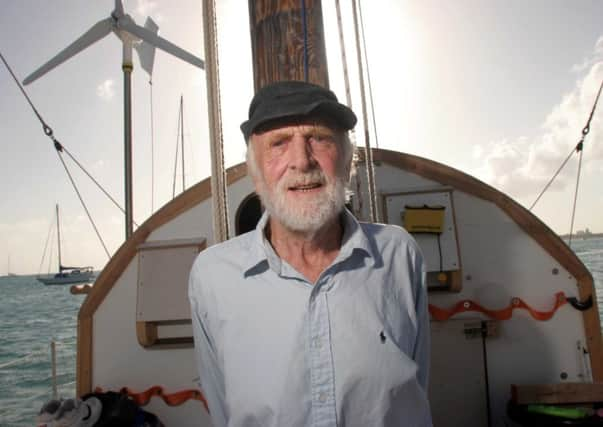

Obituary: Anthony Smith, explorer and journalist

‘Fancy rafting across the Atlantic? Famous traveller requires 3 crew. Must be OAP. Serious adventurers only.”

So read a help-wanted ad in The Daily Telegraph on 28 January, 2005. The ad was no joke. The man who placed it, Anthony Smith, then 78, was an explorer and author who had crossed the Alps by balloon and traversed Africa by motorcycle, among other things.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor his newest adventure, he was seeking old-age pensioners to cross the wild Atlantic with him on little more than a pile of logs. Smith, who died on 7 July at 88, made that voyage, but not before a strenuous campaign to raise money; a prolonged effort to build his strange, seaworthy craft; and a crippling accident that nearly cost him the use of his legs.

By the time he and his comrades finished their journey in 2011 – a 66-day odyssey in which they braved storms, were blown far off course and endured significant damage to their raft –Smith was 85.

They called their raft Antiki, partly in homage to Kon-Tiki, the raft on which Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl sailed the Pacific in 1947, partly in tribute to their own comparative antiquity. At journey’s end, the combined age of the Antiki’s crew was 259.

The crossing was not Smith’s last ocean adventure, nor even his most arduous. But it was undoubtedly his best known, minutely chronicled in the news media and through blog posts written mid-ocean by Smith and his crew.

It was also a crowning achievement of a career so bold that in the 1960s Smith, feared lost on a balloon voyage over Africa, had the dubious privilege of reading his own obituary.

Smith undertook the Atlantic crossing, he often said, to honour the credo, “Old men ought to be explorers”, from TS Eliot’s Four Quartets.

“Am I supposed to potter about, pruning roses and admiring pretty girls, or should I do something to justify my existence?” he said in 2011.

But he made the trip for another reason, equally compelling: to discharge a debt of honour that had tugged at him for more than half a century.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnthony John Francis Smith was born in 1926 in Taplow, in Buckinghamshire, and grew up there at Cliveden – Lord and Lady Astor’s estate – where his father was employed as the manager. After serving as a pilot with the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve in the 1940s, Smith earned a degree in zoology from Oxford.

His adventures began in his student days, when he and several classmates travelled to Iran in the summer of 1950 in search of a fabled eyeless white fish, said to inhabit the qanats, ancient irrigation tunnels there.

They did not find it, but the trip gave Smith his first book, Blind White Fish in Persia, published in 1953.

His later books include High Street Africa (1961), which chronicles his five-month journey, much of it by motorcycle, from Cape Town to England; Throw Out Two Hands (1966), about crossing East Africa in a hydrogen balloon in 1962 (the balloon was thought to have exploded during the trip, and at least one British paper published Smith’s obituary); and A Persian Quarter Century (1979), in which Smith returned to Iran and discovered his storied fish – the blind cave loach, later named Nemacheilus smithi in his honour.

But the Atlantic always loomed. He had hungered to cross it under sail since he was a youth, when he read Two Survived, a 1941 history of men who had made the journey and barely lived to the tell the tale. The book, by Guy Pearce Jones, recounts the fate of the British merchant ship Anglo Saxon, sunk by an armed German ship in 1940.

Seven seamen survived, escaping into the Atlantic in an 18-foot wooden craft known as a jolly boat. During their 70 days at sea, five died. Finally, after almost 3,000 miles, the two survivors – Roy Widdicombe, 21, and Robert Tapscott, 19, both near death – made landfall at Eleuthera, in the Bahamas.

Smith had long wanted to reprise the voyage in tribute to his two courageous countrymen, but he was waylaid by his professional life: he was a science correspondent for The Telegraph and later presented science programmes on British radio and television.

Then, at the dawn of the 21st century, just when conventional wisdom dictated he should settle down among the roses, Smith revived the idea.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe chose to go by raft for a practical reason: a raft, he said, was more stable than a boat.

On 30 January, 2011, the Antiki set sail from the Canary Islands stocked with three dozen tins of baked beans, several bottles of single-malt whisky, pasta, bananas and “a colossal pumpkin”, as Smith described it in one of his weekly dispatches to The Telegraph.

Its navigational gear, a satellite phone and a computer were powered by a wind generator, solar panels and a foot pump.

The raft had no motor; its single sail flew from a telephone pole.

Smith’s crew, though not as antique as he, was bereft of callow youth. The skipper, David Hildred, from the British Virgin Islands, was 57; the raft’s doctor, Andrew Bainbridge, from Canada, was 56; the fourth crewman, John Russell, an English lawyer, was 61. The Antiki was a matchbox on the sea.

“There is an awful lot that could come our way – storm, unhelpful changes in wind, raft failure of any kind, whales of less gentle disposition,” said Smith in a mid-voyage interview.

On the third day, two rudders broke, though the crew managed to jury-rig replacements. Three times, winds blew the Antiki hundreds of miles in the wrong direction; the raft’s average speed was 2.1 knots – about 2.4 mph.

On 6 April, 2011, the Antiki made land at St Maarten, in the Leeward Islands. Smith had hoped to land at Eleuthera as the sailors he honoured had done, but the winds dictated otherwise.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 2012, Smith completed the St Maarten-to-Eleuthera leg aboard the Antiki with a new crew, a 700-mile journey that entailed high winds and savage seas.

Smith’s two marriages, to Barbara Newman and Margaret Ann Holloway, ended in divorce. Survivors include two sons, three daughters and a grandson.

Widdicombe, who survived the sinking of the Anglo Saxon, died in 1941; his shipmate Tapscott died in 1963. In the 1990s, Smith helped arrange to have their jolly boat, which had long lain in storage at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, repatriated to the Imperial War Museum in London.

Smith’s memoir of the Antiki’s voyage, The Old Man & the Sea, is scheduled to be published next year.