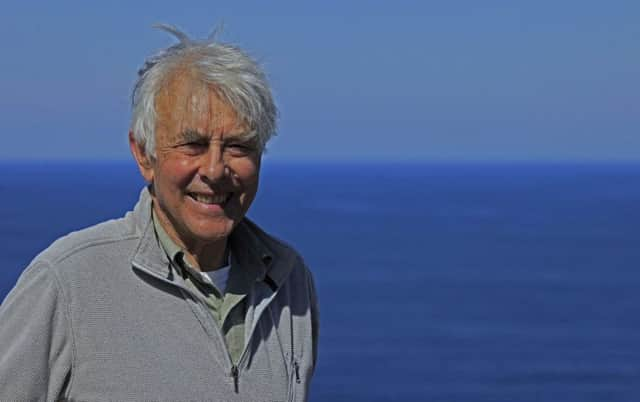

Obituary: John Busby, artist, teacher, writer and naturalist

One cannot draw or paint ‘what one sees’ in front of one without being aware of what is happening on the page or canvas in the process. However fascinating the subject matter, we need equal fascination with the whole business of making marks with which, in a childlike way, we can identify. To copy nature without resolving our own thoughts is a barren process.” John Busby, from Drawing Birds, 2004.

While at school in the mid-1980s, I managed to purchase a book that was to change my life. It was the first edition of Drawing Birds, an RSPB Guide, by John Busby, and it led me into a whole new way of seeing and expression as a visual artist.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn was a pioneer of working direct from life and he had that exceptionally rare talent of making the most difficult seem easy. His drawings flowed with life and character, his birds and animals deftly flew and skipped across the page with a movement seldom achieved before. His landscapes and rock pools invited you in to explore and discover, with beautiful balances and harmonies of colour – reflections on the natural world. Only the best of artists can lure you in to see and feel this way.

In 1988 he started an annual, week-long seabird drawing course, based on the East Lothian coast, which still continues to this day. It was on this course that I first met John personally. I remember it as if it was yesterday, driving eight hours direct from college in Wales, and introducing myself to John on the steps of the Blenheim Hotel in North Berwick.

I was instantly struck by a warmth and an aura from possibly the most generous and encouraging person I have ever met. It was to be a life-changing week in so many ways, and the chemistry between the tutors, John, the late David Measures and Greg Poole, was exciting and inspirational.

Coming from college I was raw, exploding with a will to try and paint what I saw, but until that week unable to channel a direction. It was this nurturing, this supportive encouragement that stayed throughout the 20-plus years I was lucky enough to know John, and have him as a special friend.

Talking about gannets in 2005, John said: “It needs a strong wind for the gannets to hang in the up-draught over the Bass Rock. They balance their weight against the thrust of the wind – wings, neck, feet, all making adjustments to keep the centre of gravity in the right place for the bird to remain almost stationary. It is one of the most challenging actions to draw and achieve equal buoyancy of line – to balance the drawing as delicately as the bird rides the wind.”

I’ve had the pleasure of being on the teaching staff of the course for well over ten years now, and will continue to push the strong ethos and philosophy that John so passionately set in stone. The course has seen hundreds of participants from many parts of the world, all encouraged and shown ways of depicting the most challenging of subjects – whirling seabirds against spectacular towering cliffs. With the aid of the maestro, all this became possible.

John was born in Bradford in 1928, before the family moved to Menston, a village in the heart of Wharfedale, where his passion and love of the outdoors blossomed. He attended Ilkley Grammar School and followed his love and talent for drawing and painting, leading him to study at both Leeds and Edinburgh Colleges of Art, though first he completed two years of national service in the RAF.

At the end of his studies and a postgraduate travelling scholarship, John was offered a teaching post at Edinburgh College of Art, which he enjoyed from 1956 to 1988. He was a natural teacher, with a never-ending patience and generosity; he had a ability to lift the room, in his quiet and unassuming way.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn also chaired the committee that ran the 57 Gallery in George Street, Edinburgh, was president of the Society of Scottish Artists 1973-75, member of the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour, and of the Royal Scottish Academy. He was a founder member of the Society of Wildlife Artists, and a key member of the Artists for Nature Foundation. In 2009 he was declared Master Wildlife Artist by the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum, in Wisconsin, USA. He exhibited widely in both his adopted Scotland and his native England: with solo exhibitions in Edinburgh, Lavenham and Dumfries, as well as a major retrospective at Bradford City Art Gallery in 1999.

How poignant it is that as I write this, we have just learned of the passing one of John’s great friends, the naturalist Bryan Nelson. It was this friendship that extended John’s career into illustrating many books, including Birds in Mallorca (1988).

Of his own books, the first, published in 1982, was The Living Birds of Eric Ennion. This was John’s tribute to an artist he much admired and whose approach, through meeting in Northumberland in the early 1950s, had been a revelation of what was possible in the difficult art of portraying birds.

More books followed – Nature Drawings (1983), the influential Drawing Birds (1986, 2004), Land Marks and Sea Wings (2005) and Looking at Birds – An Antidote to Field Guides (2013). His final book, Lines in Nature, will be published by Langford Press later this year. He was a committed Christian, and classical music was another love. It was while singing in the Edinburgh University Singers that he met a young mezzo-soprano called Joan. They married in 1959, and had three children, Philip, Rachel and Sarah, and nine grandchildren.

Humour and his gentle way is my abiding memory of John. The times we sat beside each other such as on the Bass Rock, when a chuckle would erupt, followed by a hmmmmm – it would be John, having seen immature gannets pulling at each others’ tails while hanging in the wind like puppets on strings, rapidly and magically drawing the action with ease.

I recall too struggling to make sense of a New Forest landscape while on a Society of Wildlife Artists’ Project, while John drew remarkable tree animals – not living animals sitting in trees – but the animals the gnarled ancient branch shapes created, a conger eel, a strange seahorse-type creature. That’s what John did; he saw where others could not.

John was an artist who taught many to see, and with a wit and humour as gentle as his palette of rock pool greys. He was the mentor who would waddle around the room trying to live as the character of a penguin; he was a genius, a presence, an inspiration and a vision with a rare ability to connect that will stay with us forever.

He will be hugely missed – but seldom will there be many artists who will leave such a legacy. We had a beautiful afternoon together recently, when he visited the house and, as enthusiastically as always, thoroughly enjoyed looking at my recent paintings of long-eared owls as well as fieldfares and redwing. His ever-alert artistic eye connected so instantaneously to a set of complimentary colours, and he gently laughed at the curious posture of one of the owls. He relished another’s fortune at seeing something special just as much as he would have done had it had been himself. That was John.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1981, John wrote: “I must say it is enjoyable to have commissions, though important to work on paintings for their own sake in order to make discoveries beyond oneself. Trying to externalise experiences by painting, writing, etc helps to understand them and to be more receptive. Being receptive and willing to change and grow makes one most alive I think – more vulnerable to both pain and joy.”

A very special retrospective exhibition will be held at Nature in Art, Wallsworth Hall, Twigworth, Gloucester from 2 August to 6 September. I would urge you to see if at all possible.