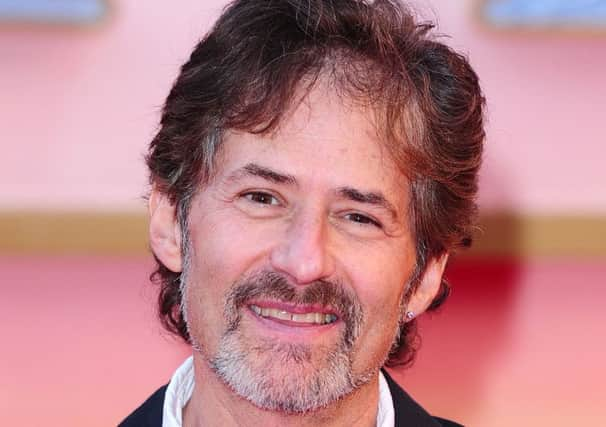

Obituary: James Horner, Oscar-winning composer

James Horner was an American composer and conductor whose work had for three decades been associated with some of the most acclaimed and commercially successful films in history. He was particularly well-known for his collaborations with James Cameron, having worked with the director on the two highest-grossing films in history, 1997’s Titanic and 2009’s Avatar. He co-wrote Celine Dion’s huge international hit My Heart Will Go On for the former, and his career awards included two Oscar wins and a further eight nominations.

Horner was born James Roy Horner in Los Angeles – the city he would call home for practically all of his life – to immigrant parents. His mother was named Joan (née Frankel), while his father was the Slovakian-born (then Bohemian), three-times Oscar-nominated art director and sometime television director Harry Horner, whose final film before retirement was 1980’s The Jazz Singer, starring Neil Diamond.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Horners also had a younger son, the set designer and director of documentary films and commercials Christopher. A keen pianist from the age of five, Horner spent time in London after leaving school, studying at the Royal Academy of Music, before returning to the States to complete his education, first at the University of Southern California and then at the University of California in Los Angeles.

With youthful designs on stepping into the family business and working in film composition, his first self-composed classical work was premiered by the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra and some early work arrived when he scored some short films for the American Film Institute.

While working on these projects throughout the 1970s, Horner taught on the music theory course at his alma mater, UCLA, although his first fully-fledged film work saw him give up this sideline to concentrate fully on composition.

Like many later linchpins of the Hollywood establishment he cut his teeth working for the prolific exploitation director and producer Roger Corman, scoring a procession of his cheap and quickly made movies for a few years around the turn of the 1980s.

Horner’s debut feature film proper for Corman was the 1979 mob flick The Lady in Red (not to be confused with the Gene Wilder romantic comedy The Woman in Red, which came five years later), while his other early work included the 1980 Star Wars cash-in Battle Beyond the Stars, Oliver Stone’s second film The Hand (1981) and the Wes Craven horror flick Deadly Blessing (1981).

These were fallow years in terms of critical recognition, although they brought Horner the most important professional relationship of his life; it was here that he met Corman’s then model-maker James Cameron, who went on to serve as art director on Battle Beyond the Stars.

His first major calling card as a composer came in 1982, with the score for a sci-fi film of an altogether more prestigious stripe in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

Faced with a budget much reduced from the first instalment’s three years previous, director Nicholas Meyer took a chance on the young Horner in place of original composer Jerry Goldsmith, partly on the strength of a strong demo and partly due to financial imperatives. Meyer later joked that he took on Horner because he couldn’t afford Goldsmith, and when he came to film Star Trek VI (1991), he couldn’t afford Horner either.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe intervening years saw the composer’s stock rocket, particularly due to the Academy Award nomination which he earned for his score to Aliens (1986), his first Cameron collaboration.

Mixing the eerie and the fast-paced in perfectly measured amounts for a sci-fi action thriller, the time pressures both were working to in order to finish the film saw Horner bemoan the experience afterwards, saying he wouldn’t work with Cameron again. Before he relented when faced with the tantalising prospect of working on the big-budget and hugely hyped Titanic a decade later, Horner went on to consolidate his status with further Oscar nominations for Field of Dreams in 1989 and both Apollo 13 and Braveheart in 1995 (directed by Ron Howard and Mel Gibson, respectively, two more frequent collaborators).

The breadth of subject matter demonstrated the variety of emotions a Horner score was able to convey, blending orchestral atmospherics with a sense of the pastoral and the personal.

This folk element came into play again on Titanic, for which Horner won both his Academy Awards, with Cameron’s hard stipulations that he wanted no violins and no individual songs forcing Horner to improvise a distinctive period feel.

Hoping that he knew better on the last point, Horner secretly recorded a version of My Heart Will Go On (co-written by Will Jennings) with Celine Dion and presented it to Cameron late in post-production.

The director liked it and the climactic track went on to be the year’s biggest song and one of the most successful hit singles ever.

Further Oscar nominations followed in 2001 for A Beautiful Mind, 2003 for House of Sand and Fog and 2009 for Avatar, his third and final Cameron collaboration, and Horner’s stated most difficult project for its combination of world influences and choral song elements.

At the time of his death, his output stretched to well beyond 100 projects, from the Walt Disney comedy Honey I Shrunk the Kids to the sting for the CBS Evening News.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA keen pilot with his own licence to fly and a collection of small aircraft, Horner died when the two-seater aircraft he was piloting on his own over the Los Padres national forest near Santa Barbara crashed on the morning of 22 June.

Survived by his wife Sarah and their two daughters, Horner’s passing inspired tributes from across Hollywood.