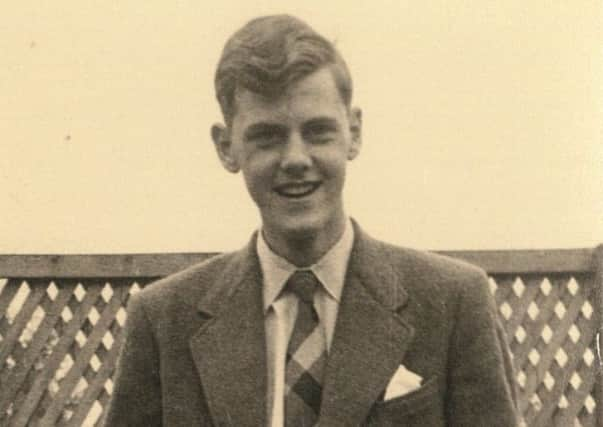

Appreciation: Roderick Graham

Expansive in his friendships, and inspiring loyalty in others, he was authoritative in demeanour, flamboyant in dress, a riveting raconteur with features that could switch in a flicker from impish wickedness to those of a cherubic small boy. And latterly, in the face of adversity, preserving a strength of spirit, and good humour, that could be humbling. Recently he even acquired a new skill: steering his motorised buggy, without mowing down the music-lovers outside the Queen’s Hall.

Edinburgh-born, and educated at the Royal High School and the University of Edinburgh, Roderick served as staff officer with the Royal Army Education Corps, at the East Africa Command, in Nairobi. Much of his time was devoted to an amateur drama company, and to Forces broadcasting. One proud boast: that he got to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro with some equally unathletic friends, their essential equipment being 200 Players cigarettes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn leaving the Army he moved to London where he embarked on a career as a writer, freelance director and producer.

Joining the BBC, and after a spell with External Services, he entered television drama, which was enjoying a golden age. Starting out as a PA on the televised version of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Wars of the Roses, his first directing job was The Canterbury Tales with Michael Bakewell, Head of Plays, whose earliest memory of him was of looking in on a production Roderick was working on. He was standing in the middle of the set, Bakewell recalls, on the edge of a forest with a blizzard whirling round him and completely covered in fake snow. “There’s something not quite right,” came the voice of the director from somewhere behind the camera. “What exactly did you have in mind?” Roderick replied with barely concealed irony. Here is a man, Bakewell thought, I’d like to get to know. Trying not to laugh, he went on his way, but “it was one of those defining moments in life and marked the start of what would become a close and enduring friendship that spanned half a century. “Over the years,” he says, “they worked together, travelled together, laughed together and, among other things, cracked open many a bottle of champagne together, never tiring of each other’s company. He was the best of companions, the best of friends: life will be much the emptier without him.”

Among Roderick’s credits was the genre-changing police series Z Cars; while Elizabeth R, starring Glenda Jackson, won four Primetime Emmys. He enjoyed relating how, having collected his, in person, at the Hollywood awards ceremony, he received a surprise cable from David Attenborough (then Director of Programmes) telling him to take a couple of weeks off, but to make sure and keep all his receipts and ticket-stubs.

Kenneth Dunn, Head of Manuscripts at the National Library of Scotland, after saying how engaged, and engaging – and what fun – he found Roderick, stressed that “most of all, I valued his dramatic knowhow and historical scholarship which combined in that famous 1971 production of Elizabeth R, a key point in my becoming immersed in history, even as a boy. I shall always be grateful for that, and I delighted in adulthood in developing a friendship with that learned producer.”’

During that period Roderick also took pride in the Sextet – a group of actors, among them Denholm Elliot, Billy Whitelaw and Dennis Waterman, performing plays by Hugh Whitemore, Dennis Potter and others.

It’s said playwright David Hare, who thought Roderick “such a fine producer and excellent director”, on hearing that he also wrote, could only exclaim, “He writes, Heaven help us!”

In 1977, Roderick moved to Glasgow to become BBC Scotland’s first Head of Television Drama. Amid devolutionary fervour and media clamour, his output ranged from Boswell for the Defence, Sutherland’s Law and Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s Scots Quair trilogyto commissioning Bill Forsyth to adapt and direct George Mackay Brown’s Andrina, filmed in Orkney and winner of the Grand Prix at the Celtic Film Festival.

He also mounted a Scottish Playbill series. There were original works by Jack Ronder, Tom Wright and Eddie Boyd.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne established writer, Joan Lingard, found Roderick “a sympathetic listener, always good to talk new ideas with, encouraging her to feel they would develop; genuinely and intelligently interested in what was going on, and in other people’s work, but without interfering; and a keen facilitator” – not least in enabling two series based on her Maggie books, shot with the aid of BBC Scotland, to attract a national UK audience.

It was around then I first encountered Roderick: his riposte on hearing I worked in radio, was: “Ah, that’s where an actor says, ‘This gun I’m pointing at you with my right hand is loaded’. As well as sensing his sense of the ridiculous, Marilyn Imrie, then a member of his department, saw Roderick as “exciting and also exacting. A wise and generous boss, who never expected anyone to do anything he couldn’t or wouldn’t know how to do himself… and an enormously skilful script executive”.

It was Marilyn who later prodded him into writing Golden Oldies – his first play for radio. Many would follow, penned as a freelance – but in a new environment. For in 1986 a cataclysmic shift of climate, personality and priorities, and internecine politicking within the corporation led to his return south.

His television work included Juliet Bravo and All Creatures Great and Small, while his interest in history and his friendship with David Collison led to his directing a dramatised documentary on Thomas Becket.

Not one to duck a challenge, he wrote what would be highly praised historical biographies of a quartet of noted Scots: John Knox, David Hume, Mary, Queen of Scots and Robert Adam.

All meticulously researched, full of insight, ready to cock a snook at received views and immensely readable: not a whiff of dull historical reconstruction, but the freshness, and immediacy, of his own voice.

Revelling in Edinburgh itself, its traditions and architecture, he was a regular theatre and concert-goer, with friends such as Mario Relich enjoying bracing conversations afterwards.

At another level there was demanded of Roderick, in life as in his writing, and as his wife Fiona was acutely aware, a rare doggedness and resilience. Her deep love and devotion was always present.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMy abiding memory of him is, first and foremost, as a gentleman: often, in Fiona’s presence, docile as a lamb… but imbued with courage and displaying – in adversity, and to the last – the heart of a lion.