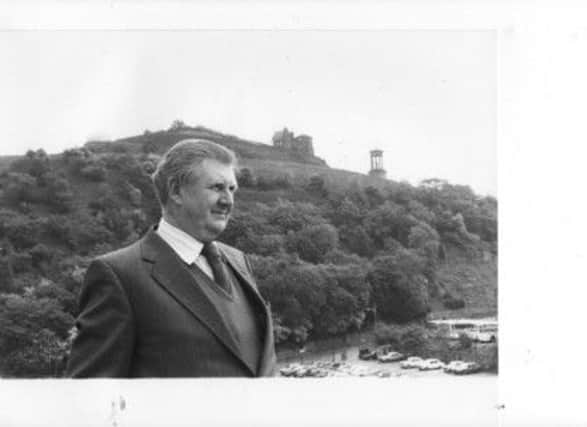

Obituary: Colin McDermott, engineer and arts campaigner

Born: 13 October, 1928, in Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. Died: 18 February, 2014, in Carlisle, aged 85.

Although others were involved (notably the Playhouse Preservation Action Group, an offshoot of the Scottish Theatre Organ Preservation Society), it was when Colin formed the Edinburgh Playhouse Society that things began to happen.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA letter he wrote to The Scotsman on 12 March, 1975 produced some very supportive responses, and four months later Colin called the first meeting of what then became the Playhouse Society.

Colin McDermott was born in Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire on 13 October, 1928. Prophetically, it was the year the Playhouse was scheduled to open.

He studied engineering in Manchester and Bristol and moved to Edinburgh in 1957 to work with Ferranti’s. A keen amateur musician who was leader of his school orchestra, he was attracted by the thought of living in a city with a reputation for music and culture.

By 1974 he was busy building up a specialist team working on advanced satellite and space vehicle navigation instruments for the US Navy.

I recall a piece written by Neville Garden in the Scottish Daily Express which began along the lines of: “By day he designs the nose cones for killer rockets. By night he is better known as the benign phantom of the opera . . .”

In the 1970s the Empire (now the Festival Theatre) and the King’s were used for both opera and ballet. The Empire’s large stage and 2,000-seat capacity was complemented by the smaller stage and 1,200 seats at the King’s.

However, when the Empire closed, Edinburgh was left without a large-scale theatre.

At that point, attention turned to the thought of a new building suitable for opera and ballet.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe District Council already ran the Lyceum Theatre, the Usher Hall and the King’s Theatre. The councillors were heavily committed to the idea of a new “opera house” in Castle Terrace, but the budget for this project was already over £4 million.

At that point the UK Government, which had agreed to fund part of the project, withdrew its offer of financial support.

A feasibility study suggested that after allowing for a traditionally sized stage and back-stage facilities there would only be room for 1,200 seats – the same size as the King’s. And the auditorium would be too small to suit the acoustics needed for opera performances.

The Playhouse, on the other hand, was originally designed as a theatre (modelled on The Roxy in New York). With 3,023 seats it was the biggest theatre in Britain, and the acoustics were suitable for opera performances.

The choice was between a hugely expensive new building at some point in the future, or converting a well-designed old building as a temporary or even permanent alternative.

The Playhouse Society organised a 13,500-signature petition to save the theatre, and presented it to Edinburgh District Council and the newly formed Lothian Regional Council.

Feelings ran high. At various times the District Council, the Scottish Arts Council, the Scottish Office and the directors of both Scottish Opera and the Edinburgh Festival were all against the plan to re-open the Playhouse.

They were confronted by one pesky Yorkshireman and the members of his committee.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnly Lothian Region showed any interest in the project. The society appointed professional fund-raisers and PR consultants, and persuaded Edinburgh Council to grant temporary performance licences for shows organised by Scottish Television, including performances by Elton John and Billy Connolly.

A “Music from the Movies” concert featured English National Opera soloists Rita Hunter and Ann Howard.

Meanwhile, the society committee started a nationwide lobbying campaign to gather support. The members contacted the Royal Opera, English National Opera and all the major ballet companies, and assembled an impressive list of patrons. They included Yehudi Menuhin, Sir John Betjeman, Ronnie Corbett, Peter Darrell, Spike Milligan, Magnus Magnusson, Gian Carlo Menotti, Patrick Moore, Malcolm Rifkind, Moira Shearer, Sir Michael Tippett, Sir Charles Groves and Dorothy Tutin.

Apart from talking to potential patrons, the society commissioned professional reports about how the theatre could work as an opera house.

One of the most significant was from Richard Condon, manager of the profit-making Theatre Royal in Norwich. His report on the Playhouse was glowing. He predicted that the theatre could be to Edinburgh “what North Sea oil was to the UK”.

Armed with this, The Playhouse Society arranged to make a presentation to Edinburgh Council. The reception was negative. The Labour members of the council walked out before anyone had spoken, and Richard Condon was allowed to speak for four minutes to a silent chamber.

At that point the chairman closed the meeting without discussion.

Part of Richard Condon’s fund-raising strategy in Norwich was a weekly lottery, and the Playhouse Society decided to take up the idea.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough the purchase price of the theatre was only £130,000, a preservation order placed on it meant that any new owner would have to maintain the building as a theatre and pay for a substantial amount of restoration and upgrading, as well as underwriting the ongoing running costs.

These figures were well beyond the Playhouse Society’s reach, but Lothian Region was persuaded by the viability reports and agreed to buy the building.

The society’s main interest – and the reason for starting the campaign in the first place – was to have a theatre which would work for opera and ballet performances. A key missing component in the plans was for an orchestra pit big enough to hold a full orchestra of up to 110 musicians. The society’s lottery raised most of the money for this, and the pit was used for the first time on 6 June, 1980 for a performance of Rigoletto by Scottish Opera.

The Edinburgh Playhouse Society may not have been able to buy the building, but the untiring work and fund-raising by Colin McDermott and the other members secured the future of the theatre for large-scale musical shows, adding an extra, lasting resource to the cultural life of Edinburgh.

The campaign to save the Playhouse is detailed in Colin’s book The Saving of the Playhouse Theatre 1973-1983.

Colin retired from Ferranti in 1989 and moved to Allendale, near Hexham in Northumberland, where he set up a series of annual concerts, Music in Allendale, with Sir Thomas Allen as patron.

He is remembered with affection by his fellow campaigners as someone with “a pretty good bulls**t detector” and a “well-developed curmudgeon act”. He was well able to stand up for himself and his pet project against negative elements in the local authority, the then theatre management, and occasionally even from members of the Playhouse Society Committee.

Colin is survived by his former wife double bass player Jane.