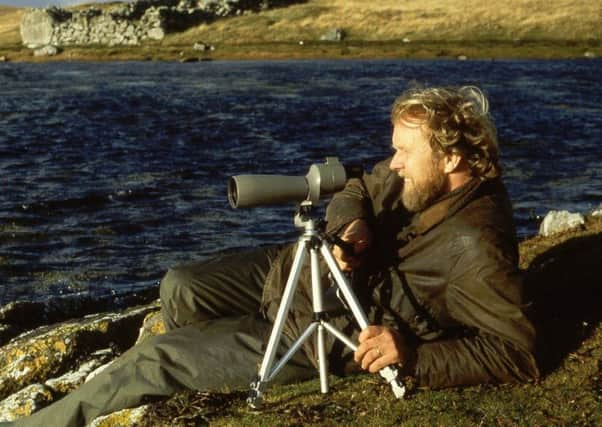

Hans Kruuk: The fight for survival is brutal and captivating

I still see that endless, dusty, gravelled track from the African, Tanzania town of Arusha into the Serengeti, as it winds its way down from the rim of the Ngorongoro Crater, down from the clouds over forested heights, down from the trees with their curtains of lichens hanging almost across the track. Once out of the cloud forests, dust takes over, and the spectacular views over the plains of the high plateau make it difficult to keep my eyes on the treacherous dirt road, while driving my Land Rover.

My first sights of wild African animals, many years ago, stay deeply engrained on my mind. I am staggered seeing those giraffes and elegant impala, just outside the outskirts of Arusha, the elephants and buffalo on the road along the rim of the Ngorongoro Crater. Then comes the Serengeti itself, across the famous Olduvai Gorge, with wildebeest and zebra, endless herds of them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA spotted hyena, my first, lies in a small muddy puddle next to the track, on our way to the Serengeti headquarters in Seronera. A good-looking female, she wallows in the cool mud, and Jane and I cheer it. I think it is then and there that I decide to really concentrate my study on that animal, on that species, in favour of all the other carnivores there. Serengeti has more than 25 species of them, but I realise that studying every single one would have meant drowning in diversity. I meet the famed Serengeti lions and other large cats, but I am taken by the underdog, the much-maligned spotted hyena, which is also the most numerous large carnivorous animal here.

Now, years later, I know that a hyena, reviled as it is, can make a wonderful warm companion. Our Solomon lived with us in our Serengeti house, tame but also wild, away for days on end but bursting into the house again to share my bath, hilarious and full of mischief, stories of which I share in my book. His wild mates, as I found for the first time, live in clans, fascinating communities of sometimes 80 hyenas or more. Their females are the dominants, they are the warriors, the Amazons, they lead in the hunts. I still find nothing more exciting than driving alongside a pack of hyenas, hunting zebras, or a single hunter chasing and pulling down a wildebeest, or a mob attacking a rhinoceros. For me, the most thrilling sounds out there are the distant ‘whoo-oop’ calls of the hyenas, and their unbelievably varied repertoire of sounds.

Unbeknownst to many, hyenas of the Serengeti are predators, they are the wolves of the savannah. Many a time hyenas kill at night, then are chased away by lions, and dawn finds the hyenas waiting for the scavengers to go away again. People interpret this classical picture of lion and hyena, but wrongly.

Living in the Serengeti I am surrounded by wild animals, where roaring lions keep us awake at night, where buffalo scrape themselves against the house, where a peeing giraffe sounds like a burst drain-pipe, where a pair of shoes left on the veranda is quickly eaten by the wild hyenas. From the house, we hear hyena clans indulging in dramatic battles, involving large numbers of individuals, almost complete armies with a cacophony of sound. The organisation of these animals is unusual at every turn, and perhaps especially interesting when so often one is reminded of mankind’s own affairs. I discover the problems that hyenas cause the Masai people, and human hair in hyena faeces may explain their role in witchcraft. In the deserts of northern Kenya I see where they kill livestock and endanger the tribal people.

Later, quite different research leads me to Galapagos, where wild, feral dogs attack the large, imposing iguana lizards, which I watch in detail so I can advise the management on how to handle this problem. Then I walk in English and Scottish woodlands at night following badgers, to discover the badger clans and how they are organised, their wonderful system of communicating, despite their rather boring diet of earthworms.

Through watching badgers on the magnificent coastal slopes of western Scotland I come across otters, another carnivore in trouble. They bring me to Shetland, where they are easy to watch along the beautiful, lonely coasts. I study what makes these animal tick, why there aren’t any more than what we see, I snorkel with them. Watching otters also presents deeply emotional problems – what to do when, repeatedly, I see otter mothers abandon cubs and let them drown. Do I interfere, or let nature take its course? In my book I try to describe what I did, but when thinking about it I am still unhappy. Despite such apparent carelessness or cruelty, otter mothers in Shetland carefully select the larger fish from what they catch, to take to their waiting cubs. Looking after cubs is hard work and for mothers only. Not surprisingly, otter life is usually only short.

Otters come into my Scottish garden, attracted by the many frogs and toads in the pond. They are the same animals I can follow by using small radio-transmitters, as they cruise the river and the local lochs. It is mostly the males that use the river, the females staying on the lochs, making huge covered nests in the reed beds. I see the males diving when they spot a salmon-fisher, passing unnoticed under his fishing line.

Watching otters in Thailand, along a wide, sandy river where there are three different otter species, I meet monks, sitting quietly along the same, beautifully forested and sandy river banks, where a tiger takes a sambar deer whilst I try to sort out how three different otter species can subsist in the same places (answer: by eating different prey).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSpending time with any of these animals, watching them in their natural habitats, helps to appreciate their problems, and to understand what limits their numbers. I hope that many others will discover the natural history that I pursue, to help the world sort out its life with wild animals here, and everywhere.

The Call of Carnivores, Travels of a Wildlife Ecologist by Hans Kruuk is out now, in paperback, Pelagic Publishing, £19.99.