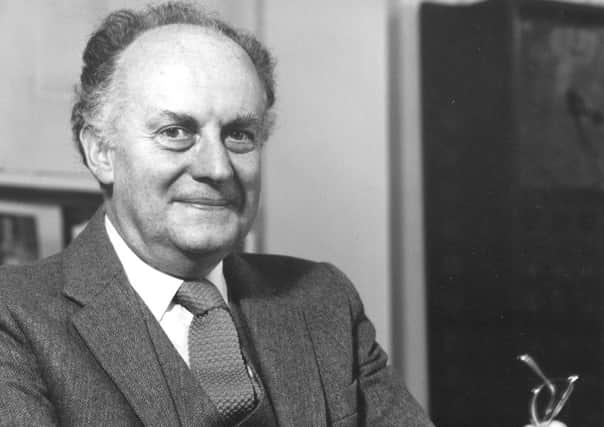

Appreciation: Bill Buchanan, champion of the visual arts in Scotland for more than a quarter of a century

It is difficult, in a limited space, to do full justice to the achievements of Bill Buchanan, who died on 4 September. As the Art Director of the Scottish Arts Council, and as Head of Fine Art at Glasgow School of Art (where he also served as Acting Director), he was, for more than a quarter of a century, a powerful and influential champion of the visual arts in Scotland.

Born in Trinidad in 1932, William Menzies Buchanan studied at Glasgow School of Art and taught in Glasgow schools for five years. In 1961 he joined the Scottish office of the Arts Council of Great Britain, which became the Scottish Arts Council (SAC) six years later. At this time the over-arching power of the Royal Scottish Academy was already in decline, and the newly formed and independent SAC rapidly assumed the leading role, offering grants to artists and financial support across the entire spectrum of art practices in Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was at the SAC, first as Exhibitions Officer and later as Art Director, that Bill began to demonstrate the qualities that were to characterise his professional life – a sympathetic understanding of those he worked with, originality of thinking and a willingness to take risks in support of his well-informed convictions – all carried off with a disarming modesty and understatement. He organised many groundbreaking exhibitions, such as New Painting in Glasgow 1940-46 (1968) and Robert Adam and Scotland – the Picturesque Drawings (1972).

He presided over an astonishing period of development of the visual arts in Scotland, overseeing an entire raft of new schemes and funding possibilities. Unique to Scotland was the revival of printmaking, which saw the opening of the first Printmakers’ Workshop in Edinburgh in 1967, followed in the Seventies by sister organisations in Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen. Many major new galleries were opened at this time, including the SAC’s own exhibition space in Charlotte Square, Edinburgh, the Fruitmarket Gallery, also in Edinburgh, and the Third Eye Centre in Glasgow.

It would be foolish, however, to give the impression that Bill’s job was an easy one, or that all was sweetness and light. The SAC’s art department had recruited several new members of staff, all eager to make their mark as exhibition organisers, and this often produced tension. It was Bill’s task to find ways to accommodate their sometimes over-ambitious projects. But then, culture wars were very much a part of the Scottish art world at that time. For many, the SAC had become an all-powerful establishment, and the disbursement of funds was scrutinised and argued over as never before. The RSA was a continuing “thorn in the flesh” and a battle ensued with artist Ian Hamilton Finlay. A particular bone of contention was the withdrawal of funding for the Ceramic Workshop in Edinburgh in 1975, and the unsuccessful battle that ensued in trying to reverse that decision led to the formation of the Federation of Scottish Artists. Its mission was to confront the SAC to seek changes in its policies and priorities.

On a personal level, Bill had other great passions that throughout his life absorbed his energies and demonstrated his capacity for innovative thinking, such as the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the history of Scottish photography. In 1970, with Katherine Michaelson of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, he organised the revelatory exhibition of the calotypes of David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. For this, he managed to persuade the Free Church of Scotland to lend Hill’s mammoth “Disruption” painting, something no one had managed previously.

As well as contributing to numerous magazines and other photographic publications, Bill was Chairman of Stills Gallery from 1987 to 1992.

He was also the prime mover behind a major conference that was staged at the Glasgow Film Theatre in March 1983 entitled Scottish Contributions to Photography. It was a mould-breaking event, and in its three days reached well beyond Scotland, as the list of participants demonstrated – a roster of the most important photo-historians of the time, including Mike Weaver from Oxford and Larry Schaaf from Baltimore.

In his room in the now devastated Glasgow School of Art, Bill hatched the idea of creating a permanent forum for study and promotion of photography in all its forms in Scotland. Thirty-five years later, the Scottish Society for the History of Photography is still a thriving organisation with its own distinctive and widely respected journal.

In the mid-Sixties, Bill created the conditions for Andrew McLaren Young’s extensive and illuminating research into the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh to be finally presented to the public, and the centenary exhibition that came about as a result was the smash hit of the 1968 Edinburgh International Festival. He commissioned an accompanying film on Mackintosh, in the process propelling its director, Murray Grigor, into a distinguished career in filmmaking on architecture.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1977 he returned to Glasgow School of Art, first as Head of Fine Art and later as Deputy Head and then Acting Head of the School itself. As Head of Fine Art, he brought to bear his core conviction in the power of art as a life-affirming force and his powerful, empathetic understanding of the creative process. These convictions were deployed in his negotiations with the then Scottish Education Department (SED) on his plans for the development of Fine Art at GSA, always presenting a logical and irrefutable case. His vision, honesty and integrity won the trust of the SED.

He engineered the founding of three new departments in Fine Art. The first, in 1983, was Fine Art Photography, recognising that photography was now accepted as a fine art practice in its own right. In 1985 he established the department of Environmental Art, which responded to the growing understanding of art as something that could be made and exhibited, not only for galleries and museums, but also in other more public locations. Finally, in 1988, he spearheaded the establishment of a two-year, full-time Master of Fine Art postgraduate course.

In increasing the portfolio of courses that the School offered he added a breadth and richness to the School of Fine Art, and, with the fine-tuning and strengthening of the existing disciplines of Painting, Printmaking and Sculpture, set the School on its course to the wide international reputation it enjoys today.

Nor should it be forgotten that Bill was passionate about the Art School building itself. It is said that when he began working at the School he insisted that only the flowers that Mackintosh had favoured in his designs should be used in his office.

Again he deployed his persuasive skills in negotiating with St Andrew’s House for a major investment in the Mackintosh heritage. His own contribution to that heritage was as the editor of and chief contributor to the book Mackintosh’s Masterwork (1989), which remains the standard work on the building.

With the sudden, unannounced departure in 1991 of John Whiteman, the recently appointed Director of GSA, the School governors turned to Bill Buchanan, confidant that he would provide the leadership and vision needed for the School to the face the clearly very challenging times that lay ahead. He did precisely that, and continued to steer Glasgow School of Art through the choppy waters of late 20th-century art education until his retirement in 1992.

He and his wife Alison went to live at Allan Water eight miles south of Hawick. There, he delighted in every phenomenon of the countryside and recorded what he saw in haikus in a classical Japanese format, which he exhibited as large prints. They were happy years, tragically cut short by Alison’s untimely death from breast cancer. Bill couldn’t stand the place without her and moved to Edinburgh. Meanwhile, the children of his first marriage to Elspeth –Andy, Aji, Gavin and Janie – were away from Scotland. After a few lonely years he and Ann got together in a partnership that lasted until his death.

David Harding, Ray Mckenzie & Alexander Moffat