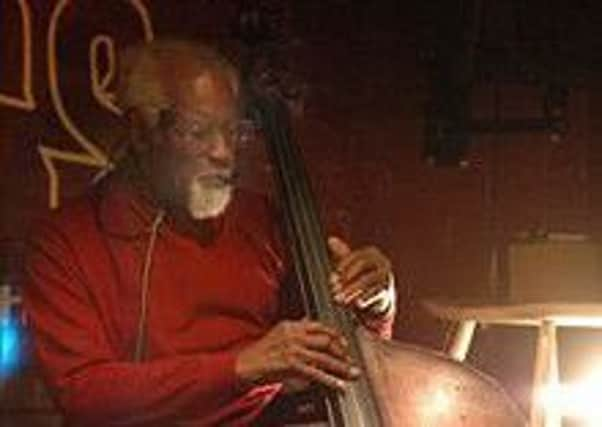

Obituary: Coleridge Goode, musician

Jamaican-born jazz double-bassist Coleridge Goode was a stalwart of the British post-war jazz scene for almost 70 years, playing and recording with some of the industry’s most innovative giants, including Django Reinhardt, Ray Ellington, Stéphane Grappelli and Joe Harriott, an experience he described as among the “greatest musical adventures of my life”. He was also credited as one of the creators of British avant-garde “free jazz” with his influence reaching deep into European jazz as well as inspiring many of today’s contemporary black British jazz musicians.

Goode’s rich, full tone, flawless timekeeping, effective swing and, above all, his ability to supply the appropriate nuance and flourish to the more challenging abstractions of a piece, meant that he was never out of work and always in demand, performing in the house band at Laurie Morgan’s Sunday jam sessions at the King’s Head in Crouch End, London, well into his nineties.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdColeridge George Emerson Goode was born in 1914 and grew up in Jamaica with his two sisters. His mother, Hilda, sang soprano in the Kingston parish choir, while his father, George, was a choirmaster and organist, whose interest in poetry and music filled a specially designated room. Consequently, young Coleridge was named after the celebrated black composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and “Emerson” came from the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, and grew up listening to the works of European composers such as Handel and Bach.

As a boy, Goode learned the violin, in which he excelled, while attending Calabar High School, but also showed an interest in motorbikes, riding, stripping them down and rebuilding them. In 1934, aged 19, he took the momentous decision to sail to the UK to study electrical engineering. Arriving in Bristol, he travelled to Glasgow, where he was shocked to be the only black face. He attended the city’s Royal Technical College (now the University of Strathclyde) as his father had corresponded with the head of the music department, before moving on to complete his degree at the University of Glasgow.

During this period, however, Goode had joined the university orchestra and discovered jazz, taking up the double bass after hearing the music of Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday. For him it was a “eureka” moment, realising that electrical engineering would not be his future, although he did continue to tinker with electrical and electronic devices, building television sets for friends and later assembling his own bass amplification system, which combined with a microphone enabled him to sing and play simultaneously, based on the style of the American bassist Slam Stewart.

With Britain at war, in 1942, Goode headed south to London to pursue his dream of becoming a professional musician. The capital was awash with jazz clubs and, with American GIs about, jazz was thriving and soon Goode was in demand in small Caribbean clubs and West End venues such as the Panama Club. In his autobiography, Bass Lines (2002), he recalled: “The war got rid of all the stuffiness.”

Goode joined a number of bands including the popular band the Claepigeons, led by the Anglo-Belgian trumpeter and amateur racing driver Johnny Claes, and a trio consisting of the pianist Dick Katz, the guitarist Lauderic Caton and himself on bass. In later years, he entertained friends with stories about how he and the band’s blind drummer, Carlo Krahmer, transported their bulky instruments on the underground during the Blitz. He was later a member of the original Ray Ellington Quartet and swiftly progressed to recording sessions with some of the most exciting talents on the jazz scene.

In 1943 he met Gertrude, a Jewish refugee of Hungarian origin from Vienna, and after a whirlwind romance, they married in January 1944; they remained together until her death in June this year.

Post-war, Goode played for the reunion of the French violinist Stéphane Grappelli, who had been in London during the war, and Franco-Belgian guitar legend Django Reinhardt, with whom he became good friends, sometimes staying at the family’s London flat; he played on the original recording of Reinhardt’s jazz standard, Belleville, in 1946. With Grappelli, Reinhardt co-founded the Quintette du Hot Club de France, described by critic Thom Jurek as “one of the most original bands in the history of recorded jazz”. Goode, its last surviving and only ever Caribbean member, played on Reinhardt’s immortal recording of Nuages.

Over the years Goode also played and recorded with the pianist George Shearing, the Tito Burns’ sextet, led his own group and was a founder member of the Ray Ellington Quartet led by its enthusiastic drummer and singer. Shearing left for the US where he was a huge success but Goode was never inclined to go after his experience of American soldiers’ racist behaviour while stationed in London.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdViewed by Goode as the zenith of his career, in the 1950s he joined fellow Jamaican and forward-looking musician, alto sax Joe Harriott. Although demanding and pushy, Harriott’s new and radical conception of free-form and later Indo-Jazz Fusions, with Indian violinist John Mayer, got the best out of his musicians with Goode particularly thriving on the challenge. The upshot was spell-binding albums, including Free Form (1960), Abstract (1962), Movement (1963), and High Spirits (1964).

In the 1960s and 70s, Goode worked extensively with English pianist-composer Michael Garrick and contributed a fine vocal in the manner of Leroy “Slam” Stewart to The Lord’s Prayer on Garrick’s 1968 album Jazz Praises. Working on this, Goode wrote, “brought me right back home… because it reminded me of my father’s work as an organist with choirs”.

Mild-mannered and self-deprecating, Goode was regarded as one of the finest jazz bassists to have worked in Europe, and was an important link to a rich heritage of Caribbean music. His achievements over a 70-year career have been an important inspiration for some of Britain’s leading contemporary black jazz musicians such as double bassist, Gary Crosby.

In 2011 Goode received a Parliamentary Jazz Award for Services to Jazz and at his centenary was honoured with a special event at the 2014 EFG London Jazz Festival led by Gary Crosby.

Goode is survived by his daughter, Sandy, and son, Jim.