Sea eagle impact goes beyond lamb predation as farmers share concerns over finances and mental health

Every year during the lambing season, one of Scotland’s reintroduced apex predators dominates conversations on west coast farmland.

Once extinct in the UK, the white- tailed eagle, otherwise known as the sea eagle, has been thriving in the Highlands and Islands since it was brought back in the 1970s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith a wingspan reaching up to 8ft, the species is Britain’s largest bird of prey and has been known to feast on lambs.

The impact of the bird’s evolved diet has forced the Scottish Government agency NatureScot to set up schemes to protect flocks from the burgeoning eagle population.

But the consequences of such a reintroduction goes far beyond the distress caused by a lamb being plucked from a ewe’s side, said Jenny Love, a sheep farmer near Oban.

“There is a misconception that these birds only impact lambs,” she said. "That’s not the case; it’s the whole flock, and of course the farmer.”

A consultant at the Scottish Agricultural College, Ms Love is in regular contact with livestock owners in the area.

She said the plucking of lambs is reducing the quality of farmers’ flocks which many take immense pride in.

“Farmers want their herds to be healthy, it’s why they get out and do what they do,” she said.

"A lot of the sheep are hefted to the hill, so when you lose lambs because of the eagles, it’s not as easy as some might think to build numbers back up.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHefting means farmers do not need to fence sheep in because they “know their hill”, said Ms Love; an instinct the hardy animals pass down through generations.

“If you try and up your numbers to mitigate the eagle issue by buying new sheep, it ruins the quality of the stock because they aren’t bread from the same flock.

“The new ones just don’t do well in the environment; and some just die.”

Farmers mental health

But the knock on effect doesn’t stop there.

Recent figures from the Royal Society of Edinburgh found that the cost of living crisis, Covid-19 and the effect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has had more of a significant impact on rural areas across in Scotland than on urban areas.

The report highlighted prices in remote rural communities for some essential goods were already higher than those in urban centres, and recent increases in inflation has made living cost pressures worse.

Ms Love said the damage caused by sea eagles is only perpetuating what is already a financial and mental health crisis in the farming community.

She said one farmer in Argyll, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of backlash from some wildlife campaigners, said they were losing well over £10,000 a year because of sea eagles preying on lambs.

“There is just a lot of sadness about what to do next because there’s no clear help,” she added.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"It’s really concerning for livelihoods here. There is a high suicide rate in the farming community; we need to take more care.”

Office of National Statistics revealed last year that 133 people in UK farming and associated agricultural trades took their own lives in 2019-20; with 31 of them in Scotland.

A survey carried out by the Farm Safety Foundation in 2022 also found that 88% of farmers under 40 rank poor mental health as the biggest hidden problem facing the industry.

And, earlier this year, chief executive of the Royal Scottish Agricultural Benevolent Institution (RSABI) Carol McLaren said demand for counselling services has trebled over the past year citing uncertainty over future financial support for the industry.

"There needs to be a structured, case by case approach to helping those who are affected, with tier level funding depending on how bad the damage is from these birds,” Ms Love added.

"Farmers don’t want to shoot the birds, but at what point is control going to be put in? They’ve gone an introduced an apex predator, but with no plan.”

What schemes are in place?

Currently, farmers are supported by a NatureSoct Sea Eagle Management Scheme (SEMS), for which the standard measures are capped at £1,500 to mitigate damage caused by sea eagles, the same as in 2011.

David Colthart, chairman of the Argyll and Lochaber Sea Eagle stakeholders group, who is a Nature Scot monitor of the birds, and who farms 3,200 acres in North Argyll, said the funding is “way below what is should be”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"It’s a fraction of what it should be given the impact up and down the west coast.”

To bring the scheme into perspective, the RSPB claimed last year that the economic benefit of these birds to Mull alone was up to £8m annually; and there are 22 breeding pairs on the island.

Mr Colthart, who is also one of NFU Scotland’s representatives, said the annual spend for nearly 190 SEMS participants was £266,000 in total. It means the total funding for the whole of Scotland for sea eagle management is less than the supposed economic benefit of one nesting pair on Mull.

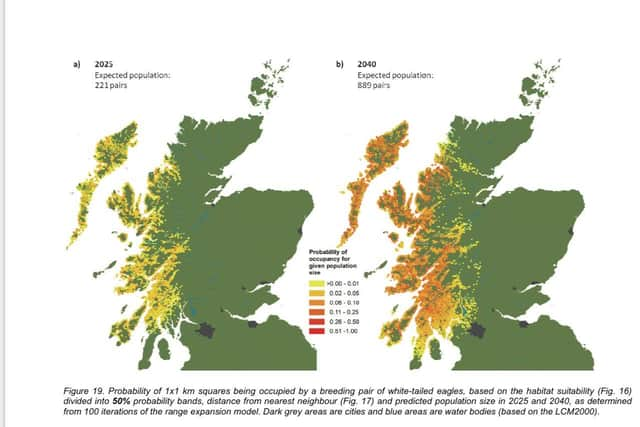

But what is even more worrying, he said, is the lack of a budget plan ahead. Local farmers on the ground have said the sea eagle population is on track to mirror the 2016 forecast by NatureScot which said there could be 225 pairs by 2025. There are currently about 150, according to RSPB.

"With limited alternative prey for these birds and lambs being an easy target, the issues will only get worse,” Mr Colthart added.

"The scaring and diversionary feeding techniques currently used by NatureScot to deter the birds aren’t sufficient in some areas, and NatureScot knows this.

Duncan Orr-Ewing, head of species and land management at RSPB Scotland said while he is aware incidents happen, he said “a relatively small number of farmers and crofters are impacted” by the sea eagles.

He insisted “most sea eagle pairs have an entirely natural diet” comprising of seabirds, fish and geese.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn response, Mr Colthart said farmers are concerned some conservationists involved in the sea eagle reintroduction initiative do not believe the reality of the impact farmers and crofters face on the ground which perpetuates an “us and them” dynamic.

NatureScot said it recognises that white-tailed eagles “can cause economic impacts to farms and crofts in some locations.”

A spokesperson added: “We are committed to continuing to run the SEMS beyond the current scheme end in December 2023.

"While budget constraints mean there may be some changes to the detail of the scheme, the intention is to provide continued support to farmers and crofters, especially for those suffering the greatest impacts.”

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.