Obituary: Dr Gerald Edelman, Nobel laureate

Dr Gerald Edelman shared a 1972 Nobel Prize for a breakthrough in immunology and went on to contribute key findings in neuroscience and other fields, becoming a leading if contentious theorist on the workings of the brain.

The precise cause of death was uncertain, but Edelman had Parkinson’s disease and prostate cancer, his son David said. Edelman was known as a problem-solver, a man of relentless intellectual energy who asked big questions and attacked big projects. What interested him, he said, were “dark areas” where mystery reigned.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Anybody in science, if there are enough anybodies, can find the answer,” he said in a 1994. “It’s an Easter egg hunt. That isn’t the idea. The idea is: can you ask the question in such a way as to facilitate the answer? And I think the great scientists do that.”

His Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine came in 1972 after more than decade of work on the process by which antibodies, the foot soldiers of the immune system, mount their defence against infection and disease. He shared the prize with Rodney Porter, a British scientist who worked independent of Edelman. The Nobel committee cited them for their separate approaches in deciphering the chemical structure of antibodies, also known as immunoglobulins.

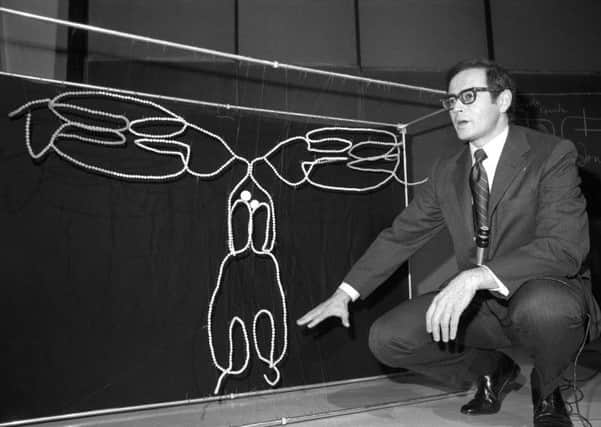

Edelman discovered that anti-bodies were not constructed in the shape of one long peptide chain, as thought, but of two – one light, one heavy – that were linked. From this, he and a research team at Rockefeller University in New York determined the structure of an entire immunoglobulin molecule. Their advance, as well as Porter’s, “incited a fervent research activity the whole world over, in all fields of immunological science”, the Nobel committee said.

From the mid-1970s on, Edelman was largely concerned with the brain and the nature of consciousness – “how the brain gives rise to the mind”, as he put it. He rejected the prevalent notion that the best model for the brain was a computer. Rather, he took a lesson from his earlier work in immunology. He had helped establish that antibodies work according to a process akin to Darwinian selection, and he now postulated a theory of the brain called neuronal group selection, which came to be known as “neural Darwinism”.

Within the dense thicket of nerve cells in the brain, known as neurons, are a vast array of neuronal groups. Edelman believed that when something happened in the world – something encountered by one of our senses – some neuronal groups responded and were strengthened by a series of biological processes. Those groups, he concluded, became more likely to respond to the same or a similar stimulus the next time, and thus did the brain learn from its own experience and shape itself.

Edelman discussed neural Darwinism and his theories connecting biology and consciousness in four books, including Bright Air, Brilliant Fire: On the Matter of the Mind (1992). They were received with both admiration and scepticism, praised as visionary by some and judged incomprehensible by others. Gunther Stent, a pioneer of modern biology, said: “I consider myself not too dumb. I am a professor of molecular biology and chairman of the neurobiology section of the National Academy of Sciences, so I should understand it. But I don’t.”

Since then, however, elements of Edelman’s work have been supported by experimental research. “To some degree it’s still an intractable subject,” said Peter Vanderklish, a neuroscientist and professor at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, where he and Edelman were colleagues. “There isn’t going to be any kind of theory of the brain that doesn’t involve elements of his ideas. The brain is never in the same state twice, and will never encounter the same environmental cues twice. What’s attractive about his model is that it tries to address that reality.”

Gerald Maurice Edelman was born on July 1, 1929, in New York City’s Queens borough. He grew up there and in Long Beach, New York. As a boy, he studied violin and considered becoming a professional musician. After graduating from Ursinus College in Pennsylvania, he earned a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and interned at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. From 1955 to 1957 he served in the US army medical corps in Paris, after which he began his research on antibodies at the Rockefeller Institute, now Rockefeller University.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere, in 1981, he founded the Neurosciences Institute. Much of its study of the brain is based on the theory of neuronal group selection and computer simulations of nervous systems. The institute later moved to the Scripps campus and in 2012 separated from Scripps and relocated nearby.

In addition to his son David, Edelman is survived by his wife, Maxine, whom he married in 1950; a second son, Eric; and a daughter, Judith.

Edelman was the author of hundreds of articles and papers. His books include A Universe of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination” (2000), written with Giulio Tononi, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist.

Tononi described Edelman in an interview as a major thinker whose ideas pushed science forward. As to the durability of Edelman’s ideas, he added: “The overall spirit has been vindicated. That’s how I would put it.”

• Copyright New York Times, 2014. Distributed by the NYT syndication service