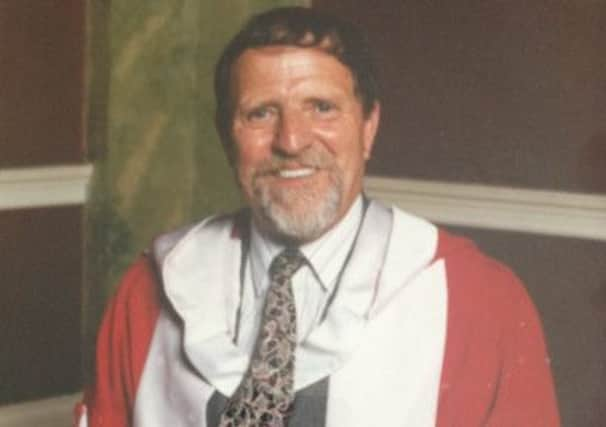

Obituary: Dr Joe Cross OBE

Joe Cross was a young naval airman when two events occurred that would change the course of his career and, ultimately, the international culture of safety at sea.

The first was a lesson learned during a crisis in a flooded life raft, in open water and worsening weather, when he discovered vital safety equipment was missing. The second was an air crash tragedy that claimed the life of his colleague with whom he had survived the life raft incident.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTogether they would put him on the path to what became the main focus of his working life for the next 40 years, lead to his founding of the International Association for Safety and Survival Training (IASST) and the development of leading-edge equipment that forms the core of today’s maritime survival training.

Cross, who headed Aberdeen’s Robert Gordon Institute of Technology (RGIT) survival centre when it introduced the world’s first helicopter underwater escape training facility, was awarded an OBE for his services to maritime safety and survival and remained honorary president of the IASST.

A Liverpudlian, he was the son of plasterer George Cross and his wife Winifred and at one point was expected to follow his father, who set up his own firm, into the building business. After leaving Merseyside’s Huyton Modern Senior School he enrolled on a building course at Bootle Technical College but it wasn’t for him and, during a spell working in a telephone manufacturing company, he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, before signing up for the Fleet Air Arm where he had hoped to become a photographer.

However, after initial training, the powers that be dashed that particular ambition when they decided he was to become a specialist in safety equipment. He subsequently qualified, in 1953, as Naval Airman 2 Safety Equipment 3. It was during the next couple of years learning his trade at HMS Gannet, a naval air station near Londonderry in Northern Ireland, that the two defining events took place.

The life raft drama happened when he was volunteered to take part in a sea trial to test a prototype downed aircrew location beacon. Along with a leading aircrewman, he left a destroyer on a none too pleasant day and watched the ship disappear over the horizon. The beacon worked perfectly but as they waited for a search aircraft to find them the weather deteriorated, with a worsening sea state, wind and heavy rain. On checking the raft’s survival kit, he found that the equipment, including the crucial bailer, was missing. They were marooned in a flooded raft in a breaking sea.

Fortunately the ship returned, rescued them and the trial was deemed a success. But Cross observed: “The lesson was learnt, survival at sea or for that matter elsewhere, often will depend on having good, reliable and available kit to meet the challenges of a developing crisis.”

Just a few weeks later, while working in the safety equipment section, he was ordered to attend the site of an air crash to collect the safety gear involved. He arrived to find the plane had hit a hill with the loss of all the crew, including the airman who had been his companion on the recent life raft adventure.

“That day I grew up quickly and to some extent dedicated myself to doing my best to learn all that I could about my ‘imposed profession’,” he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe rose through the ranks and in 1960 gained the top qualification in safety equipment and the rank of leading airman. Five years later he was promoted to sub lieutenant, special duties aviation, and appointed to HMS Victorious as assistant flight deck officer/project sight officer.

The following year saw him become a Fleet Air Arm combat survival and arctic cell officer, for the annual Northern Flank of Nato deployment in Norway, and in 1970 he was promoted to lieutenant.

Ironically, he was already fighting his own battle for survival – against ill health. He had cardiovascular disease and had already suffered a heart attack at the age of just 34. As a result, his service in the Royal Navy came to an end in 1973 when he was invalided out because of his condition.

He then spent a season running his own sailing school before moving to Aberdeen to join RGIT’s school of navigation, as a lecturer in offshore survival, in 1974. He was appointed managing director of the RGIT survival centre the following year and oversaw a period of enormous expansion in the industry. From only two staff working in a hut by the River Dee, it emerged into a multi-million pound business, with more than 100 staff and training many thousands of workers in the survival skills required to operate in the offshore energy industry.

The centre developed a major training facility in Aberdeen with the first simulator teaching trainees how to escape from a helicopter under water. There was also a freefall lifeboat training facility in Dundee. In 1980 he founded the IASST, to share best practice in maritime survival training around the world.

Cross, who also served on the Defence Services Lifesaving Committee, was made an OBE in 1986, received an honorary MSc from the Council for National Academic Awards in 1991 and was made an honorary Doctor of Technology by Robert Gordon University in 1995, the year before he retired.

Once a middle distance runner for Liverpool Harriers in his youth, he had defied his heart condition for the vast majority of his life, facing it with the same pragmatism and determination with which he had addressed survival and safety issues in both the Fleet Air Arm and offshore sector. In the 1970s, after his first coronary bypass, he was one of the early members of Inverurie Jogging Club as he battled back to fitness. He took up cycling in his 50s, found retirement a challenging state of affairs to come to terms with initially and latterly was an active member of Probus and a fan of classic cars, having owned two Morgans, which he used to drive to the south of France each year.

He moved home from Inverurie to Ballater just two days before he died and is survived by his wife Desna, children Martin, Greig, Desna and Samantha, 11 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

ALISON SHAW