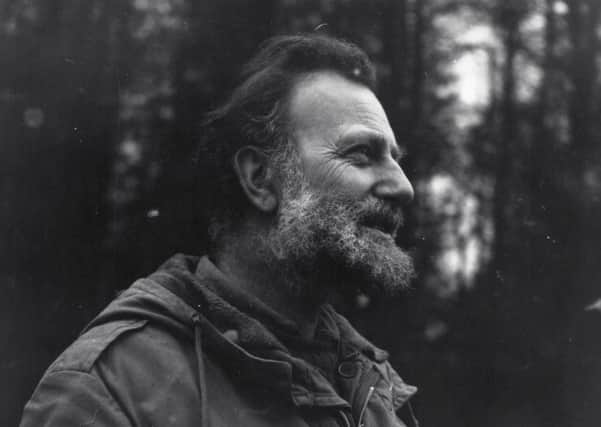

Obituary: James Donaldson Lockie, ecologist

COMBINING a kind and gentle nature yet with firmly held opinions, James Lockie’s life also combined two careers: as a brilliant research ecologist and university lecturer and as a maker of Whim Looms, sold worldwide. His deeply held concerns for the care of the planet were still active in the last months of his long life when he wrote to Scottish ministers about the potentially disastrous consequences of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership aimed at reducing regulatory barriers for big business.

After school at the Edinburgh Royal High, he followed his father into the General Post Office as an engineer and, despite being in a reserved occupation, transferred to the Royal Air Force during the Second World War, training to fly fighters and bombers. He completed the No 1 British Flying Training School course in Terrell, Texas in the spring of 1945, so just missing flying on combat missions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite his earlier engineering training, Lockie enrolled at Edinburgh University to read zoology, followed by Balliol College, Oxford, where he completed a DPhil on the breeding behaviour of jackdaws, rooks and other corvids.

Some of this research took place at Wytham, the woodlands near Oxford, where numerous ecological studies have been carried out and where Lockie first met Aubrey Manning, who later became a colleague at Edinburgh University.

At this time Lockie and his Dutch wife Beatrijs lived in a caravan, the first of many uniquely “Lockyish” habitations that they later created in Scotland.

After Oxford, in 1954, Lockie was amongst the first tranche of scientists employed by the Nature Conservancy, the excellent public agency which successive governments later chewed away because of it being too outspoken.

One of Lockie’s early research projects, while working at its Scottish headquarters in Edinburgh, was on the breeding habits and food of short-eared owls following a vole plague in the Carron Valley, an important type of predator-prey relationship much studied by population ecologists.

Later, Lockie carried out research on the food of pine martens and on golden eagles, the latter with Derek Ratcliffe, contributing to work which lead to the banning of certain pesticides.

In the recently published Nature’s Conscience, about Ratcliffe’s life and legacy, there is a photograph of Lockie and Ratcliffe sitting beside a coiled length of rope on rough grassland somewhere in the north-west Highlands and between them are no fewer than seven golden eagles’ eggs. There was a cast-iron scientific reason for the eggs having been removed but it still caused a fearful row when the photograph was shown at a public lecture.

After promotion to senior zoologist in the Nature Conservancy, Lockie made a sideways career change to become a highly respected and inspiring lecturer in conservation science at Edinburgh University in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith Donald NcVean, Lockie co-authored Ecology and Land Use in Upland Scotland, published by the Edinburgh University Press. In Adam Watson’s review in the Journal of Animal Ecology he wrote that, although small, this book was packed with meat and good value, wherein the two authors combined their wide experience of research and practical problems in land use, land capability and vegetation communities, enriched by controversial aspects of managing animal populations.

Their efforts to examine the highly charged conflicts of upland use from an ecological view remain as needed today as when their book was first published in 1969. Manning writes of Lockie at this period that he was a much-loved lecturer, particularly skilled at teaching in the field where he made simple pieces of apparatus, such as small mammal traps, which always worked.

Despite the convenience of life in Edinburgh’s Hermitage Gardens, in the early 1970s the Lockies bought the Whim at Lamancha, Peeblesshire, a three-sided, 18th-century “square” stable block originally built for the Duke of Argyll, comprising several cottages, bothies and a large leaky-roofed shed.

Here, the Lockies, by now assisted by growing-up children, rebuilt the derelict houses. Encouraged by Beatrijs’s skills at spinning and weaving on a small Inkle loom, Lockie took early retirement from his university post and equipped the huge shed to make full-size eight-shaft Whim looms.

This involved importing a five-ton pillar drill for cutting large mortises and sourcing timber for the heavy frames. Whim looms were sold world-wide, including on the Falkland Islands. On occasions Lockie accompanied a disassembled loom to its destination where he could reassemble the beautifully interlocked frames.

Sallie Tysko of Driftwater Weaves in the Western Isles writes that her Lockie Loom is “just perfect; he was a wonderful loom maker and people will be using his large looms for years to come.”

In the mid-1970s, Lockie assisted the Countryside Commission for Scotland by acting as the external moderator for the commission’s countryside ranger training course, thereby ensuring high standards in teaching and certification.

For several years Beatrijs taught at the Rudolph Steiner School in Edinburgh and encouraging the development of young minds was a feature of Lockie households. Indeed, at the respective ages of 78 and 81, the Lockies visited the Maldives at the invitation of the United Nations to help set up a kindergarten.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTheosophical discussions among friends were a regular feature of life at the Whim. On one such evening there was a scratching at the door, and when it was opened a pig cantered in to take up its usual position by the hearth. The many Lockie stories of their close-knit life are full of such incidents.

From the Whim the Lockies moved to St Abbs, where they lived in a magical house at the harbour, lashed by winter gales, where Beatrijs’s garden was reduced to a few crannies amongst salt-laden rocks and her kindergarten to a cupboard under the stairs.

Meanwhile, Lockie joined forces with other villagers to move a fishing boat to the top of the village where at one time it became the main focus for a museum (now gone) about the fishing fleets of past centuries. In their late 60s the Lockies moved back inland to Crosslee, which comprised five acres of woodland, outbuildings and a charming old farmhouse near the Ettrick Water, south-west of Selkirk.

Here there were more strenuous joint activities in the kitchen garden, woodland and outbuildings, in one of which a barn owl raised a family. Lockie’s 80th birthday was celebrated on 2 May, 2004, when lucky guests were able to drive away with slices of a fallen sycamore tree, fond memories of Crosslee and a half century of judgment-free friendship.

Finally, in 2014 the Lockies moved to Coldingham, into a much smaller and more manageable property with the eminently perfect address of Paradise Lane and typically Lockyish “upside down” construction where one enters from the street on the first floor and descends to the ground floor living room and kitchen.

Recently Beatrijs has re-hung more than 90 pictures and meals begin in the traditional Lockie way: holding hands in a circle of companionship.

James Lockie is survived by Beatrijs; their five children, Neil, Hamish, Gisela, Finlay and Calum, and seven grandchildren.