Obituary: Edward Gillespie Nairn, bookseller

The Aberdeen University Press Concise Scots Dictionary defines “Keelie” as “a rough male city-dweller, a tough, now esp from the Glasgow area, orig with an implication of criminal tendencies”, so it is inconceivable that anyone could agree with Nairn’s description of himself as “just a Glesca keelie” – and ironic that in the plural the “Glesca Keelies” is the nickname for the Highland Light Infantry – but typical of his quiet, but acute, sense of humour that has you pondering the self-description of this life-long pacifist years later.

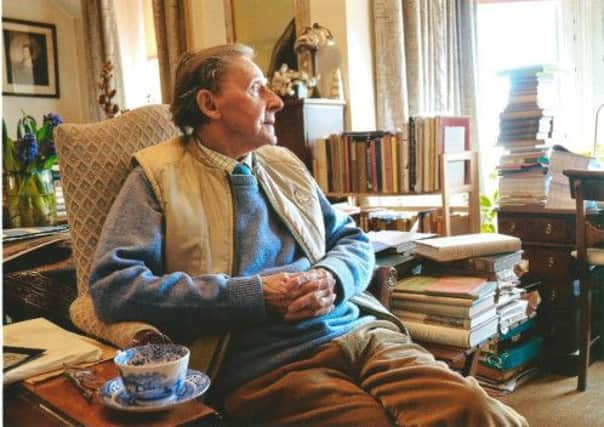

Edward Nairn was indeed born in Glasgow, to Edward King Nairn and Marion Gillespie, both professional musicians, his father a violinist and his mother a pianist. It was evident that, although not a practising musician, Nairn inherited from them a deep love and understanding of music, which in turn informed his love and appreciation of literature. But, as anyone who met him, bought from him, or visited him and his partner Ian Watson at John Updike booksellers knows, his visual sensibility was no less keen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNairn’s childhood was spent with his mother in the village of Tighnabruaich in Argyll, and his love of the natural world, of flowers and the landscape and of boats and seascape, must date from these early years. At primary school he won a prize for “best wildflower bouquet” – which won’t surprise those who have admired his wonderful window-boxes over the years, and the lovely arrangements which would appear in the flat in Edinburgh’s St Bernard’s Row after forays made into the countryside, with Watson driving and Nairn navigating.

Later academic distinction at his secondary school was recognised in his becoming co-Dux of the Hermitage Academy, Helensburgh.

Nairn’s first job was in the design department of Templeton’s Carpet Factory in Glasgow, but he did not much enjoy this and moved to Jackson’s Bookshop, also in Glasgow, a milieu where he must have felt more at home and where he started to make friends, notably with Christopher Grieve (better known by his pen name, Hugh MacDiarmid) and with the artist-poet Ian Hamilton Finlay, with whom he fire-watched during the Second World War, sharing interests and ideas as they watched, and reputedly reading Beckett on the roof of the Mitchell Library. Both these friendships remained close until death.

During the war, Nairn befriended many artists at Glasgow Council’s Refugee Centre, which the council set up to welcome refugees from Europe. Nairn was a conscientious objector, although his health would not have allowed him to serve in the armed forces in any case.

The 1940s were a fertile period for Nairn. He told Alistair Peebles of this time: “I can remember when I read Auden first. I hadn’t read modern poetry at all. I had gone to this marvellous library in Kilmarnock and taken out Look Stranger. It was a Saturday afternoon, and the train was packed with farmers and farmers’ wives and so on, falling asleep from the sun and everything.

“And I read this poem, and I had never read a poem like that in my life before. And I read it over and over, and I looked round the people because I felt they must see some change in me. That was what I felt. That I would look different after reading this poem.”

Although Nairn did not publish his first book of poems until he had turned 92, he appreciated and wrote poetry throughout his life. After Jackson’s Bookshop, Nairn became a publisher’s representative, travelling all over England and Scotland, and in latter years as he trawled the bookshops – even into his mid-nineties – he would always look out for the publications of William McLellan, no doubt buying back works of mid-20th-century Scottish literature which he had placed with booksellers more that 50 years before.

In the late 1940s Nairn and his mother moved to Edinburgh, as it was thought that she might benefit from the east coast air. Here Nairn met Kulgin Duval and they moved to London for a short while before returning to Edinburgh in 1948, at which point Nairn joined the staff of James Thin, then primarily a second-hand and antiquarian bookshop.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had many vivid memories of working at Thin’s, where he remained until 1954, even to remembering individual volumes and where they had been placed on the shelves all that time ago.

A notable customer was Charles Sarolea, the first head of the French Department at Edinburgh University and for more than 40 years the Belgian Consul in Edinburgh, who had to purchase a second and neighbouring four-storey house to make room for his expanding collection.

When the collection was sold Nairn recalled that “chutes came down from the windows of the two houses into pantechnicons and it took a team of boys three days to unload Thin’s share into the shop”.

At lunchtime he would be sure to leave the shop before the banks closed, not to draw or deposit cash as you might think, but because a local bank manager was another eagle-eyed collector and Nairn wanted to be sure to comb the “Book-hunter’s Stall” on the railings beside Greyfriars Bobby before he arrived. From 1954 until 1962 Nairn was in partnership with Kulgin Duval, working from a flat in Rose Street in central Edinburgh. They remained lifelong friends, but Duval moved into antiquarian books.

In the early 1960s Nairn met Ian Watson and in 1964 the partnership of John Updike Rare Books was formed, specialising in 19th and 20th century literature, private press and illustrated books and becoming universally recognised for the quality and condition of their stock.

Still resisting technology, the partnership has always kept up with prices and trends, and buying would involve whispered discussions as enthusiasm was balanced with shrewd business sense. With no formal shop hours to keep, Nairn and Watson were free to travel at will and passed up no opportunity to visit bookshops all over the country, combining buying trips with visits to friends, often artists, writers or musicians.

Hospitality was (and continues to be) eagerly reciprocated, and a visit to “the Updikes” has always involved a feast of books followed by a glass of something, a tea party and chat.

Nairn and Watson’s final tea party took place in the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh following their civil partnership ceremony, celebrating their partnership of nearly 50 years. Their mutual support enabled this partnership to thrive and ensured that Edward Nairn must have been one of the longest-serving members of the book trade ever. We extend our sympathy to Ian Watson, who will continue to trade alone as John Updike.