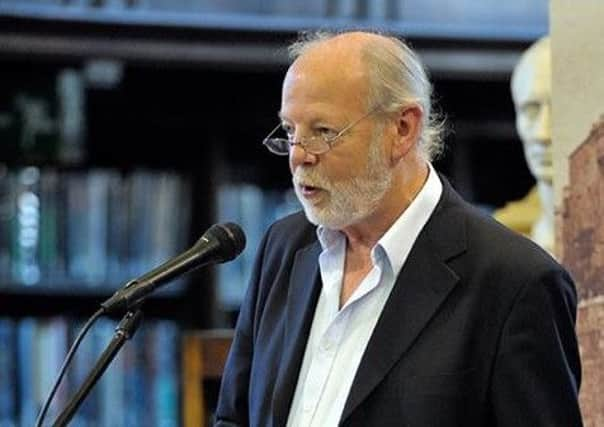

Obituary: Alexander Hutchison, poet and teacher

International and profoundly Scottish – that was how one reviewer summed up Sandy Hutchison’s last poetry anthology. It was also a description that reflected the man himself.

With his roots in the tight-knit fishing community of the North-east coast, he might easily have followed generations into the business and associated trades. But a love of literature, fuelled in boyhood by a family legacy of an extensive library, set him on a transatlantic course and, ultimately, international recognition as a writer, in both English and Scots, and teacher.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe spent almost two decades in North America, arriving at the age of just 22 to teach students only a couple of years his junior. He went on to international acclaim and, after returning to home, his talents were recognised with the award of a Royal Literary Fund Reading fellowship at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland followed last year by The Saltire Scottish Poetry Book of the Year prize, “an unexpected pleasure” he said of the accolade.

Born in Buckie, on the Moray Firth coast, the son of Margaret and Gordon Hutchison, both sides of his family had strong fishing connections. His maternal grandfather and great-grandfather were businessmen whose success was built on the booming herring industry of the time and his paternal grandfather had been involved in a salmon fishery at the mouth of the River Spey.

But the acquisition of a large selection of books from one his grandfathers gave young Sandy access to literature and poetry from an early age. The youngster could recite Kipling’s Gunga Din off by heart when he was still at Buckie Primary School. Then, after attending Buckie High School, he went up to Aberdeen University to study English and psychology.

On graduating with a joint honours degree, he was offered a job teaching English at the University of Victoria in Canada’s British Columbia. When he arrived to take up the post in 1966, he was still only 22 and the students apparently gasped at the image of the bright, handsome young man who walked in to take his first class.

In the early 1970s he was accepted at Northwestern University, Chicago, to do his PhD on the poet Theodore Roethke and did not return to teach at Victoria University but later commuted weekly to North Island College at Campbell River where he taught for seven years.

His first book of poetry, Deep-Tap Tree, was published by the University of Massachusetts Press in 1978 and remains in print. And among his first students was American poet August Kleinzahler, who, along with other writers and colleagues, remained a lifelong friend.

Hutchison who, during his work in North America, had also spent time in San Francisco on various occasions, returned to Scotland in 1984 following the break-up of his first marriage and his mother’s declining health. He had aimed to spend two years here before going back to Canada but he ended up staying, living in Edinburgh for seven years before moving to Glasgow.

He taught at the University of the West of Scotland and after retiring in 2010 was offered the Fellowship at the Royal Conservatoire, a post he thoroughly enjoyed. It was also in 2010 that the Italian literary magazine In Forma Di Parole dedicated an issue to his work. It featured translations of his poems plus Hutchison’s versions of the works of Latin poet Catullus and leading Italian intellectual Pier Paolo Pasolini in English and Scots

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs well as being widely known in Canada, the USA and Italy, his work was also appreciated in Nicaragua where he was involved latterly with the Festival Internacional de Poesia de Granada. Again his poems had been translated and he also turned two works by the Nicaraguan theologian, poet and politician Ernesto Cardenal into Scots. After attending the festival earlier this year he flew to New York where he was the main guest at a poetry dinner in Manhattan, talked to students at top prep school in Massachusetts and gave a seminar at a State University of New York campus on Long Island.

Following his trip to Nicaragua, when he briefly met Cardenal, he discussed the visit and his writing with Creative Scotland, acknowledging the changes in his field over the years due to rapid advances in technology and the way poetry has created new audiences. “In some ways I have adapted to new things, in others I have just cranked steadily along. I enjoy reading my poetry in all the new venues available and have opted sometimes to write stuff I know will stimulate interest for particular audiences. But making a whole sound, and putting it out as real sound in the air, has always been a key aim.”

Poetry had been a main element in his life for as long as he could remember and his bibliography included The Moon Calf (1990), Carbon Atom (2006), Scales Dog: New and Selected Poems (2007) and Bones & Breath (2013), the latter winning him The Saltire poetry award for what judges described as “a collection that savours the music and heft of language, including and especially Scots”.

And just days before he died, Gavia Stellata, a book of his poems translated into Spanish by Juana Adcock, was issued by a Mexican publisher, confirmation of the allure of his poetry around the world.

He is survived by his wife Meg Stiven, daughter of Scottish Poetry Library founder Tessa Ransford, daughter Lucy and son Max.