Whales Scotland: Why are we seeing whales washed up on Scottish shores?

Increased sightings of the distinctive dorsal fin and the sound of flukes slapping the surface in Scottish waters is testament to the more active migration route of these lumbering mammals.

Experts say there are still low densities of the species in Scotland’s seas, which they migrate through between their breeding grounds off Africa to their feeding grounds around Iceland and Norway. But an increase in opportunistic observations suggest numbers are growing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

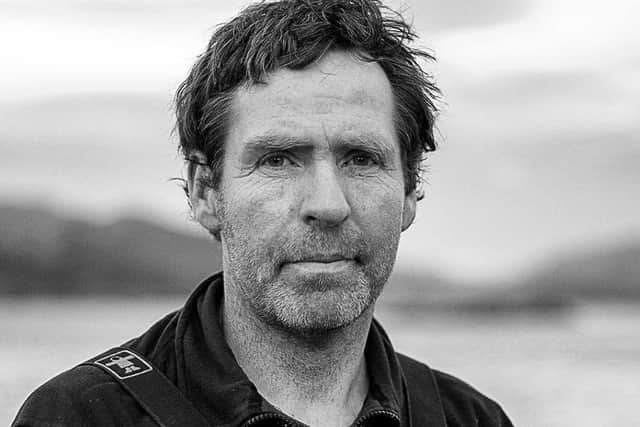

Hide AdEarlier this month, NatureScot manager David Steel caught site of a humpback off the Isle of May, about 30 miles from Edinburgh, where he documents wildlife.

“I have been here for nine years and I’ve seen three in the last four years,” he said. "There has been a noticeable increase in sightings on previous decades.”

The clampdown on hunting whales is said to be one of the reasons for the “overspill” of humpbacks to the UK’s coastline.

Dr Kevin Robinson, director of the Cetacean Research & Rescue Unit, also cited warmer seas as a reason and “the rich productive waters to the north and north-west of Scotland, which provide a suitable habitat for the magnificent whales which we expect to encounter more and more of.”

Entanglement

There are about 135,000 humpback whales globally, according to NatureScot. A report in the Nature journal said the population plummeted to 1,400, or even lower, in the 1960s.

But as the mammal makes a slow recovery, an increase in human activity at sea has presented the species with a new problem – entanglement.

Earlier this month, a juvenile female humpback was found washed up on the banks of Loch Fleet, which is about 45 miles north of Inverness on the Sutherland coast.

The Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme (SMASS), which performs autopsies on marine animals, found “clear evidence of acute entanglement”. The whale also had older abrasions from previously being caught in netting.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSMASS director Dr Andrew Brownlow said these injuries were common in larger, washed-up marine life, and there had been a “clear increase in the number of entanglement cases”.

He said the whale would have likely become trapped in netting, struggled to break free and drowned before washing up on land. Although SMASS said it could not be 100 per cent sure about the origin of the rope, the pattern would be “highly consistent with creel rope”.

Creel fishing

A report released in December found “considerably more whale entanglements occur in the Scottish creel fishery than previously thought”.

The study, which included authors from the University of Glasgow, said estimates of six humpback whales and 30 minke whales – the latter being the most common species of the baleen whale seen off Scotland – become entangled each year.

Where entanglement was reported, 83 per cent of minke and 50 per cent of humpback whales were caught in groundlines between creels.

Two minke whales have washed up on the North Berwick coast in the last month, with East Lothian Council saying it now expects about three or four dead whales a year in the area.

95% of entanglement cases go unreported

Mr Brownlow said while entanglements specific to humpbacks were rare off Scotland, with about 20 being reported in the past decade, alarmingly 95 per cent of entanglement cases involving large marine animals were likely to go unreported. This can be due to underreporting and logistical challenges in recovering at-sea carcasses.

Among the cases that are reported to SMASS, he said the main cause of death has been entanglement. “These animals are swimming through a forest of rope,” Mr Brownlow said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The number of fishing equipment in our waters has increased massively, so there is a major problem with the material out there.”

A population projection in a recent study found the humpbacks were not recovering as fast as expected. Mr Brownlow added: “There is an urgent need to understand how creel fishing can be mitigated and we urgently need the Scottish Government to help fund us for this.”

Action being taken

SMASS and researchers have said there has been a positive, active engagement from Scottish creel fishermen to tackle entanglement cases.

The Scottish Creel Fisherman's Federation (SCFF) is part of six groups that make up the Scottish Entanglement Alliance (SEA), which launched in 2018, and has spent the last few years trying to better understand the scale and nature of the problem.

SEA has recently started a “sinking ground-lines” trial, funded by NatureScot, which involves swapping out buoyant ropes used in creel fisheries for lead ropes that sink to the seabed, which are said to pose less risk to marine life swimming by.

Bally Philp, a creel fisherman based on the isle of Skye, and who is a representative of SCFF, said the trial was weighing up the practicalities, safety and financial costs involved in the potential transition.

“Hopefully it goes without saying there's no creel fisherman who wants to entangle a whale,” he said. "We are doing everything we can to reduce and ultimately eliminate entanglement as an issue in our fisheries.”

Ellie MacLennan, who has been coordinating the SEA project and who is studying a PhD in entanglement mitigation at the University of Glasgow, said creelers had been “really pro-active” in addressing the issue.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It’s important that the project is very much industry-led and involves the fisherman,” she said. "There is plenty of enthusiasm from creelers, but we need to keep up the momentum and start expanding this work to other fishing sectors.” She said the sticking point for progress is funding.

Funding for the first phase of the SEA’s project, which looked at the scale of the issue in Scotland, came from the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund, which the project is no longer eligible for following post Brexit.

For the second phase, which looks at exploring mitigating factors, Ms MacLennan said the project had been unsuccessful in obtaining sufficient funding, despite SEA submitting several applications.

In response, the Scottish Government said it was using its Nature Restoration Fund to support research trials into sinking groundlines in Scottish creel fisheries and pointed to its “Our Fisheries Management Strategy”, which sets out how to address bycatch and entanglement.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.