Insight: Apply now if you want to live on Ulva – population five

It’s dusk and I am drifting through the eldritch rooms of the big house on Ulva like a character in a Shirley Jackson novel. Curtains billow around rickety windows, dusty books lie half-opened on library shelves and clean squares on stained wallpaper mark the spots where portraits once hung.

Though it’s eight months since the “laird” Jamie Howard left, and weeds have grown up through the balcony, the house has the feel of somewhere only just vacated. Three armchairs are gathered round a bay window seat, as if poised for conversation, and mugs lie upturned in the old kitchen sink.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUlva – off the north-west coast of Mull – is an island of ghosts. Ruins of old crofts, emptied in some of Scotland’s most brutal clearances, stud the land like teeth knocked out of a jaw. On the starkly named Starvation Point, a row of cottages serves as a monument to those who, too old and frail to make their way to the New World, died of malnutrition within their walls.

Almost as eerie are the more recent testaments to human productivity. There’s an abandoned farm, where black wool lies in a rotting heap; a workshop full of rusted tools, where a retired doctor once crafted objects out of wood; and six, still-furnished cottages, vacated one by one.

These remnants of a once thriving community give Ulva an air of melancholy. There are no roads and many bogs. But it is beautiful in its desolation. Land and sea thrum with wildlife – seals, otters, dolphins, hen harriers and sea and golden eagles – while from Ormaig, Iona, Staffa, Little Colonsay and the Dutchman’s Cap are clearly visible.

At its peak, Ulva was home to 859 and consisted of 16 townships, peopled by weavers, shoe-makers, tailors and blacksmiths. The clearances, carried out by the then owner Francis William Clark as the kelp industry foundered, saw the population shrink to 150 in the 1830s and 40s. A lack of investment by Howard, the third generation of his family to own the island, is blamed by many for its more recent decline.

Twenty years ago, there were still 30 people living on Ulva; today there are only five, split between two homes. In the Boat House, the island’s only cafe, which, in summer, serves up to 100 tourists a day, live Rebecca and Rhuri Munro and their children, Matilda, eight, and Ross, five.

Rhuri grew up on Ulva, Rebecca in Dumfries. They met on Mull where Rebecca spent her summer holidays. She had planned to go to university, but came up for one last summer and changed her mind. She and Rhuri took over the Boat House when she was just 19. They approached it with the audacity of youth and made a success of it against the odds.

In a small, run-down house, a mile away, down a dirt track, lives Barry George, a labourer from Newcastle, who came to the island to work on one of the fish farms. He now drives the Ulva Ferry Community Bus.

The two households regard each other warily. You don’t have to spend much time with one to hear criticism of the other. The Munros find Barry, who has 100 ideas-a-minute, “difficult”; he finds them clannish and exclusive. Yet they are united in their desire to breathe life back into Ulva; to banish its ghosts; see its houses filled, Highland cattle back in its fields and children running through its forests.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLast midsummer’s day, they celebrated as the North West Mull Community Woodland Company (NWMCWC) successfully purchased Ulva from Howard with a £4.4 million grant from the Scottish Land Fund. It was a long, arduous process achieved with little cooperation from the owner. Since then, they have been brainstorming ideas to reinvigorate the place.

With so much public money involved, there is a lot at stake, not just for the residents, but also for land reform champions and the Scottish Government, which invoked the Land Reform Act 2003 to take Ulva off the market.

Rhuri and Rebecca say their children love living in a place where they can run wild. “My favourite thing here is going for walks and looking for otters,” Matilda says. “We saw a mummy one and her two babies once.” She and her brother also play for hours on end in a tipped up wooden boat. “It’s not a den, it’s a spaceship. I am Gamora and Ross is Thor.” They are fans of Guardians Of The Galaxy.

“There is an innocence to growing up here,” Rebecca says,”but it would be nice for them to a have a few more friends to play with.”

Tucked away in his cottage, Barry keeps himself busy studying for an Open University degree and growing his own fruit and vegetables. He also advertises his property as a B&B, so he has company from time to time. But he misses the old social gatherings. “When I first moved here the houses were filled,” he says. “Every year, there would be a Burns Supper at the church. Iain Munro [Rhuri’s uncle and the farmer] would kill some sheep, and his wife Rhoda would make a big traditional haggis and clootie dumpling. There would be 60 of us sitting down to dinner and everyone got on. Someone would bring a fiddle or a squeeze box and there would be a ceilidh. Those were great nights.”

I have come to Ulva to find out how one goes about creating a new community almost from scratch. There have, of course, been other island buy-outs – Eigg in 1997 and Gigha in 2001 – and their populations have grown as a result, but they started from a bigger base (60 on Eigg and 98 on Gigha). Will families want to uproot and move to a place with three adults, no roads and no ferry after 5pm or on a Saturday? And if they do, how will the NWMCWC ensure they are the kind of people who are likely to stay the distance?

The first thing to point out is that Ulva is not exactly St Kilda. To get there from the mainland requires a 45-minute ferry journey from Oban to Craignure, a 40-minute car journey from Craignure to the tiny hamlet of Ulva Ferry and a two-minute boat journey across the Ulva Sound. Matilda and Ross travel backwards and forwards every day to the primary at Ulva Ferry. It currently has nine pupils.

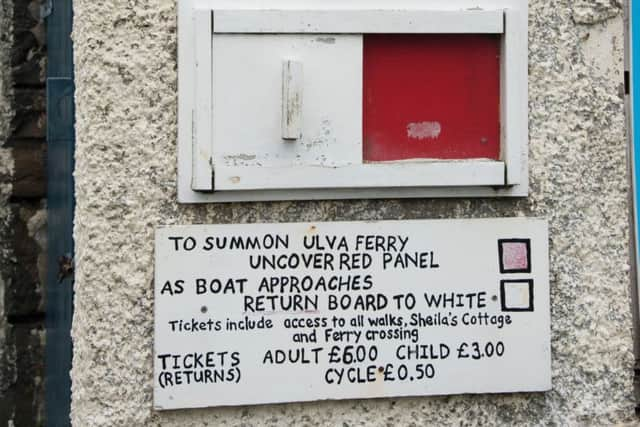

When photographer John Devlin and I reach the crossing point we discover the famous wooden signal board, traditionally used to summon the ferry, has been “borrowed” by the National Museum of Scotland for a land reform exhibition. Rebecca is in the process of making a new one, but until it is installed, her father-in-law Donald keeps his eyes peeled for passengers, then wheechs his empty sardine can of a vessel to the pier or the pontoon to pick them up.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDonald brought his wife and five of his children to Ulva (where his brother Iain and his family already lived) when he took on the role of ferryman 23 years ago; all except Rhuri have now moved to Mull and beyond. Iain and Rhoda moved to Gometra, a tidal island joined to Ulva by a bridge and a causeway after giving up the farm; and then Iain tragically drowned. Donald is not the most garrulous of seafarers, but standing at the rudder, with his trim beard and his trilby, he cuts a distinguished figure.

We disembark on the slipway in front of the Boat House, where the NWMCWC is holding one of its regular meetings. The first priority for the company has been the renovation of the crumbling quays on either side of the Sound, not only because islanders need to get back and forth, but because many fishermen, including Rhuri, land their catch on the Mull side.

By the time we arrive, work on the Mull pier has already been completed, but the Ulva slipway is bristling with activity. A digger is scooping up rubble, while men drill holes for metal bolts to join a fresh layer of concrete to the old one. Wooden planks are hammered together to make shutters for the concrete, which will be delivered by helicopter in two days’ time.

Inside the Boat House, the NWMCWC committee members are discussing another pressing concern: the fate of the six empty cottages. By the time the meeting is over, they will have signed off the refurbishment plans so applications for building warrants can be submitted. Once those properties are habitable, “suitable” tenants will have to be found.

To test demand, they asked the Highlands Small Communities Housing Trust to produce a survey for anyone interested in taking up residence. Five hundred people responded. The survey was very detailed, seeking information about expectations, skills and ability to work from home.

“Some of those who replied clearly thought we were St Kilda – that there would be no power – whereas, in reality, we are not really that remote. It’s only very rarely we can’t get across to Mull,” Rebecca says.

“We have 4G signal, we have broadband, we have Amazon deliveries, we have Netflix, so it would be possible to work from Ulva, but it would also be possible to live here and work on Mull.

“At the same time, anyone moving here would have to accept the limitations. The ferry only operates between certain times. You have to think ahead when you do your shopping. Yes, you can nip to Salen [on Mull], but it’s not like nipping to the end of the road. If you are moving here with high school kids, they are going to have to leave at 7.45am. For some people that might be too early. It’s about managing expectations.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPeople who have expressed an interest so far include artists, prospective guest house owners and a woman who wants to set up a pony-trekking centre.

So what kind of people are the community hoping to attract? “We haven’t finalised our allocation procedure, but we will be looking for a mix, because it’s a mix of housing,” says Rebecca. “We will want people who can contribute particular skills, but also people who are here for the long haul.” Anyone who wants to make the move will have to be unfazed by bad weather. “There’s a saying on Mull: ‘If you survive two winters, then you’re not going anywhere,’” Rebecca says.

The great thing about building a community from scratch is that you can think about the kind of environment you want to create. For example, the NWMCWC plans to rent out the refurbished houses so they remain in community hands. Later on, plots of land may be sold for self-builds. But if they are, there will be some kind of clause placing restrictions on resales.

Ulva currently has two Land Rovers (one of them left by Jamie Howard) and two quad bikes, but, in an effort to keep the 4,500 acre island unspoiled, the community will discourage newcomers from bringing more vehicles (much of Ulva is undriveable even by 4x4s ).

Another dilemma involves the deer population. At the time of the buy-out, there were an estimated 400 on Ulva; the number the island can sustain is between 70 and 80.

If the NWMCWC had decided to allow commercial shooting, they could have charged £2,000 a time, but, after some discussion, they agreed this was not compatible with their beliefs. Instead, they have brought in a professional marksman to carry out an annual cull, insisting on copper bullets rather than lead. The venison is processed at the community-owned abattoir on Mull and sold locally.

The fact the community has come so far so quickly is little short of a miracle. Unaware it was for sale until a photographer turned up to take pictures for the brochure, the NWMCWC had to make a “late application”. This meant it had to demonstrate a higher level of support than would normally be the case amongst local residents (there are 421 in its membership area) and draw up a series of detailed business plans in a short timescale.

Once it had been granted permission to proceed, it had to raise the cash. The Scottish Land Fund agreed to provide 95 per cent of the total. The rest came from the Macquarie Group, an Australian investment bank which takes its name from Lachlan Macquarie, a member of the Clan MacQuarrie which presided over Ulva for 800 years. Macquarie left Ulva, became governor of New South Wales and introduced Australia’s first currency, the holey dollar, which is the Macquarie Group’s logo. The NWMCWC had hoped for £100,000. The Macquarie group said: “How would you feel about half a million?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTaking control of the island, after centuries of powerlessness, has been thrilling and much has been accomplished. Rebecca has created new signs to direct tourists on the island’s many walks. Rhuri’s sister Emma, who helps run the Boat House, has cleaned the war memorial at the church.

But it is not without its challenges. One of the toughest was taking custody of and shearing Howard’s 50 Hebridean sheep. “The sheep haven’t been handled in several years, they have horns and are unpredictable,” Rebecca says, “so it wasn’t the easiest experience.”

The following day, after a night at Barry’s, NWMCWC director John Addy, Rhuri and Rebecca take us out to explore the island. Travelling in the Land Rover, we pass through a forest so green and mossy, it’s easy to imagine Gandalf in the distance. “Welcome to Middle Earth,” laughs John. The verdant landscape soon changes to starker woodland and then to moorland dense with bracken.

Rhuri drives us as far as he can; then we get out and walk for an hour and a half through driving winds to Ormaig and on to the stone bothy at Cragaig. On the way, we stop to watch a group of seals basking on a rock.

As we walk, our guides point out sites of interest. At Ormaig, they show us the house where Lachlan Macquarie was born. Macquarie turned Sydney from a shanty town to a Georgian city, but he was also the scourge of the indigenous population. “So we will have to be careful how we present him,” says John, his thoughts turning to the island guide they hope to produce.

With so much history, Ulva has much to offer tourists. The Vikings who invaded in the 9th century left a legacy of evocative Norse names. Ulva itself means Isle of Wolves; Ormaig means Bay of Serpents or Bay of Longships.

More tangible bounty comes in the form of the famous Brooch of Ulva discovered in a cave in 1998. What other treaures might the untamed land have to offer the avid detectorist?

The Brooch of Ulva, thought to date from the 16th or 17th century, is now in a museum in Dunoon. “Maybe, if we managed to turn the big house into a heritage centre, they would give us it back,” muses Rebecca. And that’s how the rest of the journey goes. One of the trio will point at a building or a field or a monument and talk about its potential. “If you come back in a year or so, there will be Highland cows here and more trees there,” they say. “The church will be reopened, the big house will be restored to its former glory, there will be new routes for walkers and more places for tourists to stay the night.” They also hope to reopen the oyster farm and turn the old shooting lodge into a bunk house and camp site.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTheir excitement is so contagious, and their vision so vivid, it transforms the landscape from blustery grey to technicolour; like Kansas yielding to Munchkinland.

Inevitably, given its importance, politicians are keen to keep the Ulva community buy-out in the public eye. Suspicions the SNP were trading on it were heightened when Nicola Sturgeon chose to announce that permission to proceed had been granted at the 2017 party conference. Later this month, John and Rebecca are heading to Westminster where Argyll and Bute MP Brendan O’Hara is hosting a reception.

The NWMCWC is also hoping to mark the first anniversary of its ownership with a low-key music festival in the grounds of the big house. There is certainly much to celebrate: in the short period since the deal was sealed, the islanders have proved they have ideas and energy aplenty.

The buy-out seems to have galvanised the wider community too. Residents of North West Mull do see Ulva as an asset; last month, a group of volunteers took part in a beach clean, collecting seven large bags of rubbish washed in on the tide.

But there is a long way to go and many hurdles to overcome before it can be declared a success. Even with their newly-appointed development manager Ben Sunderland there is a lot of work to be done by a handful of people. Rebecca points out the pressure will ease as more families move in and the work is shared, but in the summer she and Rhuri will have to devote most of their time to running their cafe and looking after their children.

The project poses some philosophical questions too: to what extent is it desirable, or even possible, to socially engineer a community? “We don’t want the wrong kind of people,” Barry says. But how do you judge the “right” kind of people? Whatever allocation policy the MWMCWC comes up with will be an attempt to guarantee a harmonious environment. But aren’t human relationships too complex to be managed by algorithms?

The friction between Barry and the Munros shows how difficult it can be to see eye to eye in even the tiniest communities. What happens when more families move in and want their opinions taken into account? Tales of in-fighting and debt have long been filtering out of Gigha.

The NWMCWC is determined to surmount these obstacles; the residents of Ulva, in particular, have the motivation to make it work because they have invested so much sweat and tears in the island. You only have to watch Barry’s face as he talks about the first time he saw his cottage to understand that he is bound to Ulva by the kind of hard-won love that withstands adversity. “It was a glorious red hot sunny day and I was blown away,” he says. “The cottage was full of rat holes and when I opened the window the bottom part stayed put and the glass came down like a guillotine, but I patched it up as best I could and thought, ‘I’ll have this’.” Barry shows us photographs taken when the moon is full and Orion’s Belt is clear in the night sky.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt present, when the ferry stops for the evening, the five remaining residents have Ulva to themselves. Surely they must be ambivalent about sharing their little bit of paradise with other people. “It is magical,” Rebecca concedes.

But enforced solitude can take its toll. “One weekend, some years ago, everyone on the island, was away at the same time so I went up to the summit [of Beinn Eoligarry],” Barry says. “I stood on the top and thought: ‘I am here all alone. This is my island.’ I came down and by Saturday teatime people had started to come back.

“Just before Christmas, Rebecca and Rhuri were away somewhere and I went up to the summit again, but it wasn’t the same. This time I was alone because so few people live here. I am alone because I am alone. I hope the buy-out will change all that.”