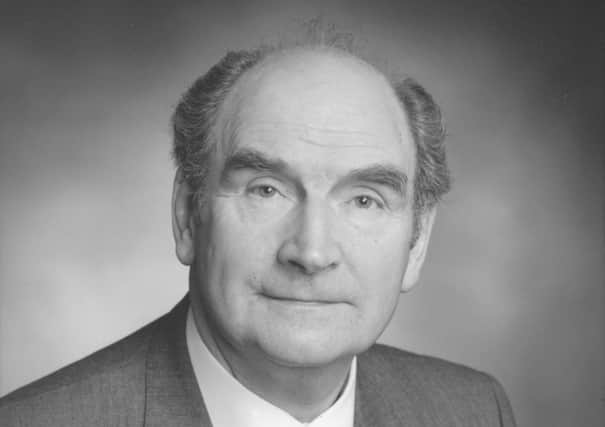

Obituary: Andrew Douglas MB, ChB, FRCP (Edin), physician

Andrew Douglas was born into a small Fife mining community. The youngest of a large family, he was the first to go to university, qualifying as a doctor and winning the Wightman Prize for Clinical Medicine at the Medical School in Edinburgh in 1946.

After his two pre-registration jobs at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and military service as officer in charge of the Field Ambulance Training Centre of the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR), he spent time as a GP before becoming a lecturer in Bacteriology at the University of Edinburgh and assistant bacteriologist at the Royal Infirmary. In 1952, during this appointment, he passed the examination to become a member of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnxious to return to clinical medicine, he moved into respiratory medicine in 1953, working at the City Hospital and the Northern General Hospital with John Crofton, Ian Grant, Norman Horne and Ian Ross.

In so doing he became part of the group of chest physicians and bacteriologists in Edinburgh, who made major contributions to establishing a drug regimen which, for the first time, could cure tuberculosis.

Heady and exciting days they were, but nevertheless days of very hard work and long hours.

In 1963 he was appointed senior lecturer in the Department of Respiratory Diseases at the City Hospital, a department which rapidly became world famous. Andrew’s clinical, academic and administrative contributions were a vital part of that department’s success.

He was elected a Fellow of the Edinburgh College in 1965, by which time he had developed a special interest in sarcoidosis and had rapidly acquired an international reputation in that and other granulomatous lung diseases.

For several years he was a member of the International Committee on Sarcoidosis and was a regular contributor at its conferences.

With John Crofton, he co-authored in 1969 the Textbook of Respiratory Diseases, the first major British textbook of the post-war era on this subject, which over many editions and for many years stood alone as the national and, to a large extent, international bible of the specialty. This was an enormous task in those pre-internet days of longhand, typewriter and hard copy.

In the mid-1970s, by popular request, he moved base to the Royal Infirmary to strengthen the respiratory service on that site, where he later became reader in the Department of Medicine and a physician whose opinion was much sought and greatly valued.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1986 he was awarded the Royal College’s Cullen Prize, a “Prize for the greatest benefit done to Practical Medicine”, thereby joining an elite which included such legends as Sir Robert Philip (1910), Sir Stanley Davidson (1938), Sir Derek Dunlop (1954) and Dame Sheila Sherlock (1962).

The regard in which he was held by colleagues and senior managers in the NHS was emphasised by his appointment as chairman of the Merit Award Committee of Scotland, an office which he performed diligently, perceptively and fairly.

He was president of the Scottish Thoracic Society (1980-82), which he had loyally supported since joining in 1950. In June 1982 he presented a memorable history of the early days of the society, a time when it had been the Tuberculosis Association of Scotland.

Characteristically, the lecture was meticulously researched and presented. He was president of the newly formed British Thoracic Society in 1984. His Presidential Lecture, “Promises to Keep”, held the society spellbound, a feat he frequently repeated when giving clinical and after-dinner talks during the society’s meetings with the Australian Thoracic Society in Adelaide and Sydney in 1984.

His soft Scottish tone, humour, expertise and humility had audiences eating out of his hand there and on his invited sabbaticals to North and South America. In 2001, in honour of his outstanding contribution to the specialty, he was awarded the British Thoracic Society’s Medal.

Andrew was, above all, a superb doctor – a physician of excellent clinical skills whose genuine interest in patients was evident to all who knew and worked with him.

He made each patient feel special, his remarkable memory for their family details and interests endearing him to them. He worked extremely hard in caring for his patients to a very high level and in a very personal way. There were no airs, no posing.

He will be remembered also as an outstanding teacher. His method was based on his immense clinical experience, liberally embellished with anecdotes and some favourite turns of phrase, many of which those he trained have subsequently used in their own practices.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe took a genuine interest in his juniors and in doctors visiting from overseas, most of whom became lifelong friends and stayed in regular touch with him and Helen, whom he had married in 1949 after a period as a lodger in her parents’ house.

Theirs was a close marriage, lasting almost 65 years. Always loyal, but not beyond telling him off when he tried her patience, Helen’s unstinting and devoted support was vital to his career and achievements. So many of the ornaments, pictures and tapestries in their home carried stories of overseas visitors and visits, which Andrew would tell in unique style as you unsuspectingly sipped a gin which had only gently been flavoured with tonic.

With Presbyterian moderation in respect of their own consumption (Andrew had for many years been a lay preacher and Elder), they were generous and warm hosts indeed.

Aside from medicine, he had an unquenchable appetite for knowledge of all sorts, but roses and his rose garden were his passion.

His knowledge of the flowers was comprehensive – well illustrated some years ago when he gave a memorable talk to the Edinburgh Medical-Chirurgical Society on “The history of the rose”.

On ward rounds, if he saw roses by the bedside, he would sample their fragrance and expertly name them, a welcome diversion from the serious business of the round.

On learning of his death, one of his colleagues aptly said that Andrew was “a dear man”.

This summarises the essence of the best physician and teacher I have known, and whose pupil and friend I was proud to be.