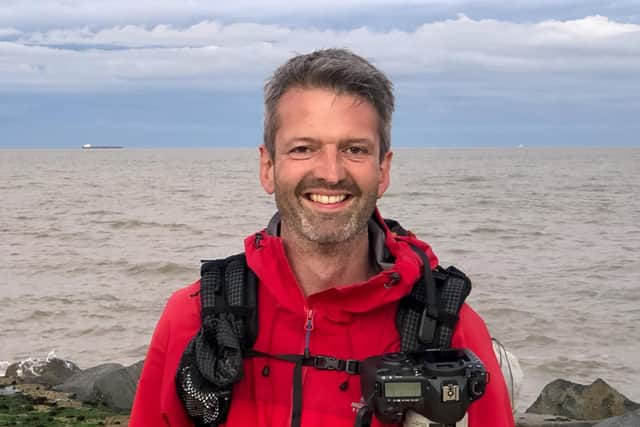

The man who walked and photographed the entire UK coastline, Quintin Lake talks about The Perimeter

The result is 179,222 photos of his journey, The Perimeter, a photobook, prints and forthcoming exhibition in Glasgow.

If that seems a lot of pictures, it’s not for Lake, a self-employed professional photographer who funded The Perimeter photography project by doing it in sections over five years, starting in London in 2015 and walking clockwise, and returning home to his family to edit, print and sell the images before setting out on the next leg, finishing the entire route back in London in September 2020..

After training as an architect Lake became an architectural photographer to pay the bills, saving up to go on expeditions abroad to photograph landscapes. It was after joining an Anglo Scottish mountaineering expedition to Greenland, when his abstract photographs of ice caps won a travel photographer of the year competition that he started producing landscape photos as a way to earn money.

Now it’s complete he faces the even harder task of turning the stunning images he took into a book, entitled The Perimeter and planning for the first public exhibition of the work at Sogo Arts gallery in Glasgow next year.

It’s the right time to speak to Lake, who is back at home with his wife, artist Mila Furstova and children aged six and eight in Cheltenham in Gloucestershire, now that we’re seeing light at the end of the tunnel in terms of travel restrictions. It’s tempting to dream about striding out in his footsteps, especially when he describes the Scottish leg of his Perimeter project.

“Scotland was my favourite part of the journey, especially the week in the Rough Bounds of Knoydart,” he says, admitting when he reached the road to the Cape Wrath lighthouse he fell on his knees and kissed the ground.

“Because that was so difficult, the north west. The views, and it was so difficult as well, that added to the intense feeling of it. Often it was like mountaineering because it’s so steep on the shoreline and there weren’t any paths, and I met some incredible people going through it.”

In the process of editing his photographs for prints to sell, exhibit and then turn into The Perimeter photobook, he’s winnowed the 179,000 down to 1,000, with the criteria being anything beautiful, interesting or something he hasn’t seen before. As it turns out half of the 1,000 are of Scotland.

“The Scottish light is more golden and you get more colour range than the rest of the island for sure, especially further north. There you get the ‘simmer din’ and the sense that it never really gets dark. Plus there’s a moisture in the air and a mist that adds to the feeling. You don’t get that reddy pink magenta that you get on the west coast that intense anywhere else,” he says.

Walking 12-25 miles a day depending on the going, he camped in a one man tent and bothied in wilder parts, staying in B&Bs in urban areas: Scotland constituted much of the former. Carrying 20kilos of equipment - six kilograms of photography gear (a camera, two lenses, a tripod, a drone and enough batteries for five days power), a tent, a sleeping bag, a stove, one spare set of clothing and one ration pack of food per day, trekking poles and an iridium satellite communicator to message home when out of mobile reach - he’d stay in a hostel or B&B every five days to recharge and clean his kit, sending himself dried food in packages ahead along the route.

“I need quite a few thousand calories a day and it has to be nutritious and light so I sent it to B&B and hostels or took to twitter for help and people would take a package. I got a lot of help, especially in Scotland.”

But why undertake such a journey in the first place? As Lake wrote on his website before starting:

“I hope to learn more about our mysterious island nation and I can't think of anywhere else where each footstep leads to such different surprises, beauty and strangeness” and he quoted Oscar Wilde: It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible" Oscar Wilde

For Lake the journey was to find photographic inspiration, a spiritual and cultural experience, as well as having the physical aspect of walking through the landscape, something it turns out we can all relate to.

“That’s what’s beautiful about the British people. When you tell them you’re walking around the entire coastline of Britain, you never get anyone saying ‘that’s crazy why are you doing that?’

They just go ‘oh that’s brilliant’ and most say ‘I’d love to do that’. I’m always surprised by that. Some say I’d love to be able to AFFORD to do that’, which can be galling after I’ve been in the cold and wet for five days with no support crew, no vehicle, and can only afford a B&B one night in five,” he laughs.

Growing up in the south of England, Lake, now 45, had hiked a lot from childhood, especially in Scotland, for which his half Canadian mother had a love.

“I walked from John O’Groats to Glasgow with my mum when I was ten, then when I was old enough to go myself. I’d go with a tent and walked from Cape Wrath to Inverness when I was 18, then from Lands’ End to John O’Groats when I was 20.”

But no matter how experienced, and how much planning Lake did, he wasn’t prepared for what Scotland had in store.

“When I started I really had no idea how intense and different it would be in Scotland. It really was a journey of two halves. In most of England there were regular shops and facilities but in Scotland it was often up to five days where I wouldn’t see a soul and I was totally self-sufficient with a tent and dehydrated food. It was a totally different experience to the other two countries.”

Because Lake was walking along the coast, there were few footpaths to follow as he made his way from south west, up round the north coast then south down the east coast.

Now that we’re all desperate to get back out into the great outdoors, inspired by the likes of Lake, the concern is that we’ll go on the rampage en masse through our beauty spots, trashing what it is that makes our country so beautiful in the first place. How does Lake see us behaving post lockdown? Responsibly, or will it be a totally rammy?

“It’ll be really fascinating to see,” he says. “Whether this is a new dawn of respect for the outdoors and being outdoors or whether people will go straight back to the old ways, I really don’t know,” he says.

“My ethos about camping is to leave the place cleaner than I found it. It’s not about just having a neutral impact but trying to have a positive impact. Especially on the coastline there’s always a few bits of plastic around.

His advice?

Don’t light fires anywhere. The only place it's OK to have a campfire is below the tide line so the sea washes all the remains away. And be prepared for going to the toilet. Carry some kind of digging implement so that animals don’t dig the waste up - it’s disgusting by most of the roads where you get people stopping and toilet paper lying around the place - so be prepared with a trowel and biodegradable toilet paper rather than normal paper. I could go into more specifics but it’s probably too much,” he trails off.

Not at all, we need to know.

“Ok,” he laughs, “You need to dig a little hole six inches deep, do your business and stir the whole thing up with a stick then put the toilet paper in and it will biodegrade really quickly and animals won’t dig it all up and scatter it around.”

Now you know.

“And obviously take your own litter away with you. If we want to continue the amazing access rights that we’ve got and people not viewing backpackers and campers negatively then we need to act as a positive influence.”

Because his walk was pre lockdown it was rare for him to meet anyone on the Scottish leg.

“Every day there was something beautiful and spectacular and I was always struck that no one was out there enjoying it. The general pattern is you get a car park and then half to one kilometres away you get dog walkers and on the more known trails you’ll get day walkers, but backpackers doing multi day journeys, I didn’t see that at all. Most of the other hikers I met were doing the Cape Wrath trail and I met them in Sourlies Bothy on the edge of Knoydart,

“There’s an Ayrshire coast path and round the Clyde, but once you leave that, most of the route is unmarked. Most of north west Scotland there was no path at all so it was wild route finding. I do enjoy the aspect of coming to a headland and seeing pristine landscape ahead and figuring out your own way across it. The Aberdeenshire coast path was the first decent path I found, and because I was following the coast, there would be settlements over the hill, but because I wasn’t on the roads I wouldn’t see them.”

Sleeping alone on the more remote reaches of the Scottish coast in the depths of winter isn’t for everyone but Lake didn’t mind the isolation.

“I’m not lonely. I’ve certainly been scared, in my one man tent though. There have been a few nights where I’ve thought this is the night where it’s going to get crushed. I had all my kit in a bag ready to evacuate when the storm flattened the tent, but it managed to keep standing. That’s why I like the small one because it gets warmer quicker and there’s less resistance to the wind.

“I’m certainly very grateful to see people when I do see them, and I think they are me. In the wilds you don't meet many, apart from rural farmers. I’d find sometimes I’d be talking too much and realise this person wants to get on with what they’re doing, but it was because I hadn’t seen anyone for a number of days.”

There’s no doubt Covid has made us appreciate that getting outdoors and walking is good for health reasons, both physical and mental and Lake would urge us to get out and walk when we can.

“No matter how burdened you are with concerns at the beginning of the day if you walk all day they seem to evaporate, especially if you’ve used your own body to cover distance from A to B. It’s exaggerated if you have the satisfaction of carrying your own food and bed on your back. It’s a really empowering feeling for me. I found lockdown a lot harder than doing this walk so I make sure I walk every day.There’s a lot of healing in it.”

“I've observed over the years how much happier I am doing it. When those trials and tribulations of life come, I look forward to it as a chance to kind of reboot or reset my mind and remind myself what's important,” he says.

The sheer physicality of walking, especially in natural landscapes, has benefits according to Lake.

“It's so rhythmical, the act of walking itself, and a coastal journey compounds that because you're working with the rhythm of the tide and the rhythm of the moon. And somehow for me, it's very important that it's for quite a number of days because for the first couple my back hurts and my feet are quite uncomfortable, but after a few days your body attunes to it and you get into this kind of flow state, and you're much more attuned to the patterns of nature. And all the dramatic pictures are after I’ve been soaked or am about to be soaked,” he laughs.

Walking into a view, rural or modern also increases his ability to spot a composition.

“Whether it’s a power station or something modern, which I also enjoy, it seems clearer if I’ve walked to it. I literally would not be able to take these pictures if I drove to these sites. It's the calm that comes from deep inside your soul from a long walk and it's easier to see things as they are.“

As for where to walk post-lockdown, Lake advises steering clear of the obvious tourist hotspots that suffer from overtourism, but isn’t prescriptive about listicles of locations. His advice?

“Throw a dart at the map and pick something at random. We’ve all heard of the spectacular iconic locations in Scotland but really there are no duds. There are not bits that won’t be a good experience, based on my experience. A bit of more tangible advice is that all the peninsulas are special because they don’t lead anywhere. To go to Kintyre or Ardnamurchan you need to be making the journey specially, or the Mull of Galloway, which is often overlooked, I thought the whole of Dumfries and Galloway was really magical.”.

“Pick some of the less charted parts, maybe a headland or a village and work out a way to join them up and you’ll find beautiful, interesting things that aren’t on a tourist website and you’ll have it to yourself.”

As for setbacks, Lake suffered a split tendon and shin splints, requiring him to stop for two months each, lockdown of five months, plus the menace of midges and ticks.

“There’s a lot of Lyme Disease up on the North West and they’re hard to remove with only a tiny mirror in a tent, so I missed one and had to have antibiotics.”

For midges he recommends Smidge. “Great stuff. Or Avon Skin So Soft, but that’s a bit greasy if you’re working a camera. A head net is good, green so you can see them better, and that hour either side of dusk is hell so try to keep moving then. Camp on high ground and if it’s windy that’s good - more than ten kilometers an hour and they can’t fly. A lot of my shots I had midges inside the camera and I did a lot of photoshopping them out,” he laughs.

With the journey behind him and the book an exhibition ahead, what does Lake feel now when he looks at his photographs and reflects on his coastal walk.

“What I’m absolutely certain is there’s not a better thing I could have done with those five years of my life, which is a revelation because when I started, it was an experiment, it was an adventure. I didn’t know quite what would happen, but having done it I think it's the best thing I could have done with my life.”

“I felt human with every fibre of my body to be exploring creatively and physically, and there’s nothing more fulfilling than that. Each day you don’t quite know what’s going to happen. It’s an adventure, but you have a purpose because you’re on a journey, and an aim which is fulfilling, so those two things intertwined is a recipe for happiness, at least for me.”

'See more of Quintin Lake’s photos and buy prints at theperimeter.uk

Quintin Lake’s Perimeter photography exhibition will be at Sogo Arts gallery, Glasgow

https://sogoarts.com next spring.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.