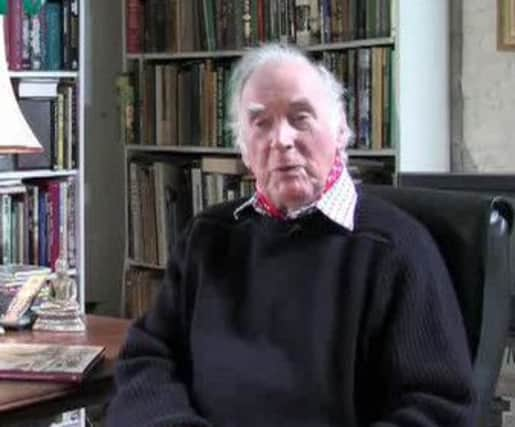

Obituary: Jack Chalker, artist and teacher

Jack Chalker was a British soldier and artist, who risked possible execution on a daily basis in order to secretly chronicle the inhumane conditions and the brutal regime that the Japanese Imperial Army imposed upon Allied prisoners of war working on the notorious Burma-Siam Railway, the so-called Death Railway.

The railway gained notoriety through Pierre Boulle’s book but particularly through David Lean’s film, The Bridge on the River Kwai, although it did not portray the whole story.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChalker’s pictures – sketches, monochrome washes and water colours – were not only haunting and harrowing but left one wondering how one human could brutalise another to such an extent. He lamented: “The sad thing is that here is a race, the Japanese, with an enormous sense of beauty, and yet suddenly there was this.”

Chalker added: “The brutality was so excessive and horrifying – and so unnecessary.”

Chalker, a bombardier with the Royal Field Artillery, was captured a month after his arrival in Singapore, 15 February 1942, and like many had not fired a shot in anger. With the surrender of more than 100,000 British, Indian and Australian troops, this was one of the greatest defeats in the history of the British Army and probably Britain’s worst defeat in World War Two; it clearly illustrated Japan’s fighting tactics – a combination of speed and savagery.

For the Japanese army, which followed the culture of bushido, the so-called Samurai code of frugality, loyalty to the Emperor and honour unto death, the capture of prisoners in battle reduced the status of the captured to one of almost worthlessness.

Chalker was held briefly in Changi prison and two labour camps before being sent to work on the Burma-Siam Railway, arriving at a camp on the Konyu River in Thailand after a five-day train journey crushed into metal boxcars, in stifling heat and with little food or water. Hiding his brushes and paints in his pack, he had already started to secretly sketch acts of brutality that would become the norm.

Already surveyed by the British government of Burma at the beginning of the 20th century, the proposed route, through hilly jungle terrain divided by numerous rivers, was deemed too difficult to complete.

However, the Japanese were forced to start the 258-mile long line between Bangkok and Rangoon, in June 1942, because their sea supply routes were vulnerable to Allied submarine attacks. The labour force comprised 180,000 conscripted Asian labourers and 60,000 Allied PoWs. In the year it took to complete the railway, half the Asian workers and 12,399 Allied prisoners died, more than 6,300 of them British.

Upon arriving, Chalker had a 200-mile march to Three Pagodas Pass, Kanchanaburi Province, western Thailand, where work began. Working up to 16 hours a day and surviving on just 250gms of rice per day, life was a relentless battle of survival, fighting, malnutrition, dysentery, diarrhoea, jungle sores, malaria, beriberi and dengue fever, a mosquito-borne tropical disease. Along with this were ritual and habitual beatings, humiliations, torture and executions carried out by the Japanese guards.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChalker and fellow PoW artists Philip Meninsky, Ashley George Old and Ronald Searle created a unique record of prisoners suffering and the brutality of the Japanese regime. Tough and physically strong men became skeletal, barely able to walk but the guards beat them and devised humiliating and exhausting punishments, such as being tied to poles with buckets of stones or water hung round their necks or holding heavy rocks above their heads for hours. The artists captured it all.

Chalker was once caught “hiding some stuff”, however, and his drawings were destroyed. “This was only a prelude to the real beating, and the next two days were a nightmare,” he recalled. Unperturbed, he continued and devised more ingenious ways of hiding his work, in false limbs worn by amputees, and bamboo reeds and poles buried or secreted in hut roofs.

Chalker used to steal equipment. However, the camp commandant unwittingly helped by giving him some brushes and paint, after telling him to produce “20 watercolour postcards a day” to send to his family in Japan “under threat of being beaten-up and incarcerated unless they were forthcoming”.

After the war in 1945, Chalker joined the Australian Army HQ in Bangkok as a war artist; some of his work was used in evidence at the trials of Japanese officers and NCOs at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

Chalker did not talk about his war-time ordeal or look at his pictures for almost 40 years. In 2002, ill-health forced over 100 pieces to go under the hammer at Bonhams, London. “I feel reluctant and in a way guilty about doing this, but it will help us out,” he said.

They sold for almost £200,000, being acquired by several private collectors and museums, among them Britain’s National Army Museum. The highest-selling lot, an oil painting and a pencil drawing of Australian surgeon Colonel Edward “Weary” Dunlop performing an amputation, sold for £24,600.

Chalker said: “I am rather stunned at the success of the sale, but I am very moved indeed by the kindness I have received.” Born in London in 1918, Jack Bridger Chalker was the son of a station master, who was appointed MBE for the transportation of British troops during the Great War (1914-18). Jack successfully won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art but his studies were interrupted by the outbreak of World War Two, whereupon he joined up.

While building the railway, Chalker contracted dysentery and dengue fever after six months, and spent the next two-and-a-half years in Japanese-run hospital camps. He went to Chungkai hospital camp, established in an attempt to care for thousands of sick and dying men. In early 1944 the army surgeon Dunlop arrived; recognising Chalker’s drawing talent, he asked him to start making secret records of the prisoners’ medical conditions.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDrawing from his sickbed in the dysentery hut, Chalker drew stick-like figures with protruding ribs lying on the floor in a squalid, unfurnished room. Others showed similarly emaciated, frail figures, while he also studied tropical ulcers and items of medical equipment fashioned from army-issue water bottles and old motor tyres.

By the end of 1944 Dunlop’s medical team had moved to the hospital camp at Nakom Paton, and Chalker went with them. He continued his secret medical drawings, and recorded the people, events and landscape.

On his return to England, Chalker resumed his studies, graduating from the Royal College of Art in 1951. He then taught art history and was director at Cheltenham Ladies’ College before becoming the principal of Falmouth College of Art and, in 1957, principal of West of England College of Art, where he remained until his retirement in 1985. Afterwards, he worked as a medical illustrator and was elected a fellow of the Medical Artists Association of Great Britain. He also gave regular talks about his war-time experiences.

More recently, Chalker and his illustrations were used in a BBC4 documentary, screened earlier this year, Building Burma’s Death Railway, dealing with the reconciliation of former prisoners with their Japanese captors.

He wrote two books: Burma Railway Artist (1994) and Burma Railway: Images of War (2007), the latter published in Japan too.

Chalker married three times. First to Anne Maude Nixon in 1939, with whom he had a son. They were divorced in 1957. During the 1950s, he married Jill with whom he had two children. Following Jill’s death his final marriage was to Helene Merrett-Stock in 1965, who survives him, as do his children.