This Week’s Must Read: Malak Desert Child by Paul OGarra.

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

Young adult novels don’t always open readers’ minds, but Malak Desert Child is the exception to the rule and should be on every parent’s radar.

As every parent knows, in this age of internet streaming, social media, and computer games, it’s all too easy for a teenager to get distracted from any pursuit that will enrich and expand their minds.

We’d all much prefer our children to dive into a book rather than blast aliens online, but you only have to take a look at some of the most popular young adult titles to understand that many are just the literary equivalent of popcorn: filling but with no substance.

A good read shouldn’t only be for entertainment; it should come packaged with additional elements that make us think, and question. Books are a vital means of broadening horizons, and this is never more crucial than when dealing with younger readers, whose mental outlook is still in the process of being formed.

This is a matter that YA author Paul OGarra takes seriously, as you will see from his interview below. In writing his new novel, Malak Desert Child, he has made sure that it is not only a cracking adventure that teens will love but also a novel that will introduce them to important, contemporary real-world affairs.

YA author Paul OGarra.

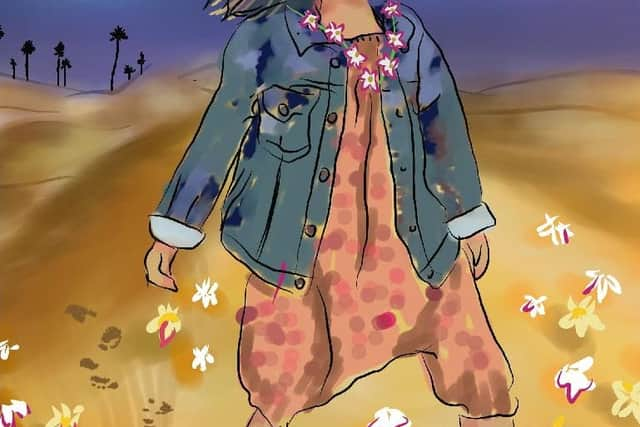

The story revolves around the eponymous Malak, a five-year-old girl who is both innocent and, in other ways, wise far beyond her years. When the novel opens, she is living in a small Moroccan coastal town. Though she has parents, they are desperately poor and are forced to live in a cave. Faced with these hardships, their daughter is, effectively, surviving as a street urchin. Yet though she is filthy and scruffy, the remarkable purity and foresight she possesses are plain to see on her grimy features:

“Her teeth were white and perfect, and her smile entirely unexpected in a face whose total lack of expression must have been the child’s only weapon against the evil and negligence which was happening around her, and which she instinctively knew was so, so wrong.”

Besides the financial hardships, Malak’s family environment is not happy. She, along with her mother, Tanirt, and older sister, Murdiyyah, live in fear of an abusive, alcoholic father. This situation is only compounded by the intolerance that Tanirt faces in the town over her Saharan background.

We are introduced to Malak, which means “angel” in Arabic, through the experiences of two characters that will have a major role in her life. The first, the mysterious, burned-out Pete, meets her at the home of a lady friend. He is immediately struck by her sweetness and, after offering her food, provides money for her to get some new clothing. The other is teacher Masuhun, also known as ‘Moon,’ who has been seeing her looking in at the fence of the school and is of the opinion that she would love to learn like other, better-off children if only given a chance.

“I think she’s living out the only version that’s open to her of going to school. It’s as if her only way to feel right, to feel like a child, is by doing what the happy, well-dressed children do: go to school. I bet if we were to offer her a choice between a boxful of food and a book, she’d go for the book. The irony is that she’d probably, actually, go for the food out of a sense of loyalty to her family.”

Having been touched by Malak’s plight, Pete and Moon, along with his friend Ruben, take it upon themselves to rescue the little girl and her family from their father, who is able to act with impunity because Moroccan law country dictates that he is “the king of the house and that’s it.”

So begins an epic quest to get them safely to Tanirt’s own people, a tribe in Western Sahara. It is no easy task as they are soon pursued by Moroccan forces, which in turn, are being directed by the nation’s leaders as a pretext to invading the disputed territory of the Sahrawi. The stakes have been raised, and what began as a mission of mercy may end with an all-out war.

Malak Desert Child is one of those novels that will remain with young readers long after they’ve finished the final chapter. It is written as a work of magical realism, where the fantastic and prosaic go side by side and has far greater resonance than the charged storyline alone.

True to OGarra’s goal of creating literature that helps inform young people of what is happening in the world around them, the novel introduces readers—in a simplified way, that they would readily understand—to the brutal realities of modern-day racism, nationalism, and neo-colonialism. While we in the UK may not necessarily be aware of the ongoing conflict between the Polisario Front and the Kingdom of Morocco, or of the controversial Berm (a guarded wall) that was erected by Morocco back in the 1970s to divide Western Sahara, this doesn’t matter as the issue is conveyed so effectively by the author. In his hands, it is boiled down to a battle of good vs. evil, of oppressor and oppressed, and the platform from which to launch valid criticisms of the wider political landscape, where exploitation is, sadly, rife. Take this observation from Pete, for instance:

“He awoke to the sounds of children playing outside in the alleys. He thought of how people, human beings, could make wars on each other when they knew children were playing in the same street or town square, where they dropped their targeted destruction.”

Or this comment by Tanirt about the plight of her own people against the might of Morocco in a discussion concerning another nation ripped apart by greed and prejudice, Syria: “Syria was a normal country with normal people taking their children to school, and now it’s being destroyed, they’ve assassinated thousands of children, next year it could be these.”

Without spoiling anything, Malak represents an alternative, non-aggressive path, and her instinctual wisdom, or perhaps faith, shines out like a beacon to all the jaded adults she encounters along her journey, prompting something of a spiritual enlightenment within them.

Protesters carrying Polisario flags gather in front of the Western Sahara Berm, erected by Morocco. Having travelled extensively across Morocco and Western Sahara, author Paul OGarra uses Malak Desert Child to make young readers aware of this international political situation.

As well as opening readers’ eyes to the hidden truth of the evil of modern-day colonialism, perpetrated in the pursuit of power and wealth (in this case, through control of a land “rich in oil, gas, and phosphates”), Malak Desert Child also provides young readers with spiritual and moral guidance. This is not based on any particular faith but is, to a greater extent, constructed on basic human rights that parents would wish their children to use as a template for their actions.

The other major thematic drive of the novel is to question the young’s dependency on technology. The simple yet noble lives of the tribes living in the desert, unadulterated with smartphones and the like, is emphasised. To them, and by extension, the author, a social network is a group of friends you meet with rather than a sterile, virtual world. Most parents, no doubt, would agree wholeheartedly with this sentiment.

More than anything, however, Malak Desert Child is a beautiful book and marks Paul OGarra as an exciting new YA author to watch out for. He has a strong command of evocative and vivid prose that sets the scene and creates three-dimensional characters that readers will care for.

For all these reasons, OGarra’s thought-provoking novel is highly recommended. It’s not your typical YA read and should be praised for its aim of highlighting real-world issues and providing sound instruction to the next generation.

Malak Desert Child by Paul OGarra is available now on Amazon in print and eBook editions, priced £12.32 and £4.69 respectively. Visit www.paul-ogarra.com

Meet the Author: Paul OGarra

YA author Paul OGarra has travelled the world on a mission to learn about other people and cultures. He now shares those eye-opening experiences in his writing for the benefit of young readers.

Now approaching his 70th year, Paul OGarra has travelled widely, savouring the experiences to be found in an immersion in other cultures. He was born in Gibraltar to a Gibraltarian mother and British father, a headmaster who made sure his three siblings grew up with a love of reading.

“Childhood was spent roaming across the Up South Rosia and Europa point areas of Gibraltar,” he recalls, “engaging in childish games and adventures, reading extensively books such as Enid Blyton’s adventure series— the ‘Famous Five’ and ’The Secret Seven,’— Swallows and Amazons and the ‘Gorbals Die-Hards.’ Saturday mornings were a day for delving and searching through the shelves of the old Garrison library to discover new horizons, characters, and stories. The journey of discovery that had begun with Babar the Elephant eventually began to grow richer as the classics were devoured.”

After receiving his education, Paul travelled on a steamer from Tangiers to Southampton with a friend who was shipping Moroccan leather goods to the UK. After working for a time in London, he left the UK to “discover his roots” in Malta and this was followed by other

enriching adventures. For a time, he alternated working as a tour guide in Morocco with recovering broken-down rented cars in the Sahara desert and acting as a tour guide of southern Spain, where he would eventually settle. He then found himself running a flamenco club on the Costa del Sol, “In the days when the Costa was still a new and exciting place to visit.”

He married and enjoyed an adventure of another kind—raising three daughters—while setting up and running estate agencies in Spain and the UK. His wanderlust never deserted him, however, and once his daughters were older, he set off travelling again, taking in the Middle and the Far East, the Philippines and Russia. He studied the Russian language in St. Petersburg and then travelled to the Ukraine and all over Russia, including the Republic of Udmurtia, Kazan, Siberia, Nizhny Novgorod and the South Volga, absorbing himself in Russian art and literature as he went.

In his fifties, Paul’s travels were curtailed with two battles with cancer that cost him a kidney and half of his lungs. Further health problems followed, with Paul suffering strokes in both eyes, leaving him with partial sight in one eye. Happily, he recovered full vision in his left eye, which he attributes to “swimming and praying,” and continues to be in remission for cancer. His treatment was finalized and he was declared cured in May 2020.

His illnesses, however, only enhanced his lust for life and deepened his resolve to make the most of his time. He travelled to Prague to study filmmaking, making several shorts. It was while studying that he recognised that his calling lay more in writing, and his first novel, The Boy Who Sailed to Spain, duly followed, being independently published in 2015. The politically-aware themes it explored, namely the ever growing decadence of an over-technologised West, were continued and expanded, touching upon slavery today, modern-day colonialism and the rape of the Third World by the West, in his follow-up, Malak Desert Child. He says that he writes specifically for a young adult audience, as a way of trying to extend their political and social horizons.

He is now based in the coastal resort of Fuengirola, where he divides his time writing, swimming (several kilometers per day, “come rain or shine”), and sharing his joy of reading with local families.

Exclusive Q&A with Paul OGarra

We speak to YA author Paul OGarra about his love of reading, views on contemporary fiction for young adults, and his aims and hopes with his latest novel…

Paul OGarra has a YouTube channel, ‘Paul Ogarra book readers review’on which he shares his favourite reads.

Q. What were your favourite books growing up, and what did they teach you?

A. Good grief! There are so many. I come from a family of four children, and we all had a taste for Enid Blyton, and although my father forbade us to read her, he finally gave up, and we enjoyed The Secret Seven, The Famous Five, the adventure books, and countless others. You need to realise that we devoured books while growing up as there was no television, just the street, school, and books. I then progressed to people like John Buchan with his detective books, and another series by him about a bunch of street kids who were adopted by a Glasgow butcher: the “Gorbals Die-Hards.” They had all sorts of adventures across Europe. And then, in no particular order, the works of Orwell, Huxley, Kipling, Dickens, Shakespeare, Stevenson, Swift, Twain and so many others.

In terms of my favourite books, now and again, something stuck, and even today, still lurks in the back of my imagination. I suppose the The Gorbals Die-Hards’ adventures, particularly in Huntingtower, will be with me always; God bless their souls. To Kill a Mockingbird is another favourite. I loved Scout and wanted to have a friend like her brother, Jed. I relished Pride and Prejudice, with Darcy’s visits and the drawing room conversations over tea. What did I learn? To read, for starters, to sit and concentrate on ever more complex and interwoven plots. I became aware of ideas, what they were, and how to express them, of history and geography, of God and religion and all the other religions and cultures and what they meant. I learned of the true nature of my own identity, as a child: about who I was; who I was in relation to others; and became aware of my own sexual identity, which I never questioned as there was no reason or need to do so—sex had not yet become so important in those days. My siblings and I developed an innate knowledge of things beyond our years through reading. I remember other parents asking my parent´s permission for their children to come and play with us, hoping our aura would somehow rub off on them, so the kids once told us. It was everything we learnt from books: how to live, and how to die, and to have impeccable manners and all the in-between.

Q. What do you think is lacking in today’s fiction for children and young adults compared to the literary classics?

A. I don’t believe you need to look that far to spot the difference. Go on to any YA site and look out for the genre they are pushing, and what authors are writing for this audience because they are being pushed there. I think children, as they grow up, develop the need to have a range of role models upon whom they can base their own experience. These are varied and change as they grow and can come from literature or even music. I, for instance,

remember that I was very affected by the Cat Stevens song, Hard Headed Woman. All my life, I looked for the ‘hard-headed woman.’ Eventually, she found me.

Today’s young generation has Harry Potter and his occult world, the occult being something that was banned in my childhood. We had Caligula in To Kill a Mockingbird, a small-town lawyer willing to be beaten up to defend his black client, at a time when racism and evil still roamed the back lanes of Alabama. It was more confusing to read and try to understand books such as 1984, Animal Farm, Island, Cannery Row, Anne Frank’s Diary, the works of Hermann Hesse, and Charles Dickens. They matured us and provided an understanding of what was right and what was wrong. And then there were Stevenson, Dumas, the dreaming Mr. Barrie, and Peter Pan. And Dahl, and Verne, and Chaim Potok, and Varnia. And Hemingway and Fitzgerald, and even Mr. Faulkner, whom I cherish to this day.

Q. What was your inspiration for Malak Desert Child?

A. My inspiration came from people I had met over the years, and it also was in part a way of giving thanks to Muslim friends who, when I came out of hospital following surgery for lung cancer, were the only friends who gave me the love and attention I needed. It was a bad time for Muslims and many minorities, and I tried to contribute my grain of rice to create a bridge of love and understanding between peoples, religions, and cultures.

Q. What do you hope young readers get out of your books?

A. I hope they will understand and derive a direction so that with the combined efforts of many like-minded folk, soon, we may see the disappearance of the tower of Babel that humanity has constructed with our new technologies and so-called ‘social networks.’ I hope they may again learn to live a life beautiful and free from the unkind and insidious manipulation which is foisted on many, and grow up to become the wonderful adults they would otherwise be destined to become.

Q. What motivated you to become an author?

A. Stories and poems. I´ve always written, and on second reading thrown it away. That was until one day, my youngest daughter said,” Papa, stop it! Keep it. Keep it all. Throw nothing away; it’s part of you.” And so I became an author, and I pass on that message today to any person with an inkling to write: “Don’t wait. Write it down. Throw nothing away, and work at it—there are always people to correct it, and publish when you can. Remember, it’s your way of communicating with others.

In becoming an author, I was also saying ‘thank you’ to my creator, who truly inspired me by letting me live, and see, and walk. My doctors often told me that miracles surrounded me and that the Lord was probably leading me by the hand. They said it light-heartedly but I knew it was what was truly happening. My illnesses began when I was 50, and now I am 68

(nearly, in May), strong as an ox with one kidney and half of each lung, and two fifths of my vision remaining.

Q. What is the most rewarding element of writing for younger readers, and the most challenging?

A. Well, I like young people. They are fresh, appreciative, quick to understand what you are saying, and they are what you see, no unaccounted for luggage. The other thing is that young people (and dogs, as well) normally like me.

Young people, if they get a chance to read and enjoy what I write, will place on my shoulders a heavy weight of conscience to continue in a vein that is sincere, pure, and always to their benefit.

Q. There is a spiritual dimension that underpins your novels. What are your own beliefs, and why do you think it is important that children receive spiritual guidance?

A. I was brought up as a strict Roman Catholic and wanted to be a priest when I was young; in fact, my cousin is a monsignor today. But having lived my life and read extensively, travelled, and met people from different cultures, today I consider myself a religious eclectic if such a thing were possible.

I am a child of God, I love God, and God is there for us all. I regard all religions as being roads to the Lord and I have worshipped with Catholics, Muslims, Christians of various denominations, Jews, Sikhs and Hindus. Friends accuse me of being unfaithful to my intellectual obligations. They talk to me of issues like, for example, the divinity of Christ, something that is disputed even within Christianity itself. And I say, “I don’t want to go into theologies and details. I accept everything they all say even if creeds overlap with other creeds. Just love and give and help and try to lead a good life. And perhaps for a day or a week now and then, try to imitate Christ to the letter.”

Q. You have travelled the world. What are your favourite countries and cultures?

A. My favourite people are the British, and that’s not smoke blowing, having done business with and experienced so many different cultures. It´s the ‘spade is a spade’ attitude that I like, along with the common sense, the good manners, humility and quiet pride. Many in Britain may decry this but I´ve lived it. OK, they´re not perfect, and you get some real characters amongst them, but have a look at what else is out there and you´ll soon set sail for Blighty again.

My favourite country as a traveller is Russia. I love Russia. It’s so passionate and interesting and full of culture and special things like white nights. The men and boys are very boyish and the girls beautiful. My favourites are the babushkas and diets (grandmothers and grandfathers). There´s so much to tell that can’t possibly fit within an interview but I’d like, at least, to share a little anecdote from my days when I was studying Russian in St.

Petersburg, just after Glastnost, at a small school named Educacentre, at Sinopskaya Nabrishnaya.

It was my first day, and I was late. I rushed into the underground through the crowds looking for a sign pointing to the gate for “SINOPSKAYA NABRISHNAYA,” but to my dismay, it was all in Cyrillics. Despair! The young kids all around me smiled and shrugged; they didn’t understand me. Then three babushkas (grandmas) grabbed me. I explained, they understood the words “Sinopskaya Nabrishnaya,” and they rushed me to a door gabbling away. Too late, alas. The train had gone. They pointed to the exit and said “taxi” so I rushed back to the street. Nevsky Prospect was packed. I stood uselessly by the side of the busy eight-lane carriageway and waved my arms in the air. Suddenly a big black, battered Volga car screeched to a stop. The ancient, rugged and enormous driver looked at me and said, “Shto” (“What?”). The car was packed with young girls presumably on their way to work. They were talking and laughing and giggling loudly. It was a madhouse. I said,” Sinopskaya Nabrishnaya,” and the driver replied, “Doma?”. I had no idea what ‘doma’ meant, so my face must have fallen. He said ”dvai” and waved a big arm to me to enter. The girls opened the door and I fell in amongst legs and laughing faces. They managed to squeeze me in amongst them and we shot off across the four lanes of the prospect and the hooting blaring traffic. We started dropping girls off one by one and they all, as they left, brushed my arm with a friendly squeeze as if to say ‘hi,’ or “Ochin Priatna” (“How do you do”). I was worried as it was only me now. Suddenly, the driver stopped. I looked at him, and he said, “ Academia.” Then I saw the sign, “Educacentre.” Against the odds, he had brought me right to the door. I grabbed my roubles and gave them to him but he pushed my hand away laughing, “Niet, niet. Dvai” (“ No, no. Let’s go).

Q. What do you think are the three biggest challenges in the world today?

A. Surely, in this day and age, it should be feasible for people and nations to reasonably sort everything out so that we have a true perspective and are able to mould a positive future for the planet. It’s not just the world leaders or the mysterious ‘mega-people’ behind the scenes. It’s everyone. They’re all at cross purposes.

But there is hope. Take Greta Thunberg, the Swedish global warming girl. Well, to my mind, her mission is quite defined. It is a switch to alternative energies. However, she seems to have become a bone of contention with people running around saying all sorts. I say, stand behind her. I don’t care if she is backing one group or another. Alternative energy and cleaning up the world can only be good things. So she may irritate some people, but I DO NOT CARE. Just let us stand behind her.

If I were to list the three biggest challenges, then they would be:

Get rid of the babelCommunicate effectively, at any cost, to anyoneSort the world out, as, it can be done, where there´s a will

Q. What would you do if Malak Desert Child became an international bestseller?

A. Who knows? For one thing, it would spur me on with my next book. You see, Malak is actually the second book in my series, following The Boy Who Sailed to Spain, but so far, it’s the best. So the third book is slowly cooking.

But most of all I would plant many, many trees. We would live in the Sahara and recover the deserts, using new technologies and bring back life to this dead part of the world. Children and young people would come from every country in the world to help us in our task. Streams and rivers would be reborn, and our fields of flowers would stretch for as far as the eye could see for thousands of kilometres, and our forests would grow and bring happiness. The deserts of Almeria in Spain are being recovered even as I write, and in Belo Horizonte in Brazil, an ex-reporter and his wife, sick of what they had witnessed in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war, returned to Brazil to plant an incredible forest for millions of kilometres.

And I might fall in love and get married.