Lost Edinburgh: The Great Plague of 1645

Cases of bubonic plague were ferociously common in Europe throughout much of the Middle Ages before fading away around 300 years ago.

The epidemic later labelled the Black Death entered Italy in 1347 and spread quickly across the European continent. It was transmitted by the bite of infected fleas carried on the bodies of black rats. Those unfortunate enough to contract the virus faced almost certain death within just three to four days. During the 14th century the pandemic saw a third of the population of Europe and Asia perish.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe bubonic plague first ventured north of Hadrian’s Wall in 1349 – putting paid to the fallacious belief of many Scots at the time that it had been sent to the British Isles by the Almighty purely to punish the transgressions of the English.

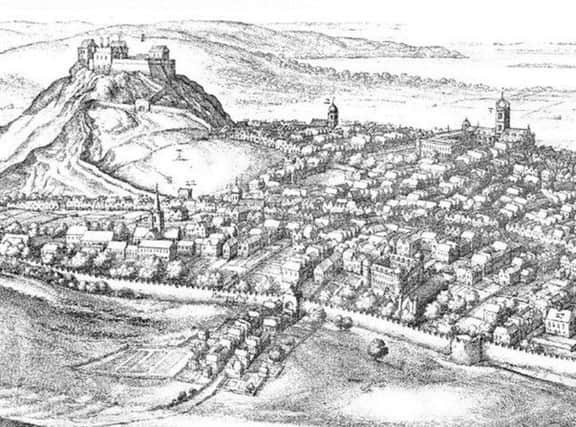

Edinburgh and its nearby port at Leith suffered intermittently from the plague over the next few centuries. The overcrowded and unsanitary, rat-infested conditions prevalent within the medieval city created the ideal environment for the lethal pathogen to thrive time and time again.

The Great Plague of Edinburgh

The plague epidemic which gripped Edinburgh in 1645 was, without exception, the most devastating that the city ever experienced. It is estimated that up to half of the population died, while in Leith the percentage was even higher - perhaps due to the steady influx of ships from all over Europe. Corpses littered the closes and local government collapsed as the infected fell in their tens of thousands.

Initial symptoms of the bubonic plague would appear very suddenly. Victims would begin to complain of a high fever after only a day or two, followed quickly by muscle cramps, gangrene and painful, swollen glands around the groin, neck and armpits. Once contracted, the disease was easily passed on and spread from host to host.

Those inflicted with the disease were either forbidden from leaving their homes or banished to quarantined huts outside the city walls in desperate attempts by the authorities to separate the healthy from the ill.

Plague doctors

In Edinburgh, as across Europe, a plague doctor visited contaminated properties on a daily basis. These new-age medics were distinctively dressed in long leather cloaks, large brimmed hats and grotesque beaked masks filled with sweet-smelling herbs. Doctors believed the herbs would repel the “evil smells” which were thought to carry the disease.

One of the plague doctor’s principal tasks was to pierce and drain the buboes – the pus-filled lymph nodes, of the victims before they ruptured independently and became septic. The wound would then be cauterised with a heated iron.

All in all it was an utterly unpleasant experience for the patient, who would more than likely die with or without treatment. Modern interpretations of the plague doctor’s mask can be seen today at the annual Carnival of Venice.

Burial pits

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo cope with the sheer number of dead bodies strewn across the city, massive burial pits were hastily dug at sites such as the Burgh Muir and Leith Links. The exact death toll was never recorded, but it is thought that close to 3,000 people died in Leith alone – roughly half of the port’s population. Edinburgh’s population around this time was approximately 35,000.

In 1647 the plague began to disappear from Edinburgh, never to return. The Great Plague of Marseille in 1720 proved to be the last significant bubonic plague outbreak in Europe. Scotland’s capital would not suffer from pestilence on such a scale again until the worldwide cholera epidemic of the 1830s.

Despite its 400 year absence from Edinburgh, the bubonic plague persists in other parts of the world, but advances in medicine since the days of leather-cloaked physicians with herb-filled masks ensure that the vast majority of those infected can now be effectively cured.

• Visit Lost Edinburgh on their Facebook page, and follow them on Twitter @lostedinburgh