'Not a problem, but an opportunity': The push to reclaim Scotland’s abandoned land

When Glasgow charity Maryhill Integration Network (MIN) first inherited the old school building where they base their activities, the group largely ignored the derelict space adjacent to the building, which was strewn with rubbish and overrun by waist-high weeds.

The charity, says MIN development co-ordinator Rose Filippi, didn’t have the “time or resources” to utilise the courtyard until 2013, when they received funding from “Stalled Spaces”; a council-led initiative to put disused spaces back into the hands of local communities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the next few months, the space was transformed – refugees, locals and even toddlers with plastic spades got stuck in, plucking out weeds, building planters, and eventually, seeding vegetables and flowers which bloomed in the newly-named Many Hands Community Garden.

The garden spawned far more than flowers, creating community gardening groups, cookery evenings and “building friendships across languages and cultures”, says Ms Filippi, who explains that interest in the garden further led to MIN’s involvement in tree-planting schemes elsewhere in Scotland:

“[For refugees] the tree planting was incredible – they not only created a new forest, but they also – literally – put down roots in their new country,” she said.

It is proof better than any that, in the right hands, derelict land can go from being a literal barrier in a community to an asset that brings its residents together. Yet in Scotland today, vacant sites remain a stubborn, far-reaching issue.

From tiny plots like the one Many Hands was built on right up to vast, sprawling estates, Scotland is home to around 11,000 hectares of vacant and derelict land, with just under a third of the population living within 500m of a site.

A visible legacy of Scotland’s industrial history, vacant and derelict land (VDL) is largely concentrated in urban areas like Glasgow, creating problems that run much deeper than simple aesthetics.

Though stressing there is “little research in the area”, Sebastien Chastin, professor of health dynamics at Glasgow Caledonian University and co-author of a 2019 report into VDL, says there is evidence to suggest such sites have an “impact on health, mostly around premature mortality”.

More solid data based on Glasgow residents, he says, has shown people living near VDL “perceive their health as being poorer” as well as having lower perceived mental health compared to the wider population.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome sites are polluted, while others create access problems for the less mobile.

VDL has impacts on crime, anti-social behaviour and people’s perceptions of an area, creating what Prof Chastin refers to as a “chicken-and-egg” situation in less affluent communities, which are home to the highest concentrations of VDL.

“It becomes a self fulfilling prophecy”, explains Shona Glenn, head of policy and research at the Scottish Land Commission.

“People have left the area, meaning it’s not attractive for businesses, it doesn’t have high land values and isn’t very attractive for development, so the private sector doesn’t really want to go there.”

Over several years, this process creates a cycle of decline, leading to long-term abandonment of sites, or worse, more VDL being created.

It is a situation that’s “not really been changing at much pace”, says Ms Glenn, who explains that a tendency to “write off” VDL as “too difficult” to take on is partly to account for the slow pace of change.

“It’s important to see these sites not as a problem, but an opportunity for Scotland,” she said.

“When you look at any area of public policy at the moment which is a government priority, this land could help – growing food, building social housing, creating green spaces, improving biodiversity.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScotland, says Prof Chastin, is “very forward thinking” when it comes to VDL, with the Land Commission last year presenting the government with a host of recommendations for tackling the issue and putting VDL to better use.

Given the sites are empty, the solution might seem glaringly obvious – free up the land and hand it over to interested parties to build social housing, parks or gardens.

In practice, however, things are much more complex. Some sites have extremely complicated ownership structures, while others lay waiting for promised development that never comes.

Some are physically contaminated, while others are totally unsuitable for building on.

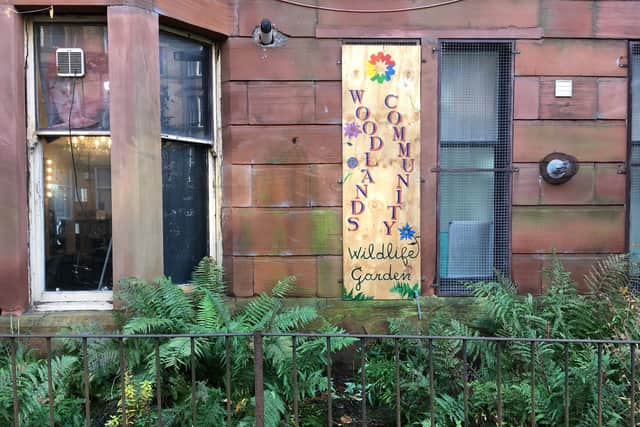

Tim Cowen, manager at Glasgow’s Woodlands Community Trust, describes the trust’s process of leasing a long-vacant site from the council as “painfully slow” and expensive.

“There were legal complications, issues to do with disputed titles … we had legal bills of about £10,000 to get the lease,” he says.

It is a tricky and drawn-out process also familiar to Rob Morrison, from community interest company Agile City.

Based in Speirs Locks, north Glasgow, an area with high levels of VDL, Agile City consults with local partners and the community to ascertain how sites should be repurposed to best serve the needs of the community.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile “ideas-making” is a relatively easy and exciting part of the process, says Mr Morrison, putting those ideas into practice is less straightforward, involving “different permissions, different types of funding and lots of complexity”.

The gap between the inception of an idea and it becoming a reality, says Mr Morrison, not only leaves sites vacant for longer, but can also lead to “consultation fatigue” as local people become tired of discussing regeneration without ever seeing real change.

Mr Morrison says temporary solutions can help to alleviate the issue, with Agile City themselves setting up “meanwhile uses” on vacant sites.

“We set up some really basic infrastructure like containers and deliver a programme of events and activities that invites people to participate in things they might want to see like cycling workshops, growing initiatives,” he says.

Temporary uses also have the advantage of “allowing you to see whether there’s a need for something in the community”, says Mr Morrison, meaning the eventual permanent solution is shaped by the demonstrable needs and wants of people who live near the site.

Community groups like Agile City, says Ms Glenn, “certainly have an important role to play” when it comes to transforming VDL, but they can’t be the whole solution – with some sites better suited to large-scale development like housing.

The potential for VDL to solve some of Scotland’s biggest challenges – from the environment to homelessness – is “exciting”, Ms Glenn says. But as it stands, she says more needs to be done around registering sites, funding regeneration and disincentivising owners from sitting on assets or abandoning land altogether.

This latter issue will become especially pertinent in coming months and years, with the folding of high street businesses potentially creating hundreds more disused sites.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It’s a huge risk”, explains Ms Glenn. “Our current legacy [of VDL] was caused by a major structural shift in the economy – what we’re looking at now is another major structural shift and there’s a risk that the same thing will happen again unless we take action”.

Mr Cowen, like many other third-sector workers, would advocate for occupying empty shops with “local enterprises, food initiatives, pop-up arts” and other ventures to serve local communities, but fears the reality could be losing out to commercial interests.

“We’ve looked at shop premises for ourselves in the past and the cost is just prohibitive,” he says. “When you’re competing with a commercial housing provider who’s going to build luxury flats and make lots of money, that’s the challenge.”

Post-pandemic, says Mr Morrison, VDL presents an exciting opportunity for communities to have a say in what structures or initiatives the sites should be used for.

“The pandemic has made people feel more connected to the places that they live in, whether that’s a sense of community on their street or generally feeling connected to a neighbourhood,” he says.

Using VDL to serve local needs, he adds, isn’t just about catering to demand – it also allows people to feel a sense of ownership over the place in which they live.

“Because of particular ownership structures within cities, people can feel like everything’s very divided up in terms of what’s yours and what’s not yours,” he says.

“Having opportunities to actually create, and literally build something in public space, it’s very rewarding. People feel much more affinity to a space when they’ve helped to create it.”