Some Antarctic ice shelves grew in area over the last 20 years – study

Researchers say that sea ice, pushed against the ice shelves by a change in regional wind patterns, may have helped to protect the ice shelves from losses.

Ice shelves are floating sections of ice attached to land-based ice sheets and they help guard against the uncontrolled release of inland ice into the ocean.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the late 20th century, high levels of warming in the eastern Antarctic Peninsula led to the collapse of the Larsen A and B ice shelves in 1995 and 2002 respectively.

These events drove the acceleration of ice towards the ocean, ultimately accelerating the Antarctic Peninsula’s contribution to sea level rise.

There was then a period when some ice shelves grew in area, but since 2020 there has been an increase in the number of icebergs breaking away from the eastern Antarctic Peninsula.

Academics, who used a combination of historical satellite measurements, along with ocean and atmosphere records, said their observations “highlight the complexity and often-overlooked importance of sea ice variability to the health of the Antarctic Ice Sheet”.

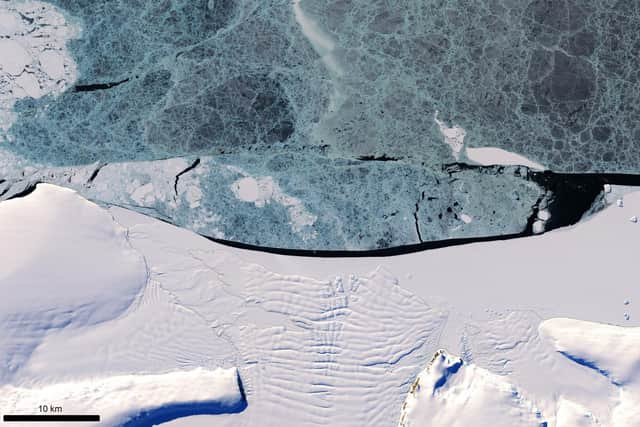

The team of researchers from Cambridge University, Newcastle University, and New Zealand’s University of Canterbury found that 85% of the 1,400km-long (870 miles) ice shelf along the eastern Antarctic Peninsula “underwent uninterrupted advance” between surveys of the coastline in 2003-4 and 2019.

This was in contrast to the extensive retreat of the previous two decades.

Research, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, suggests the growth was linked to changes in atmospheric circulation, which led to more sea ice being carried to the coast by wind.

Dr Frazer Christie, from Cambridge’s Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) and the paper’s lead author, said: “We’ve found that sea ice change can either safeguard from, or set in motion, the calving of icebergs from large Antarctic ice shelves.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Regardless of how the sea ice around Antarctica changes in a warming climate, our observations highlight the often-overlooked importance of sea ice variability to the health of the Antarctic Ice Sheet.”

In 2019, Dr Christie and his co-authors were part of an expedition to study ice conditions in the Weddell Sea offshore of the eastern Antarctic Peninsula.

Expedition chief scientist and study co-author Professor Julian Dowdeswell, also from the SPRI, said that during the expedition it was noted that parts of the ice-shelf coastline were at their “most advanced position since satellite records began in the early 1960s”.

Following the expedition, the team used satellite images going back 60 years to investigate in detail the temporal pattern of ice-shelf change.

Currently, the jury is out on exactly how sea ice around Antarctica will evolve in response to climate change, and therefore influence sea level rise, with some models forecasting wholescale sea ice loss in the Southern Ocean, while others predict sea ice gain.

But icebergs breaking away in 2020 could signal the start of a change in atmospheric patterns and a return to losses, according to the research.

Dr Wolfgang Rack, from the University of Canterbury and one of the paper’s co-authors, said: “It’s entirely possible we could be seeing a transition back to atmospheric patterns similar to those observed during the 1990s that encouraged sea ice loss and, ultimately, more ice-shelf calving.”