Travel: Outer Mongolia

When we got back to the city, we all met again for a meal. Someone had a map of the country, and our guide drew where we’d been on it.

“Is that it?” I asked, disappointed. “Is that all we’ve seen?”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the table in front of me, where the map of Outer Mongolia was spread out, it didn’t look like much: a blue Biro mark that headed to the right of Ulaanbaatar for half an inch, then moved north for the same distance, and swung back to the city again.

Below the blue circle, the Gobi desert: untouched, unseen. Far above it, Lake Baikal, over the border in Siberia, which those girls at the ger camp had raved about and wanted to go back to: let’s face it, I’ll probably never get there now. The same goes for Hovd, a thousand kilometres to the west, where our guide Tudevee came from, where he told us he’ll be carried up to some peak the day after he dies and left to the vultures. I’ll never see those mountains either. It was

meant to be a celebratory meal, but I was starting to feel maudlin.

“It’s a big country,” consoled Harry, a young Englishman who’d fixed up our holiday with the nomads of Outer Mongolia. “You can’t see everything in a week.”

I had arrived in Ulaanbaatar almost deliberately ignorant about the country. Yes, I knew Outer Mongolia was big: the world’s second biggest landlocked country, the size of eight Frances, and with just over 2 million people living there, one of the least populated. But staying with nomads would be strange enough, I reckoned, without trying to find out everything I could about them. I’d take them as I found them, and they’d have to do the same with me. And that turned out to be a good move. Because that Biro’d blue circle on the map was the most weirdly magical journey I’ve ever been on.

Weird? OK, try this. You’re upstairs in the Scottish pub in Ulaanbaatar, drinking Chingghis lager, watching a small crowd of enthusiastic Mongolians Stripping the Willow and doing the Gay Gordons. A Scot setting up the country’s computerised tax system (how do nomads pay tax?) has taught them Scottish country dancing, and they love it. All of which is weird enough, but doesn’t compare with seeing the door open and a friend from Edinburgh walk into the room, at which point an already great night tips over into an unforgettable one.

You won’t want to stay long in Ulaanbaatar, though, and you shouldn’t. It’s a Mad Max sort of place: unfinished bypasses crazily crammed with manic traffic in a city surrounded by thousands of tents. This time of the year, it’s the world’s coldest capital, with temperatures plunging to minus 40C.

It is also so polluted that breathing its air for a day is reckoned to be the equivalent of smoking four packs of cigarettes. Official figures show that one in ten deaths are caused by pollution, unofficial estimates push that figure up to one in five. Traffic is atrocious, buildings from the Soviet era charmlessly concrete, seemingly unplanned and barely insulated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA wild eastern variety of capitalism doesn’t seem to be doing the country any favours either: instead of hospitals and universities, all the Mongolians seem to be getting in exchange for their lucrative mineral rights are ludicrous projects like a distant airport and plans for an enormous Buddha bigger than the Statue of Liberty in the middle of an unappealing development sponsored by the hated Chinese. Corruption is in the air almost as clearly as pollution.

Why then do I persist in thinking that Outer Mongolia is a place of wonder? Because when you drive even just ten miles out of Ulaanbaatar, out on to the wide open steppe, you’re in a different country.

How different? Try this. You’re staying with a family of nomads in a beautiful river valley which, apart from the absence of fences, walls,

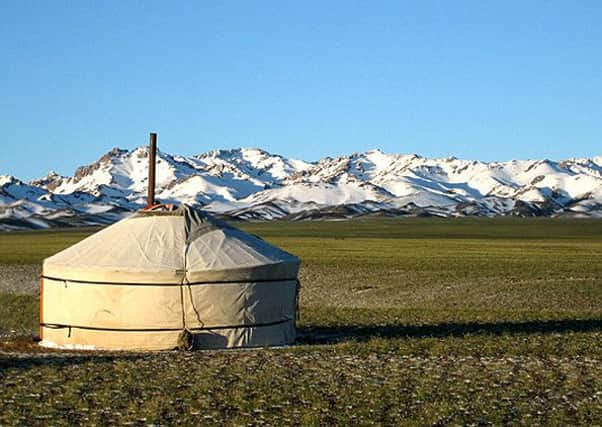

roads or any sign of human habitation, could almost be the Scottish Borders. You’ve got your own ger, the brilliantly economical circular felt-covered tents which only take 20 minutes to put up and which are unchanged since Ghenghis’s day. No electricity, no toilets, but there’s a stove in middle to burn larch logs from the copse across the river (or, for less heat, birch or dried animal dung).

Naraa and his wife Bujenlkham live with their three-year-old daughter in a ger 20 yards away. From the outside, it’s the same as mine, though inside, they have had a solar-powered television, which they mainly watch to pass the long winter nights because there’s just too much for a herdsman to do in the summer. Apart from that, we could be back in the Bronze Age. Life is hard, and the biting winds make Naraa and Bujenlkham both look older than their 33 years. It’s also

elemental in every sense: the only thing keeping the wolves from the sheep-pen door in the -40C darkness is Naraa’s attentiveness and horsemanship.

My stay was far too short and I don’t want to over-romanticise the nomadic life. All the same, I came back changed from meeting them. In the thousands of years of our civilisation, we can hardly imagine a country where land isn’t owned and where you are free to move your ger wherever or whenever you want. Maybe the taxman will get them one day, but they seem free enough to me.

So while they’re as friendly and as interested in strangers as people in remote communities everywhere, and while they are deeply hospitable to strangers in a way that we have mostly forgotten, they are not overawed by westerners. “You can’t have a laugh with them as easily,” explains Naraa. “They take us so seriously. If we said it was a thousand kilometres to the nearest garage, they’d just nod sympathetically.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEarlier, we’d stayed at a nomad camp by the Kherlen River, where the nomads had gathered for a mini-Naadam, the Mongolian equivalent to a Highland Games, celebrating the “three manly arts” of wrestling, archery and horseracing, as well as competing to tame wild horses and put up gers in the shortest time. The women had their own event - dried animal s**t-collecting.

In the evening, everyone put on their finest robes and sang songs about brave men, horses and their love for their mothers. The children danced, and in the back of the room, their mothers did what stage mothers do everywhere, drawing semicircles under their faces so their children remember to smile.

I’d already heard the country’s finest throat singers singing chords (chords!) whose top notes flew off round the room like a bird, I’d already seen their finest dancers fling themselves around the stage re-enacting their oldest myths. But as I sat back and watched the children eagerly sing, even though their music was strange to me, I felt as though I half understood it. In this circle of warmth and light, two weeks from winter, I realised that this music and dance wasn’t just for tourists but for the nomads themselves, a celebration of hope and happiness.

They’re not my people, but I felt as proud of them as if they were. Which is another way of saying that they made me feel proud of being human. On the darkening steppe of Outer Mongolia, I felt a moment of transcendence, as though I’d had a brief glimpse of the best of us.

GETTING THERE AND WHERE TO STAY

David Robinson flew to Ulaanbaatar from Edinburgh with Turkish Airlines - all other routes involve one or more changes of airline. Turkish Airlines also provides free overnight accommodation in Istanbul if the flight involves a stopover or a free city tour. See www.turkishairlines.com

In Outer Mongolia, he was a guest of Panoramic Journeys, who specialise in tailor-made and group tours of

Outer Mongolia. A two-week Nomad Encounters holiday costs £2,740 excluding flights from UK. For that and other holidays there (and in Bhutan and Burma) see www.panoramicjourneys.com, or phone 01608 676821 or email [email protected].

For accommodation in Ulaanbaatar, the five-star Kempinski Hotel Khan Palace is at the top end of the range, and provides free mobile phones for the duration of your stay (www.kepminski.com), although the Edelweiss Hotel (www.edelweiss.mn) might suit those on a budget. A cultural tour of the city is a must - especially a visit to the theatre to catch an incredible performance of throat-singing and traditional song and dance (see www.juulchinworld.mn). The Modern Nomads restaurant chain in the city offer lighter versions of traditional Mongolian classics and are also recommended.