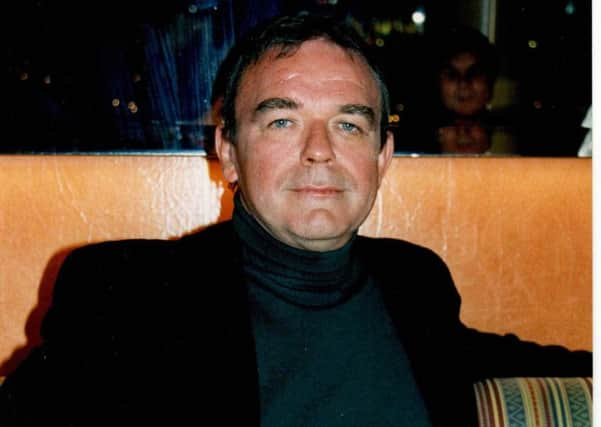

Appreciation: Joe Thomson, academic and Scottish Law Commissioner

Professor Joe Thomson, who has died just six days after his 70th birthday, was one of the leading legal scholars of his generation. He inspired hundreds of students with a unique style of lecturing and helped mould the law of the land during his nine-year tenure as a Scottish Law Commissioner. As towering as his academic achievements was the content of his character. An utterly classless man, this proud son of Campbeltown affected all he met with his natural grace and charm, which, allied to a turbo-charged joie de vivre, made him compelling company. Those close to him demonstrated an always requited love and devotion.

Joseph McGeachy Thomson was born in Campbeltown on the Kintyre peninsula. Campbeltonians have an acute sense of where they come from and the grounding provided by his childhood helped mould the values of the young Joseph, imbuing him with a sense that you should work hard to get on, celebrate success, but never allow status and good fortune to make you feel any better than those you grew up with. He loved his home town and his army of local friends were proud one of their own had become so distinguished.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEducated at Keil School in Dumbarton, he studied law at the University of Edinburgh, where he won the Lord President Cooper memorial prize for outstanding student. An academic career beckoned, first at the University of Birmingham and then, in 1974, at Kings College London. His happiest time as a university scholar came during his tenure as Head of the Law School at Strathclyde University, to which he was appointed in 1984. Seven years later he was appointed Regius Professor of Law at the University of Glasgow. The former Lord President Lord Brian Gill says: “The Glasgow chair carried great prestige and Joe occupied it with distinction.”

Joe Thomson had a love of the theatrical and his flirty conversational style gave an element of performance to the business of lecturing. An approachable man, he cared for his students well beyond the narrow confines of their academic welfare and he was genuinely loved by them. One recently wrote to him recalling the air of brilliance and irreverence he created. She wrote: “Cigarettes and gin and Lord Denning. What more could a young law student want?” He redefined the study of the law, having little time for the crusty aloofness of some academics and making it his mission to take the complex and explain it in everyday language. Lord Gill again: “This period of Joe’s academic life produced the best of him as a legal scholar.” His textbooks are a model of clarity without compromising thoroughness and generations of students still devour his published works: Family Law (1987), Delictual Liability (1994), Contract Law in Scotland (2000) and Scots Private Law (2006). Co-author Professor Hector MacQueen adds: “Joe pursued a law that was clear, coherent and certain in its detail as well as in its principles.”

The Eighties and Nineties saw his career soar and allowed him to indulge some of his great passions. He had a sensitive and adoring palate for good food and an even keener sense of which fine wines should accompany a meal.

He loved the arts, particularly opera, and had a good eye for paintings from artists straddling a multitude of styles. He would often combine gastronomy with artistic pursuits in some of the great cities of the world. He found something almost spiritual in the ability of words and music and art to refresh the soul. Friend Liz 0’Connor recalls: “We would often go to Italy to look at paintings. Joe always insisted on looking at one masterpiece before lunch. The gallery was always situated near a Michelin star restaurant.” He was, however, just as happy to bin high living and enjoy a DVD with a large glass of Grouse.

In 2000 he was appointed a Scottish Law Commissioner. Five years later his term was renewed for another four years, at which point he resigned from Glasgow University. By this time the emphasis on the corporate nature of schools of learning sat uneasily with Joe’s fundamental belief that they were there essentially to broaden the horizons of those whom they should serve above all else, the students. As a Commissioner he published a number of papers on such issues as damages for psychiatric injury, land registration, damages for wrongful death and insurance contract law. Joe Thomson loved the law, it appealed to his innate belief in the rational, that at its best it could be a force for good, providing remedies to make society more just.

Joe Thomson had several gay relationships but he was never one for pigeonholing himself. For one, his love of people would never have allowed it. His private life was not in good shape when he met the most significant person in his life, Annie Cowell. An accountant, she was as unstuffy as Joe and they formed a formidable alliance aimed at celebrating the good things in life. On their rollercoaster of wining, dining, partying, vacationing, came their army of friends.

On his retirement, they moved to a beautiful house designed by Gillespie, Kidd and Coia at Low Askomil overlooking Campbeltown bay. The ultimate party house, it became Joe and Annie’s sanctuary, but also their melting pot for entertaining. Everyone and anyone were on their guest list, from the Great and the Good to neighbours and friends. All were treated with the same generosity and courtesy.

As a couple they were utterly devoted to one another and complemented each other perfectly. Joe had an almost unchecked exuberance for everything he did. Annie brought order to ensure that he did not run away with himself. “Another drink, Joseph,” she would say. “That sounds good, Mrs Thomson.” He always looked at her with a wide smile and a boyishness bordering on innocence. It was the look that said he just loved her so much.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJoe Thomson had a deep religious faith. Unusually for an academic specialising in the rational, he didn’t engage in great intellectual discussions about Christianity. For him it gave a spiritual uplift and his relationship with the church was one he valued but one, for the most part, kept quite private. A few months ago he felt unwell while at Sunday worship. A cancer diagnosis soon followed. It crushed those close to him and yet he took the news without any hint of melodrama.

Joe Thomson’s essential humanity was in sharp evidence in his final weeks when I visited him in hospital. He laughed and joked with the doctors and nursing staff. When told of his treatment he asked: “Can I still drink gin and tonic?” He read voraciously, knowing that several lives would be too short to consume everything that there was to know. He held his spirits high in case Annie’s became too low. Her unconditional love served to strengthen his morale as he became physically weaker. With a characteristic twinkle of the eye, he said: “I love that dame, Bernard.”

On the day of his diagnosis we sat alone. “I’ve had a wonderful life,” he told me. That wonderful life touched everyone he ever met. Generations of lawyers owe him a debt of gratitude, not that he would have looked for it. Legislators have avoided pitfalls because of the rigour of his intellect. Everyone he counted a friend feels all the better simply for knowing him. You did indeed have a wonderful life, Joseph Thomson; the pleasure we all derived from it will be missed more than words can express.

Bernard Ponsonby