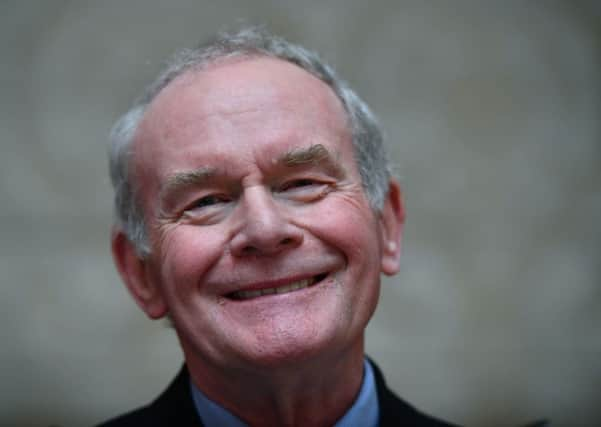

Martin McGuinness

Martin McGuinness was an IRA commander who became friends with his most implacable enemy.

His partnership at the top of Stormont’s power-sharing administration with fundamentalist unionist leader the Rev Ian Paisley would have been unthinkable in the days when republican bombs were ripping Northern Ireland and Great Britain’s cities to shreds and costing thousands of lives.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEx-first minister Dr Paisley was the Dr No who vowed to smash Sinn Fein but eventually said yes to sharing power with his foe in an often jovial partnership which saw them dubbed the Chuckle Brothers.

McGuinness was the extremist who once defended the slaughter of police and soldiers for a united Ireland but finally offered the hand of friendship to Britain. His partnership with the DUP leader as deputy first minister at Stormont was a shining example of peacemaking – of turning swords into plowshares.

McGuinness’ own version of Irish patriotism evolved from gunboat diplomacy to a ballot box struggle which was to see Sinn Fein become pre-eminent among nationalists and demolish a century-old unionist majority at Stormont after a party vote surge in 2017.

The Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday in 1972 said he “probably” carried a sub-machine gun during the massacre of 13 unarmed civil rights protesters by soldiers in Londonderry. He admitted to being second-in-command of the Provisionals that day.

The bluntly spoken young man was a ruthless proponent of republican violence, which caused more than half of the 3,600 killings between 1969 and 1998, in opposition to British rule in Northern Ireland but he became a senior member of Sinn Fein as the conflict neared its end. He was integral to nearly every major decision taken by the movement over the last 30 years, promising to lead it to a united Ireland. He did not succeed.

The former butcher from Derry, who took part in the street fighting of the 1970s and once defended the spilling of copious amounts of blood in pursuit of his political Shangri La, ended up toasting the Queen at Windsor Castle and shaking her hand in a remarkable gesture of reconciliation with Britain after a long career of peace-making.

McGuinness negotiated the 1998 Good Friday peace agreement, secured IRA arms decommissioning in 2005 and shared government with former enemies in Belfast as deputy first minister.

He felt the 2012 handshake with the Queen could help define “a new relationship between Britain and Ireland and between the Irish people themselves”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMcGuinness’s final significant act was to resign as deputy first minister and take first minister Arlene Foster with him, ending a decade of testy coalition government with the DUP.

McGuinness was born in 1950 in a terraced house in Londonderry’s Bogside housing estate, a one-time no-go area for soldiers and hotbed of IRA planning and activity.

He was educated at the local Christian Brothers school.

McGuinness showed little interest in politics before the start of the Troubles. He did not join the IRA until after the British Army had been sent to Northern Ireland in August 1969 to restore order after a pitched battle between the RUC and inhabitants of the Bogside. He was sufficiently highly regarded to be one of the IRA delegation flown to London to talk to Willie Whitelaw, the first-ever Northern Ireland secretary.

The republican was sentenced to six months in prison in the Republic of Ireland after being caught in a car containing large quantities of explosives and ammunition.

The teetotal, non-smoker with a love for Gaelic football, cricket and fishing insisted on “purity” from his fellow partisans in the IRA and when in jail in Dublin ordered his colleagues to remove pin-up pictures from their cell walls.

McGuinness said he left the IRA in 1974. Other accounts suggested he was made chief of staff of the organisation in 1978 and streamlined it into an urban guerrilla force based on small, tightly controlled cells.

Former Irish justice minister Michael McDowell said he was a member of its ruling Army Council. But his membership or otherwise of the IRA was irrelevant since he was regarded as having more influence than anyone over the men of violence.

He was instrumental in helping secure the IRA’s first cessation of violence in 1994, while in secret contact with the British, and later reflected: “In 1994, dialogue offered the only way out of perpetual conflict.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1997 he was elected Mid Ulster MP but did not take his seat as he would not swear an oath to the Queen.

As Sinn Fein’s chief negotiator of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement he helped establish the powersharing institutions and renounced violence.

In 1999 he became the chauffeur-driven education minister at the Assembly who was to scrap the transfer test at age 11, part of a power-sharing coalition of unionists and Irish nationalists at Stormont.

The DUP refused to work with him because of his chequered past. By 2005 the Provisionals decommissioned arms after McGuinness led negotiations – a process which started with the armed group vowing to volunteer not an ounce of explosives. By 2007 Sinn Fein had pledged support for the police force and Ian Paisley, the fiery preacher of “never”, was prepared as leader of the largest party to enter government with Sinn Fein.

The pair struck up an unlikely bonhomie heading the ministerial Executive. But it was not all laughs and in 2009 McGuinness described dissident republicans who murdered two soldiers and a police officer as “traitors to Ireland”.

When the Queen visited Dublin that year the veteran republican was absent but by June 2012 he was ready to meet her. They shook hands at a Belfast theatre and McGuinness said the encounter was “a result of decades of work constructing the Irish peace process”.

In 2014 he attended a banquet at Windsor Castle as part of a state visit by the Irish president and joined in a toast to the monarch. In 2013 he travelled to Warrington to speak at the invitation of Colin and Wendy Parry, whose son Tim was killed by an IRA bomb, to acknowledge their pain.

But he had more strained relationships with Mr Paisley’s successor as First Minister at Stormont, Peter Robinson, as the joint office was embroiled in controversy over property dealings. Difficulties also surfaced over welfare reform, investigating thousands of conflict deaths and a green energy scheme predicted to be £490 million overspent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter McGuinness gave first minister Arlene Foster an ultimatum to step aside, which was ignored, he resigned in January 2017. It was the last act of a career forged in the flames of Northern Ireland’s Troubles which reached its zenith after the guns had fallen silent.

He is survived by his wife Bernie and four children.

Michael McHugh and Chris Moncrieff