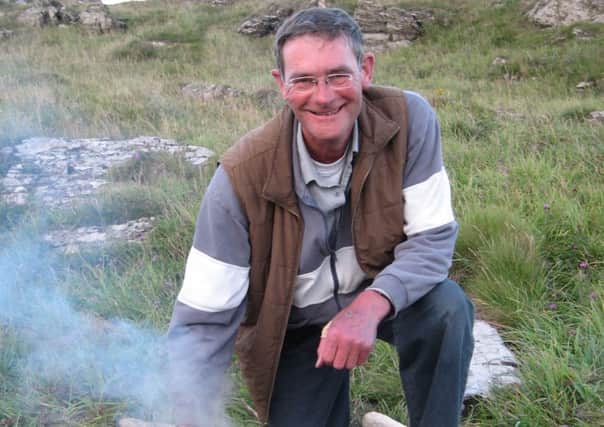

Obituary: Colin Murray, anthropologist and author

COLIN Murray, born in Edinburgh to a Borders family, was a distinguished social anthropologist, archaeologist and author best known for his field work in southern Africa and particularly in Lesotho. He had discovered the joys, and the tragedies, of Africa while teaching children in a school in the Ugandan bush during a stint with the international development charity Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO).

More recently, he was studying and writing about the social history of the tiny, barely inhabited tidal island of Ardwall (also known as Laurie’s Isle), one of the Isles of Fleet off Galloway in the north Irish Sea. He was particularly interested in the role of these islands’ families within the British empire in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough he worked and taught mostly in England, he and his family retreated every summer to the only cottage on Ardwall, owned by the McCulloch family, reachable on foot during low tide but otherwise by boat. His Ardwall project, on which he was working until illness took hold, looked into the role of Scottish families from the region who ended up playing significant roles in the British empire at its peak.

These included “free traders” (smugglers) off the coast of Galloway and Scottish doctors and tea plantation bosses in India. Some local mainlanders refused to go to Ardwall because of ancient stories that it was haunted but, according to Murray’s daughter Megan, it was on Ardwall that he found spiritual peace.

Colin Murray was born in 1948 in the Simpson Memorial Hospital in Edinburgh, at the time part of the Royal Infirmary. His father John was a retired naval officer, land factor and fruit farmer living at the time at Bonchester Bridge in the Borders.

His mother Anne (née Watson) came from a long line of Edinburgh lawyers. Her grandfather William Watson was Lord Advocate of Scotland and Lord of Appeal in latter half of the 19th century. She and John married in St Giles’ Cathedral in 1943.

Colin was educated first at Fyvie, Aberdeenshire, where his father was a land factor, but moved south on a bursary to Bryanston School in Dorset while his parents ran a fruit farm in Suffolk, spending their summers in Galloway and eventually retiring to Borgue, near Kirkcudbright, in 1979.

By then, Colin had already taught English and maths at a school near Rwashamaire in the south-west Ugandan bush before going up to Cambridge University (Fitzwilliam College).

He initially signed up for a degree in classics but his experiences with needy children in the African bush led him to switch to archaeology and anthropology. After graduating, he did several years of post-graduate field work in a village in Lesotho, where he learned the local language – known as Sotho or Sesotho – and became part of the family for the villagers.

In later years, he juggled fieldwork in Africa with teaching posts – in Cape Town, the London School of Economics and the universities of Liverpool and Manchester. In 1979, he married Yorkshire girl Linda Pepper and they had two daughters, Hannah and Megan.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough they later divorced, they remained good friends and Colin would later, in 2005, marry Jane Osgood.

His studies of migrant labour and forced resettlements in the still-apartheid South Africa were not without personal risk. He investigated the forced displacement of black South Africans from farms and towns, when he worked mostly in two large “reserves” (or slums) where displaced people were concentrated in the Orange Free State.

He was often questioned by suspicious South African security police and his visa exemption status as a British citizens was withdrawn for ten years.

Not to be deterred, he subsequently continued short field expeditions from Lesotho into South Africa, using his fluent Sesotho to chat up border officials and distract them from checking their list of prohibited persons.

These trips shifted his focus from more traditional anthropology to social history and political economy.

Thus was born his 1992 book Black Mountain: Land, class and power in the Eastern Orange Free State, 1880s to 1980s. His earlier book, Families Divided: The Impact of Migrant Labour in Lesotho (1981), had already become standard reading for students of anthropology, sociology and history.

Later, in 2005, he published, along with Peter Sanders, an important book titled Medicine Murder in Colonial Lesotho: The Anatomy of a Moral Crisis. It examined ritualised murders in Lesotho when it was a British colony (Basutoland), in which victims’ body parts were used for supposed medicinal purposes.

The book was considered a breakthrough in examining the moral crisis which emerged from the clash of local tribal and colonial mores and practices. For many years he was joint editor of the quarterly English-language Journal of Southern African Studies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdColin Murray had been diagnosed in the late 1990s with a rare auto-immune disorder known as Churg-Strauss syndrome, initially showing itself through atrial fibrillation (irregular heartbeat) and extreme lethargy.

He retired early in 2002 and settled in High Peak, Derbyshire, with his partner and future wife Jane. Although he was fitted with a pacemaker, vascular problems developed and he suffered a gradual decline until he died of heart failure in a hospice in Cheshire.

“We like to remember him with a popular farewell in the Sesotho language,” his daughter Megan said. “Tsamaea hantle, ntate (Go well).”

Colin Murray is survived by his wife Jane and his two daughters from his first marriage, Hannah and Megan.

PHIL DAVISON