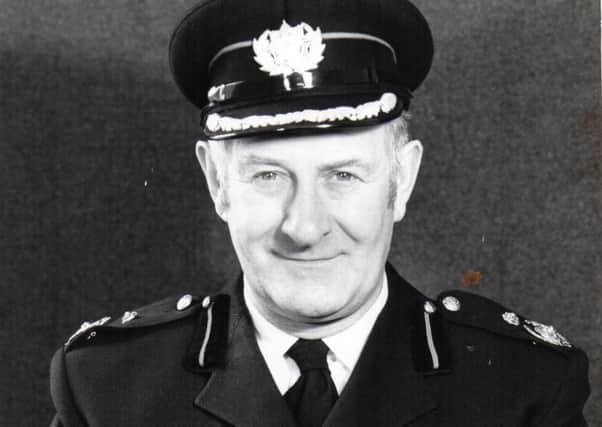

Obituary: Ian McMurtrie MBE, firefighter and museum curator

WITH a family heritage of firefighting stretching back generations, it could reasonably have been expected that Ian McMurtrie would keep up the proud tradition and join the service without a second’s hesitation.

But when the youngster found himself forced to leave school at just 13, as a result of war being declared against Germany in 1939, he ended up working in the printing trade.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe followed that with spells as a plater in the Leith shipyards, soldiering with the army in Palestine and manufacturing steam locomotives in England, before he finally returned to Edinburgh and joined the ranks of the service that had been the core of working life for his great grandfather, his grandfather and two uncles.

It had ultimately been a long and circuitous route, involving a certain degree of heartache – he missed his beloved Stockbridge and the woman who was to be his wife – but he would go on to rise to the rank of acting deputy firemaster, see both of his sons follow in his footsteps and be instrumental in highlighting Edinburgh’s place as the first city in the UK to have a municipal fire brigade, earning a reputation among fellow firefighters as an officer and a gentleman.

Born in the capital’s Stockbridge, he was very close to his grandfather, station officer Tom McMurtrie, and particularly proud of the fact that his great-grandfather, Sergeant Thomas McMurtrie, from the Stockbridge station, had been involved at the site of a heroic rescue in 1861, following the collapse of a seven-storey tenement in the Old Town.

The 16th-century building had come crashing down in the early hours when most of its 77 residents were asleep. A total of 35, including entire families, were killed in the disaster but by dawn that day, as hope of finding any more survivors was beginning to fade, the legs of a young boy were spotted sticking out of the debris.

The youngster, Joseph McIvor, aged 12, is said to have shouted out: “Heave awa lads, I’m no’ deid yet,” and was successfully pulled from the rubble.

Following the rescue he was immortalised in sculpture with a stone carving of his face adorning the entrance to the rebuilt building at Paisley Close, the banner above bearing the more genteel version of his cry “Heave away chaps, I’m no’ dead yet.”

Sergeant McMurtrie’s great grandson would also have his fair share of drama in the service but not until he had spent the first decade of his working life in a diverse variety of roles. Barely into his teens, he began as a print runner, ferrying stories to typesetters.

Then at 17 he started an apprenticeship as a ship’s plater with Henry Robb shipbuilder at Leith Docks, where merchant ships, destroyers and minesweeper were repaired during the war. Working in a reserved occupation and therefore vital to the war effort meant he could not do his bit for King and country on active service but in 1942 he joined the Home Guard, serving as a rifleman based at Edinburgh Academy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDetermined to join the army, he eventually managed to get permission to leave his apprenticeship and sign up as a regular soldier, albeit after the war.

Released from the industry, he joined the Royal Scots and was later transferred to the Ulster Rifles, serving in Palestine, where he saw Christmas in the Garden of Gesthemane, an event that had a profound effect on him.

After leaving the army he returned to complete his apprenticeship but with the shipbuilding industry in decline post-war he was subsequently made redundant. In 1949, with work proving hard to come by, he moved further away from his home and heritage, venturing south to take up employment in Manchester, building railway engines.

By this time he had already met Betty, his bride-to-be, and missed both her and Stockbridge – the capital of Edinburgh, as he called it. Unable to settle in Manchester, he returned home and opted to join the fire service.

He started with the South Eastern Fire Brigade at Dalkeith Fire Station in December 1949, completing his basic training in Paisley before being posted back to Dalkeith. From there he went to Lauriston Fire Station where he spent eight years.

Moving up the ranks he was sent to London Road Fire Station as a leading fireman and three months later was promoted to sub officer, serving in that capacity at both Musselburgh and London Road before being promoted to station officer at Dalkeith.

However, he was soon on the move back to Lauriston, in charge of White Watch. In 1966 he was promoted to assistant divisional officer in B Division, based at force headquarters in Lauriston, with responsibilities including press relations and the fire brigade museum. He went on to reach the rank of assistant firemaster and served, for a short time, as acting deputy firemaster prior to retiring in 1983.

A modest man who rarely discussed the incidents he attended, he once dived into Leith Docks to rescue passengers from a submerged car that had left the road. And, during a time when the fire service trained merchant seaman to firefight at sea, he sailed on an oil tanker to determine its training requirements only to be effectively “missing at sea” for some considerable time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen his wife eventually heard from him it transpired they had been trapped by ice in the Baltic and had had to wait for an ice breaker to free the vessel.

He also had a taste of fame when he appeared on television as a uniformed firefighter in an episode of Dr Finlay’s Casebook – the doctor’s house had gone up in flames and the GP’s housekeeper and receptionist Janet had to be rescued on the back of a fire engine.

But his greatest professional legacy is undoubtedly the Museum of Fire which, in its various guises, he had been involved with for more than half a century, being appointed curator in 1963. As the unsung driving force behind the museum, he was instrumental in saving many artefacts over the years, begging and borrowing display cases in which to show the exhibits.

On retiring he returned to the service as civilian museum curator and in 1984 his work was recognised with the MBE. The facility, in Lauriston Place, where he spent most of his working life, documents the history of the UK’s oldest municipal fire brigade, established in 1824, and contains firefighting equipment dating back to the 1400s.

Although he retired again from the fire service at the age of 65, he continued the connection with the museum when he was appointed honorary curator and could be found two days a week either in the museum at his desk or in the library.

A fount of all knowledge concerning the fire brigade in south-east Scotland and its history, he answered queries from people from all over the world. And, if he did not already know the answer, he knew where to find it in the vast collection of reference materials, much of which he was responsible for retaining.

“He was an officer and a gentleman held in the highest esteem by those who met and knew him, including generations of firefighters,” said Alex Clark, deputy chief fire officer, Scottish Fire and Rescue Service.

“His historical knowledge of the fire and rescue service and joy and generosity in sharing his memories of a bygone area, along with his commitment to preserving the Museum of Fire, cannot be replicated.”

Mr McMurtrie is survived by his wife Betty, whom he married in 1953, their children Kenneth, Jamie and Kirsty, six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.